‘Illness, disease, epidemic.’ These are the terms that are commonly, and incorrectly, associated with autism. To say that this neurodivergence is misunderstood in Egyptian society and beyond is an understatement, yet in recent years, many individuals have worked tirelessly to alter perceptions of it – and continue to make exceptional progress.

Autism is a lifelong, complex developmental condition characterised by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviours, speech and nonverbal communication. There are many types, and those with autism are commonly said to fall on a ‘spectrum’, and each person experiences a different set of strengths and challenges.

Some people with autism may struggle interpreting the nuances of social interaction or experience sensory intensity, including towards sound, light, temperature and smell, which can be perceived in extreme or unusual ways. Others may develop highly focused interests and be skilled in logical thinking and have particularly precise memory ability. Some may be able to live independently, only experiencing autism very mildly, while others need continual support from a young age.

Attitudes towards autism in Egypt have changed majorly over the past couple of decades, and no one has witnessed this shift quite like Dahlia Soliman, founder of the Egyptian Autistic Society, a non-profit organisation which supports people with autism, particularly children, and their families. Ever since her experience babysitting a child with Down’s syndrome at the age of eleven, she has been set on dedicating her time to working with children with special needs. Following her bachelor’s degree in Psychology from the University of New South Wales in Australia, and subsequent Master’s from the UK’s University of Birmingham which specialised in autism, she returned to Cairo to establish the society.

“Incorrect assumptions about autism existed more when we first started, in 1999. In the beginning, you would still see people who viewed [autistic people] as touched by spirits, but I think this has really gone down a lot,” Dahlia says.

“Compared to before, it’s much more acceptable – it’s no longer taboo to have a child with special needs.” she explains.

Much of this previous misunderstanding of what autism is in Egyptian society can be put down to a lack of awareness amongst the scientific community. In the Middle East and North Africa region, autism only became a field of interest in the late 1990s, and there is a notable lack of scientific publications on the subject from this region. The centre of much of the research dedicated to autism has taken place in affluent English-speaking nations, leading to the concerning belief that autism is less prevalent in ‘non-western’ cultures. This is something that Dahlia has witnessed first hand when the Egyptian Autistic Society was first established.

“70 to 80 percent of the cases that used to come to me were misdiagnosed, even by the biggest paediatricians, neurologists and psychiatrists. That was terrible, as they were being treated for different things, and receiving the wrong therapy,” Dahlia describes. According to her experience, these misdiagnoses included cerebral palsy and so-called ‘mental retardation’ – “things that just aren’t related to autism,” she explains.

Over the past twenty years, the gaps in scientific studies relating to the prevalence of autism in the Middle East and North Africa are slowly being filled. Interest in the field has grown particularly in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, which have produced the most research in recent years. Across this time period, progress has also been made on the ground, and the Egyptian Autistic Society has been a key player in driving awareness campaigns and supporting autistic individuals in varying ways. Dahlia is always keen to convey the fact that when supporting autistic children, early intervention is key.

“The more early intervention you can do, the better the prognosis, basically. We teach them basic things like potty training, how to eat alone, to recognise their parents, and speech therapy.”

The concept of early intervention is one that Nagwa Khedr is all too familiar with. After a lifelong interest in child psychology and working with children with special learning needs, she became the first certified Developmental Individual-difference Relationship-based model (DIR) Floortime provider in Egypt.

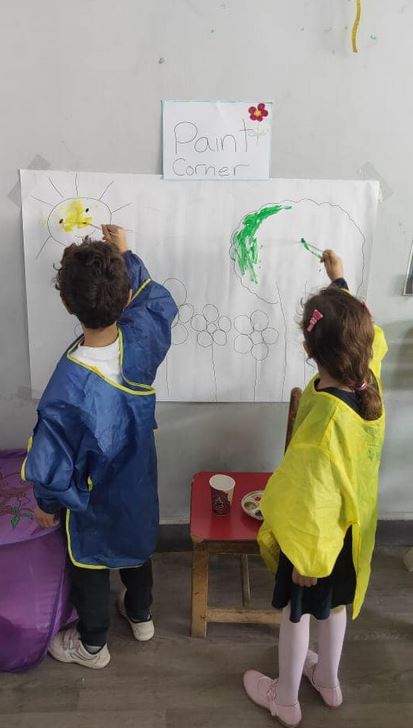

DIR Floortime is a relationship-based therapy based around play, where therapists and parents engage with the child through participating in their particular interests.

