Whether we notice it or not, we are constantly experiencing the world through our bodies.

Even if it is as simple as performing cultural rituals, such as prayer, or cooking and sharing meals with our families – every bodily act is also an expression of who we are, where we are from, and what we seek to achieve. In other words, our bodies can serve as a reflection of our identity and the surroundings, cultural systems and experiences that we regularly interact with. The more we seek change or freedom from these systems, the more our bodies also begin to perform actions that are outside of social expectations.

For North African and Arab women, the physical body is not explored beyond the purity of the body and maternity (physical experiences such as motherhood, pregnancy, and breastfeeding). Yet other experiences, such as their interaction with the world and the notions of shame, love and freedom, are not expressed or examined.

Camelia Chorsi is a Moroccan-Persian artist and healer, whose work focuses on exploring the experience of home within and without the body, the contradictions of shame and love, notions of freedom and fear, and notions of publicity and privacy. Primarily, her works questions how freedom is experienced through North African and Persian bodies, and how these experiences of freedom are ritualized and translated across cultures.

She is also the creator of N9CRA, a collection of unique silver work, with a focus on the metaphysical energy of the materials and the ancestral qualities the craft evokes (@n9cra).

Exploring freedom through North African and Persian bodies

For Camelia, women in Morocco and Iran are in ‘constant search for home’ as they have few options on how to navigate their lives. “You can conform to societal expectations and take care of your family, and essentially of men. You can accept your silence and be still until you forget what you wanted to say in the first place. You can embrace movement and sexuality, and fight the voices of judgment in an act of claiming your body. Lastly, you can escape, find new territories, and attempt to mother yourself through your displacement,” she says. “To live in a constant search for home. That is our form of freedom.”

As North African women are often classified as either ‘witches’ or ‘prostitutes’, Camelia says that this image forces them to actively expend energy, even subconsciously, to find the space to be expressive beyond this predetermined image. The idea of reclaiming their sexuality, as an animal and sexual being is not born from an act of defiance, but a right of existence, she adds.

“I’ve been searching for how to get what I want to say out of my body, and into the world. This has been a journey of connecting to the unconscious at a personal and collective level. I spend my life searching through my dreams and intuition, to make meaning of all the small pieces that create this wholeness that is me, and then to see myself as a piece of the whole that is us. That is how I find my freedom,” Camelia notes.

Through her words, she is in constant search of a collective truth to question it and suggest reminders and responses.

Cultural rituals and connecting with their bodies inside and outside of their homes

While most research on women’s bodies focuses on the personal level (maternal and reproductive), Camelia goes further by looking at the cultural and collective influences as well, particularly as women in North Africa and Iran do not live in individualistic societies, but in communities.

“The focus of my research has been within the translations of rituals of freedom. The rituals we partake in to connect ourselves happen on three levels— the personal, the cultural, and the collective. I have found that a woman’s embodiment across these spaces is most attuned to in rituals of affection,” she says. “Understanding giving and receiving affection as the basis of self love, and a secure attachment to the mother in the foundation of our early psyche. Acts of affection are connected to touch— the sense that activates the energy center of the heart.”

The most prominent example cultural ritual is the hammam, the bathhouse where women in the region routinely go to be scrubbed and groomed. “In this ritual, we prioritize our bodies. As we get rid of the dead cells, we are making space for more life, and essentially our growth. When we detox our largest organ, we purify our receptivity to others, and our intuition,” Camelia says.

For many women, mundane acts such as cooking and sharing a meal with their families give a self-defining sense of home within their bodies – reminding them that their bodies are vessels of connectivity as we trigger a sense of belonging. “Walking in public also awakens a similar sentiment, as we form a sense of bodily independence through navigating the spaces around us, that we have named a home,” she adds.

