Egypt is a country with, as of April to June 2020, a 9.6 percent unemployment rate, a rise of 1.9 percent from the first quarter of the year. However, for veiled women (hijabis), who objectively constitute a majority of women in Egypt, employment is a different ballgame.

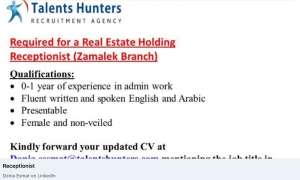

In the last decade in Egypt, there has been a trend of discrimination against hijabis in the job hiring process. Documented on social media, job listings have requested non-hijabis, hiring managers have directly told hijabis they would need to edit how conservative their hijab style is for the job, and others were asked to take it off completely.

In 2013, a customer at Spectra, a restaurant in Mokattam was in the bathroom when she discovered that hijabi employees at the restaurant are made to take off their veils during work hours and would put them back on after their shift. After the customer’s Facebook post went viral, a small movement began to Boycott the restaurant, but its reach was limited.

المذيعة دينا زكريا تعلن أنها ستقاطع مطاعم سبيكترا بسب تعنتهم ضد الحجاب ..

السلام عليكم و رحمة الله و بركاته

النهاردة…Posted by Boycott Spectra قاطع مطاعم سبكترا لإجبار العاملات على خلع الحجاب on Saturday, January 5, 2013

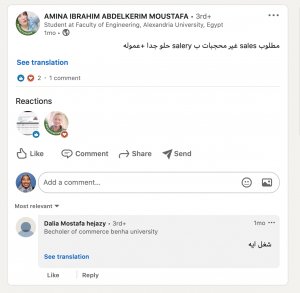

It’s not just the restaurant industry that has this type of discrimination, however, and while Egyptian Streets has found that this trend is more popular in customer-facing job roles, it is still prevalent in a variety of different job types as well. Another Facebook post went viral earlier this month; the post was by 29-year-old Nada Salah El-Din who is asking for a law to protect hijabis from being discriminated against in the workforce after multiple experiences she’s had of getting rejected from jobs that prefer non-hijabis.

بسم الله ..

موضوع محتاج قانون يحمي المحجبات عشان كفايه كده، بتعرض لنفس التنمر و السخافه و تضييع الوقت و الأستغلال ……

Posted by NaDa SaLah El-din on Saturday, January 2, 2021

Say It in the Listing

Egyptian Streets spoke to Salah El-Din, who was immediately keen on sharing that she has the experience and knowledge in her field of Human Resources (HR), as well as a degree in the same field, as many people reacted to her Facebook post, she says, claiming that the reason she was being rejected jobs was that she was unqualified.

“Since 2018, when I tried to settle in Egypt, I’ve seen four to eight job ads that explicitly state that either the preference is non-veiled women or directly only ask for non-veiled women. I never accepted it and I’ve previously expressed that, but, after these experiences, that (explicitly stating this preference) to me has become better, although I don’t accept it,” Salah El-Din tells Egyptian Streets.

Knowing that she wouldn’t be accepted from the start, she says, is better than going through the process without knowing.

“There were about four times where I left the interview confident that they will not call me back because of my hijab, whether directly or indirectly. For example, I was interviewing at a real estate agency and I was told by a former employee I knew that the company wanted non-veiled women, but no one there told me,” she adds.

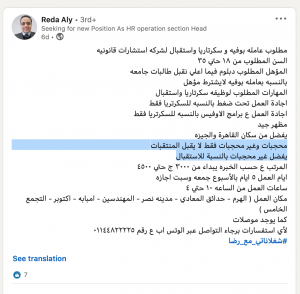

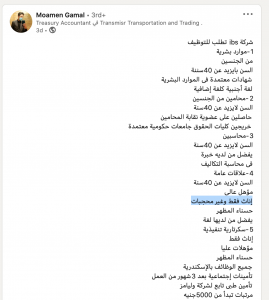

It is not uncommon, though, to have this “preference” in job listings, which can be considered an act of discrimination. From a quick LinkedIn search done by Egyptian Streets, several recent job postings from the last few months ask for non-hijabis as part of the qualifications of the job. Notably, some of these listings bring up further issues including objectification and commodification of women. Receptionist, secretary, baking, public relations, and sales roles tend to be the most popular fields where these preferences are common.

“Maintaining the Image” of the Back Office

Sarah Waleed* is an Economics graduate and a veiled woman. In late 2018, she sent her CV, which didn’t include a photo, to a large accounting and auditing firm job opening. She later got an email back, did a phone interview, and was invited for an in-person interview.