“It’s very child-led,” Nagwa explains. “We try to follow the child’s lead, we try to enter the child’s world, and then slowly try to challenge them in an empathetic, playful way. You see lots of good effects, especially in the communication and social skills area, as the environment of play really helps the family and the child connect with each other.”

As children grow beyond the early developmental stages, the time comes for them to enrol in the education system, which brings numerous hurdles for autistic children. Dahlia explains that one of the Egyptian Autistic Society’s (EAS) key aims is to facilitate ‘mainstreaming’, the integration of autistic children into mainstream schooling.

“I’ve always been pro-mainstreaming,” she says. “I’ve had a mainstreaming programme running now for over 15 years with EAS. We teach children things like raising their hand to ask to go to the bathroom, standing in line, writing on the blackboard or copying from a whiteboard. So all the skills that they would need, even how to play and how to request things, and if they’re non verbal we teach them through using pictures. We don’t only help with the transition, we enforce our system in mainstream schools.”

The system is efficient – but integrating it throughout all levels of society proves challenging.

“So far we’ve only been able to do it in private schools. The problem is in the public schools that you already have around 60 students in one classroom, and one teacher, so adding an autistic child into this environment will not benefit them.”

According to her, more funding must be allocated towards the public education system to create a more inclusive environment for these pupils. Thanks to EAS’ collaboration with the Ministry of Education, a law exists requiring every school in Egypt to be ‘inclusive’.

“But for this to be a reality, we need to reduce the number of students in class, upgrade the education of the teachers, and increase the number of teachers in class as well,” Dahlia explains.

As well as focusing efforts on mainstreaming pupils, Dahlia and the EAS have also launched a range of campaigns, and worked with the Ministry of Education, to bring positive change for autistic Egyptians. In 2019, the ‘Pass on the Light’ campaign took place, which brought special training on how to support autistic individuals to every governorate in Egypt. The EAS also recently partnered with McDonalds.

“They supported our students with vocational training and helped us spread awareness. We’re working to show off the skills that autistic people have that make them employable. Some are really good at inputting data accurately for hours, for example,” notes Dahlia.

Despite progress being made in leaps and bounds recently, there is still much progress to be made in making Egyptian society more inclusive to those with autism – and according to Nagwa, everyone has a role to play.

“We need lots and lots of awareness. With awareness will come acceptance. A lot of families have complained that they can’t take their child to a restaurant because people will stare if the child is doing any ‘atypical’ behaviour, which puts a lot of pressure on the parents. Actually, there’s this mindset in Egypt that, okay, my child is autistic, so I am not supposed to go out and let people see them, or talk about them,” says Dahlia.

“I believe that parents of autistic children should go out and educate others about their own kids and experiences.”

Such awareness may help undiagnosed adults further understand themselves if they suspect that they have autism. Dahlia explains that if people have reached adulthood without diagnosis, then the case is likely to be mild, yet a diagnosis can “relieve anxieties” for those who may have had a history of struggling with maintaining relationships and understanding social cues.

Dahlia claims that awareness must also be increased amongst the medical community.

“Until this day, Egyptian medical schools still don’t teach about autism, they only have one paragraph about it in textbooks. There is no degree programme that prepares you to be a therapist for those with autism in Egypt. This has led us to develop a partnership with Helwan University, where we welcome their fourth year medical students into the EAS centre to undergo practical training.”

From both Dahlia and Nagwa’s perspective, working with the autistic community brings as many delights as challenges. With an estimated 800,000 autistic people living in Egypt, the spread of awareness can only bring society closer together and build empathy towards those who perceive the world around them radically differently.

“Working in this field brings joy to me,” Nagwa claims. “I’ve discovered a lot about my own sensory needs through understanding those of others.”

Comments (3)

[…] Source link […]

[…] ‘With Awareness Comes Acceptance’: Shifting Perceptions of Autism in Egypt Egyptian Streets’With Awareness Comes Acceptance’: Shifting Perceptions of Autism in Egypt Egyptian StreetsRead More“englishspeaking” – Google News […]