‘Memories of Sound’ and Family Rituals

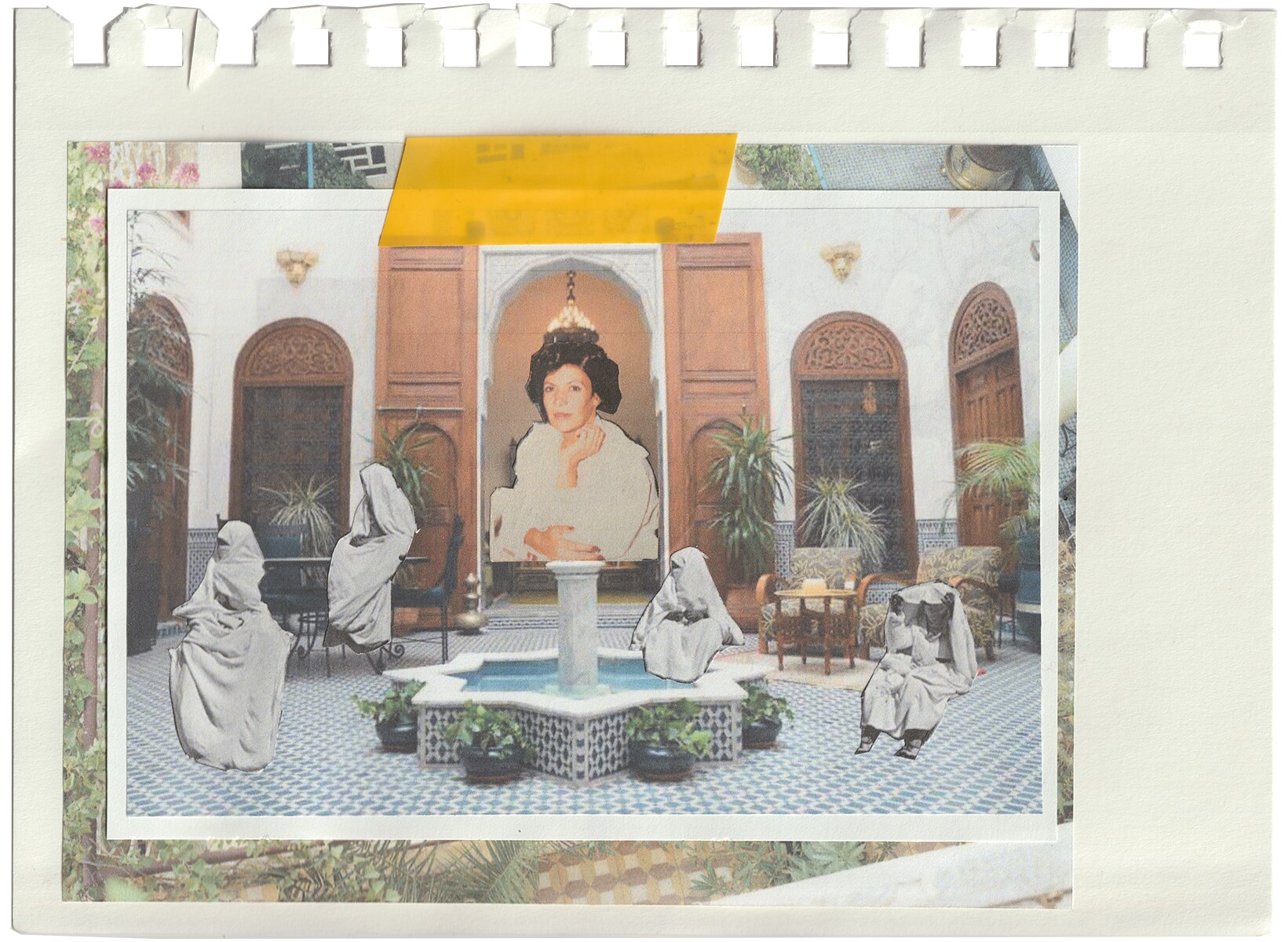

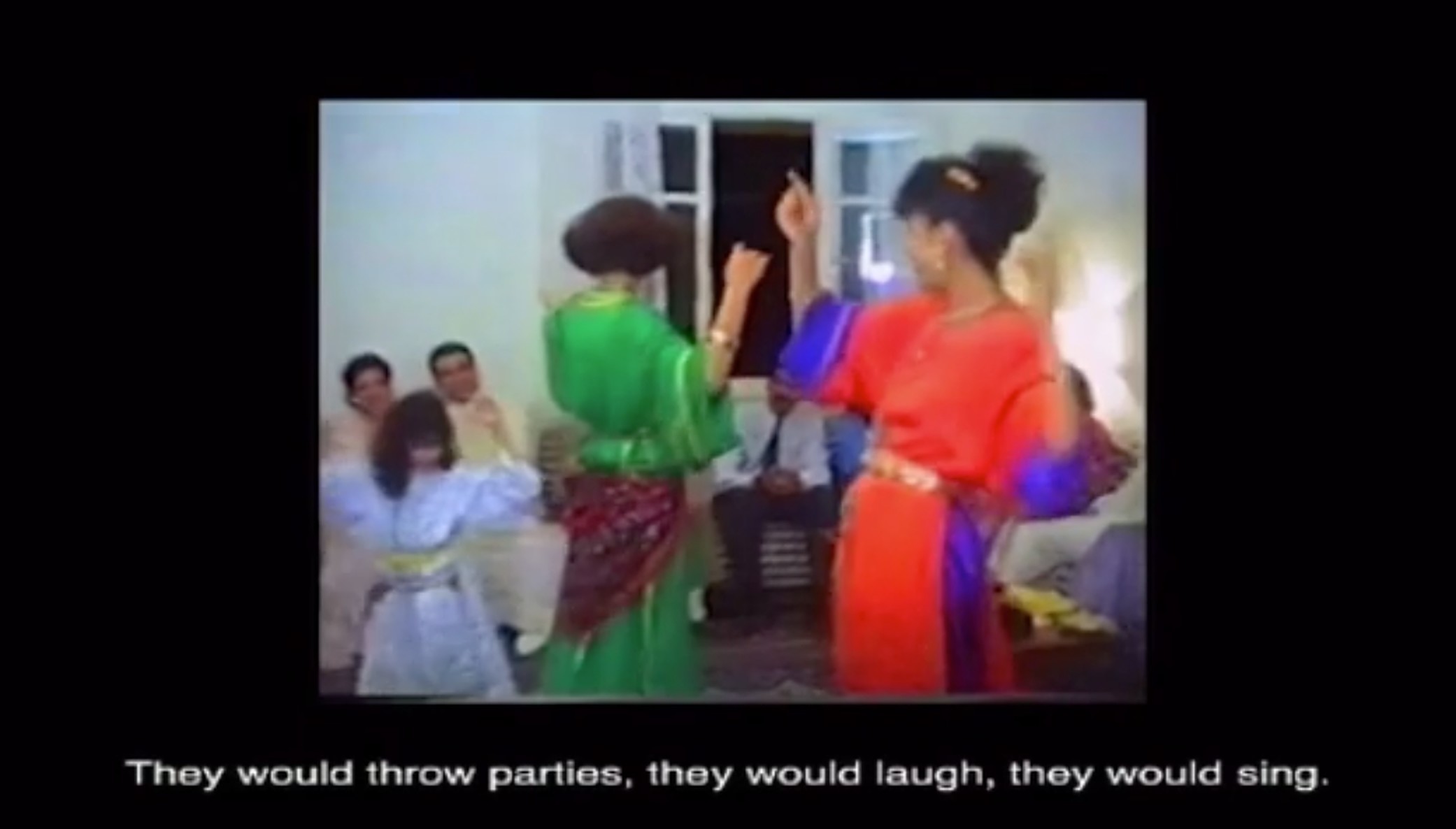

In her audio-visual collage ‘Memories of Sound“, Camelia explores the fractures of nostalgia through her father’s home video footage of the 90s and early 2000s in Casablanca, Fes and Tangier. In the audio-visual collage, there are videos of women throwing parties and dancing inside their homes, expressing an act of connecting with their bodies through family celebratory rituals.

“There are sonic imprints that we are attached to unconsciously, through our mothers’ experience that is passed on to us in the womb. These sensations of security and belonging are what inform my nostalgic longings today— the sounds of music, dancing, sharing, and my family’s voices,” she says.

Celebration is a widely significant part of Arab and Persian culture, and the act of gathering alone is a call for celebration, food, and music. “In the video I revisit my parents’ union, travels, and wedding, by reintroducing myself to the memory of sound. The video opens with my grandmother’s narration, explaining how family dynamics are no longer the same. The gatherings have become rare, and celebration is assigned to select occasions and holidays each year. As a result of the social shifts, and my physical distance from home, I have consciously imprinted these fragments of collective memory,” Camelia adds.

Rituals of sacrifice and prayer

Tradition is another level of exploration of how women in the region connect with their bodies. In the photo-series, Rituals of Sacrifice, and the film L’Eid, Camelia documents tradition and religious rituals in the region as an observer. “In stepping back and documenting each