A blue lotus floats its way upstream, and the sky canvases parallel to the Nile. In Egypt, it seems as though one can never get enough of the color blue – historically, artistically, and theologically. Blue is a fixture of Egyptian culture and has been for centuries; little scarab amulets, painted temple walls and most recently, evil-eye pacifiers.

But blue, the ancients were quick to realize, was not a naturally occurring color; the sky was untouchable, and there was nothing to powder down to dilute into paint. Pigments at the time were sourced from the surface soil, most being earthy and warm as a result of their origin. It was an unfortunate arrangement for a culture whose essence relied on the existence of blue in any capacity.

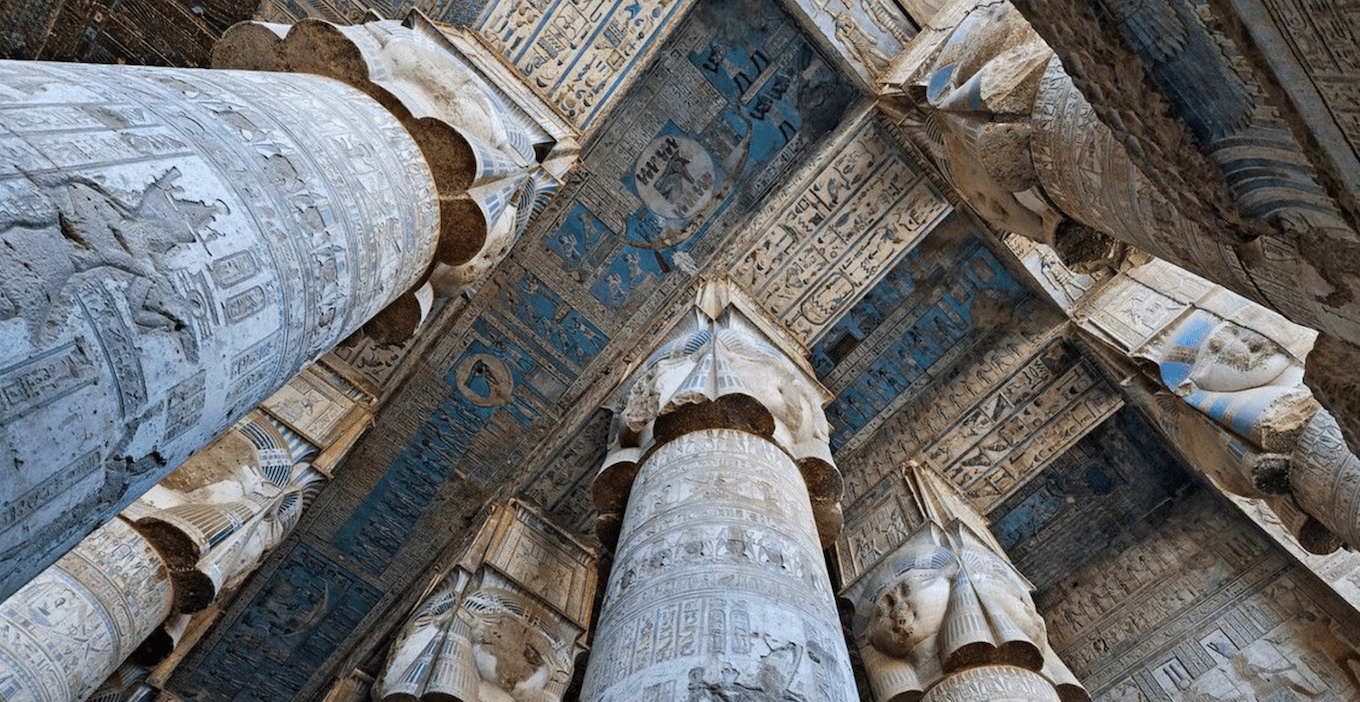

For ancient Egyptians, blue was associated with the sky, the Nile, and thus its importance eventually expanded to include representations of the universe, fertility, and creation. Nun, or the primeval waters of chaos, embodied those concepts of rebirth and creation – and unsurprisingly, those waters were believed to be blue as well. As a result, long-lasting symbols such as that of the Nile and creator-god Amun necessitated the color, almost intimately.

To take it a step further, it was believed that the “hair of the gods was made of precious Lapis Lazuli” – a metamorphic, deep-blue stone that to this day is considered semi-precious.

A solution needed to be found.

To add to an already long list of innovations, ancient Egypt gifted the world its first blue pigment: a synthetic, highly-coveted paint derived from ground limestone, sand, and copper minerals (such as azure or malachite). Heated at temperatures of 1470 – 1650 degrees Fahrenheit, the resulting glass would be powdered and mixed with thickening agents such as egg-whites to produce an opaque, “long-lasting paint or glaze.”

Otherwise known as the ever-famed Egyptian blue.

Egyptian blue was the ancient world’s first introduction to synthetic paint development, and remained essential throughout the centuries. The hue was held in incredibly high regard; it was used for Pharaoh tombs, statues of gods, and ceramic art depicting the divine. Whether the discovery was beginner’s luck or pure, calculated design, it was a “seriously impressive accomplishment” for an ancient civilization. Calibrating the correct circumstances, with that level of temperature control, would have been a major obstacle.

The unwavering consistency of this pigment was a testament to the finesse of ancient Egyptians, and the degree to which they were able to execute their craft.

Today’s Egypt is no different. Although the love behind blue has taken on more Abrahamic interpretations, there remains a constant: blue is tied to spirituality, divinity, and protection. Perhaps the most prevalent example is that of the nazaar amulet, or the evil-eye pendant. Now a fixture of both Egyptian home and heart, the nazaar is believed to ward off the violent energies associated with envy. As with most Eastern cultures, blue has come to embody the absolute and infinite, as well as transcendental tranquility.

It’s association with divinity, though, doesn’t live and die with the nazaar. Rather, another common symbol seen in Egypt is that of the Hand of Fatima (also: Hand of Hamsa, or Khamsa): another pendant often depicted in blue. Fatima is said to have been the daughter of the Prophet Mohammed, her open palm an embodiment of “inner balance, faith, and patience”. Each of her five fingers represent the pillars of Islam: prayer, faith, Mecca pilgrimage, almsgiving and Ramadan fasting.

Though blue is not featured in Islam exclusively; in fact, most of its Abrahamic roots are founded in Christianity. Many Egyptian churches retain its use in art to emphasize the infiniteness of the sky and the eternal world. Most famously, the color most associated with the Virgin Mary is dark blue; a woman who, in herself, combines both the terrestrial and celestial.

Regardless of where it lingers, there is truly no color more beloved in Egyptian culture than that of a pure symbolic blue: its use generous and its importance undeniable.

Comments (3)

[…] which, the glass is melted in the kiln, or oven. Blue is by far the most distinctive color in circulation, much like in ancient times. Most kilns are made out of mud-brick, laid in a pinwheel or […]

[…] https://egyptianstreets.com/2021/11/27/egyptian-blue-a-hue-that-made-history/ […]