“If you’re looking for a job and you’re currently employed, it can be a little bit tricky to get time off but I was lucky enough that I was able to get time off for that day and I live in New Cairo, and the company was in October so it’s a huge way for me to go and I don’t own a car,” Waleed tells Egyptian Streets, “I took a SWVL, I put on my best suit, my fanciest designer bag, felt super confident and qualified, and I felt like this interview should be a breeze and I went.”

The technical and financial aspects of the interview went well for Waleed, but before dismissing her, her male interviewer told her that the position was going to entail some form of personal sacrifice on her behalf.

“I assumed that he’s talking about that because I’m switching industries and sectors, they can’t give me much in lieu of financial compensation. I also thought that because I live in New Cairo and the company is in the Smart Village area, that it’s going to be a long commute for me,” she adds.

Waleed was keen to proceed until the interviewer said it was the personal sacrifice had to do with that “the company has a certain image that it needs to present.”

“I told him that I didn’t understand- He wasn’t very blunt, he didn’t say “oh, it’s your hijab,” he said, “well, for example, your attire will have to be changed significantly.” And then he vaguely moved his hand around my head in a circular motion, kind of to say, “Oh, this thing that you’re wrapping your head with has to be changed in a significant way.”,” Waleed adds.

She thanked the interviewer and left, “I remember crying all the way from the SWVL ride from the company all the way back home, feeling the most heartbroken I ever felt, because I knew I was qualified and capable. I knew that I’m probably overqualified for the position that they had, one of the top graduates at my university, one of the top hires at my current employer, and yet, all of this is not enough because of certain prejudices that other people have.”

Later in early 2019, Waleed applied for a different position at a company with an exhaustive application process that included an online application, a shortlist interview, and a case study. She made it till the personal interview.

“I showed up, and one of the things that I quickly noticed was that none of the other applicants were hijabi. In the company, I only saw one or two but the way that they wear their hijab was very, shall we say, relaxed. Not that one is better than the other, but if the image of a hijabi comes to mind, that essentially wasn’t it. That was an observation that perhaps that was the only form of coverage that they tolerated at their company, and someone like me, who wears looser, more full-length hijab probably would not be welcomed.”

In the interview, once again, the technical portion of the interview went fine but then the interviewer reiterated the same words about the company’s image.

“In both companies I was not client-facing, so I have no idea what the image they want is or why the image is important. Since no one is going to see me, I’m a back-office analytics specialist, I am never going to be in marketing or sales, it’s just going to be me and my laptop and my Excel sheets,” Waleed adds.

Waleed left, having understood the routine, with newly minted anger to replace her previous disappointments.

At her current job for a quasi-public bank, Waleed wanted to try a new sector within the banking umbrella and applied for the job. The current Chairperson of the bank, she says, is a Muslim hijabi woman who wears a conservative hijab, and several heads of departments are also women who wear a conservative hijab.

“The person I went to interview for said it so explicitly to me that, if I took off my scarf, she will consider me for the position. I told her “You can’t say that to me. You can’t say that to me in this bank, in this department. You can’t say that to me when this is our current leadership.” That was the only time that I went to HR and told them that I have been met with some form of discrimination towards a particular job,” she says.

Waleed was told that HR spoke to the interviewer and said that she’s no longer allowed to do any more hiring and firing decisions. However, she doesn’t think that will be a particular deterrent to the issue, because many people still have the same idea, she says, especially when it comes to more client-facing positions; they still don’t want hijabis.

Who’s in Charge?

While the niqab (veil which covers the face) is a much more conservative religious dress, the discrimination Niqabis face is still similar to that of hijabis in the workplace, and it often depends on who’s doing the hiring and the firing.

Jannah Ahmed* was turned down a job in 2009 to be a reporter at a popular newspaper because of her niqab. When the Editor-In-Chief changed, the new editor gave her the job.

“The first editor did not explicitly tell me that but when the second one hired me she told me the conversation she had with the first one,” Ahmed tells Egyptian Streets.

While there are legal obstacles to hiring a Niqabi in an educational setting, she says, at the newspaper, there were no legal obstacles, and it was only about the editor’s personal issues and stereotypes with the niqab.

“Rather there are media and journalism laws about not discriminating because of religious dress,” she adds.

“Quick Question, Are You Veiled?”

In 2003, Rania Khalil had just graduated from university in Sharjah, UAE, and as an Egyptian, she wanted to experience living there and applied for a job vacancy via a friend. After email exchanges, Khalil had a telephone interview with the HR manager that went well, and arranged a meeting with the regional manager once she arrived in Cairo.