step of the sheep’s killing, skinning, preparation, and feast, I consciously accept the collective experience. In this film, I raise questions around what proof of devotion means— through pride, performance, and role conforming. I am able to explain this tradition cross-culturally through simple documentation,” she says.

“In Islam, we participate in this sacrifice to prove our devotion to the divine. Culturally, this ritual connects us to our bodies because it reminds us of who we are. In the slight differences in how the sheep is sacrificed and prepared, we are reminded that we are Moroccan, and we belong to our family. The eldest son makes or oversees the incision, and bleeding out. The youngest woman cleanses the intestinal sac, to be made a delicacy, as a marking of her transition into womanhood. Every role is well understood and thoroughly internalized with each responsibility. In this way, notions of freedom can be established, or challenged in definition and defiance,” Camelia adds.

Camelia’s work reminds us that the body is the basis of subjectivity and self-expression, and that the body largely influences a woman’s sense of self, image and identity. To produce a sense of self, women partake in body-related acts, such as body rituals, pursuits of beauty, and family rituals of cooking and gatherings to manage their body image and self-identity.

When we grow separate from the body rituals of tradition and affection, and products of our ancestry, we also trigger a separate sense of self.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comment (1)

[…] Egyptian Artists Explore Sinai Through Art, Photography, and Storytelling Inside North African Women’s Bodies: Exploring Shame, Love and Freedom […]