“I called once I arrived and we arranged for the interview and could hear the same enthusiasm in her voice. Just before I hung the phone up she said “Oh Rania, quick question, are you veiled?” I asked if that would make a difference and she said no, so I said well then, you find out when we meet,” she says. “I arrived at the interview and I could tell she was surprised to see me veiled. She said “Why did I think you were not veiled? Was the photo on your CV without your hijab?” I replied that I never had a photo on my CV.”

Khalil’s interview with the regional manager lasted for five mins, and on her way back home, the manager called her to say that she was not suitable for the role.

“I now live in the Netherlands, worked at an international oil and Gas company as an HR manager and I literally never heard a comment about my scarf,” she says.

Sherry El Fouly is not a hijabi but she still had an experience aligning with this trend when she was interviewed for a patient relations role at a health insurance company.

“During the interview, I was told that they don’t hire hijabis so if I am thinking of getting veiled then they won’t offer me the job. They also told me we don’t allow unnatural hair color, veils, or tattoos, and these things are worth firing over for or getting your application rejected for. I don’t think they would have called me if my CV picture wasn’t included and I was clearly not veiled,” El Fouly says.

Mariam Nesr* was 19 when she had to turn down a job for the same reason.

“It was not rejected as much as it was just hinted at and I was too young to understand how offensive it was a full-time job as a PR representative; meeting clients and contacting people. Apparently, they thought I was a great fit, now that I think back on it it’s probably because I was fairly good but malleable enough to be financially exploited,” she tells Egyptian Streets.

The company had two conditions for Nesr, one that had to do with her enrollment level at university, and the other was that she start wearing a shorter type of veil.

“I asked what was wrong with the veil and they said it looked too big, intimidating, and not presentable enough. I left and said I’d call back and then called and turned it down,” she adds.

Consistently a Concern

It isn’t just the application process, the hijab can be cause for mistreatment in the workplace for some women. Nada Youssef says she was once explicitly offended for her hijab during an internship.

“My employer kept asking me personal questions such as at what age I started wearing it, and if my mom wears it as well. Then he mockingly said he will force his three year old daughter to wear it. It made me really uncomfortable,” Youssef says.

Those who haven’t experienced it yet know others that have, inevitably limiting the ceiling of their professional lives.

“It could be demotivating at times that we find ourselves in an awkward and conflicting position between our identity and a job opportunity. It’s something always in the back of my mind that I fear will face in the future,” Salma Elziady tells Egyptian Streets.

Elziady is 20 years old and a hijabi, and while she has never directly experienced this type of discrimination, she worries that this will be something she faces eventually in the workforce.

“Regardless of their background, their education and social status, hijabis are always regarded as less than and inferior to their non hijabi counterparts. In general, not only in employment, society has attributed Hijabis with imprinted and attached negative stereotypes, but non-hijabis get praised from the get-go as intelligent, elegant, social, open-minded, and more attractive than hijabis. Thus, they’re perceived as more worthy of a vacant position,” she adds.

Where to Go From Here?

By many measures and standards, these acts of exclusion can be considered discriminatory or unlawful, but is there a way that significant change can occur to allow equal employment to all?

Nesr says that inclusion is a big part of the question, since there aren’t many hijabi presenters on television that represent the population. Salah El-Din asks something simpler, “Write in the job ad that they don’t want veiled women instead of us doing an interview call or face to face and wasting our time.”

On a more global level, she says, what should be enforced on companies and other institutions that prevent hijabis from entering should be a law enforcing that they can’t have any conditions on employment including race, appearance, age, height, etc, except for their qualification for the job. She adds that there should be an audit from the government that this is actually being enforced and implemented.

For now, what has worked on a smaller scale was a mere report to HR, as in Waleed’s case.

Discriminating against Egypt’s veiled women is in turn affecting a large majority of the women in Egypt, which may result in less female hires as a whole.

What Salah El-Din knows for sure is that if this culture of “racism” and preference exists, then the same society that created it is the one that will be able to reverse it over time, with policies and audits.

According to the Egyptian Labor Law Number 12 of 2003, the Equal Opportunity clause states that the law prohibits discrimination in wages on the basis of sex, origin, language, religion or creed.

*Some names were requested to be changed for privacy to prevent further hiring discrimination.

Comments (2)

[…] Morsi, N. (2021, February 1). Hijabis demand justice in the Egyptian workplace. Egyptian Streets. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://egyptianstreets.com/2021/01/31/hijabis-ask-for-justice-in-the-egyptian-workplace/ […]

[…] by NaDa SaLah El-din on Saturday, January 2, […]