25 January, Eid El Shorta (Police Day), of 2011 fell on a Tuesday. I was sitting next to my mom in – the newly opened at the time – Tivoli Dome in Heliopolis, happy I had a day off school. I had just turned ten a couple of months earlier and I listened while my family talked about the danger of technology and the ‘kids’ who thought they would start a revolution through Facebook. I remember very clearly the worry on my mother’s face, and I remember equally a family member assuring everyone that nothing will come of it.

He could not have been more wrong.

Children are often forgotten amidst events of collective violence. They become symbols of tarnished innocence or cards to draw international empathy with. Children are always “the future”, but this ambiguous haze is drawn around us because the minute we are no longer children, we are sidelined for being youth.

It seems like people often forget that children don’t necessarily forget, and that what we witness and experience can very much shape who we become.

At the time, I lived in a small and enclosed neighborhood between Al-Mahkama and Ain Shams, small enough for almost everyone to know everyone else. During Gom’et Al Ghadab (the Friday of Anger), my family still were not convinced something as major as a revolution could take place, so we visited my grandma, who lived close by. I remember jumping at the dining room table while eating when I heard loud chanting and marching that felt – at the time – deafening; “Selmeyya! Selmeyya! Selmeyya!” (Peaceful!) over and over and over again. My father shook his head in disappointment while my mother tried to reassure my terrified and crying younger sister, who was barely eight.

When we left my grandma’s that day, a freshly painted mural greeted my sight at the side of the building, a graffiti painting of Khaled Said smiling, with the words “El Shaheed Hayy” (the martyr lives on) written in beautiful calligraphy next to him. It has been refreshed multiple times since.

I can detail every single night and day in lockdown during the three months I spent at home.

My parents often sat in the living room, at odds with their stances regarding the revolution, fighting quietly while holding my younger sister between them. I stayed away from them, hiding in my room with our housekeeper, who was maybe eighteen then. When the legan sha’beyya (peoples’ committees) started due to the release of thugs, it was our housekeeper who gave me a conduit pipe and a pan to hold at night. She’d sit next to me and play Zee Alwan, the Bollywood channel, and engross me in conversations around cute characters and their love stories, while making sure I held onto the pipe and pan she’d given me, to distract me from the sound of gunshots and screams right outside my window.

Some nights though, none of it could be ignored, as troops fired enough shots and received enough molotov cocktails back that the night sky would light up as if the sun were rising once more.

Many of the memories I have with the revolution are tied to potatoes. At some point, the supermarkets had nothing left to sell or even hand out. Weeks passed where we ate nothing but potatoes; baked, fried, and boiled. Our neighbors often exchanged necessities, a couple of onions for half a cup of sugar or a box of tea for a bottle of frying oil. I’m not unaware of my privilege here; I never went hungry despite the circumstances, unlike many others.

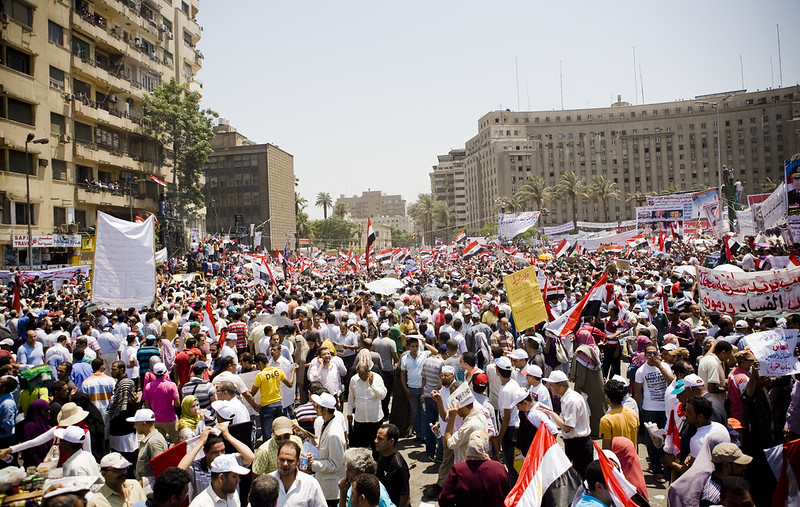

The first time I left home to go back to school, I saw faces. The more months passed, the more faces I saw. First came 27 May, 2011 and the reigniting of the revolution, then came the August arrests, then came Maspero in October of 2011. Martyrs, political prisoners, disappeared persons, heroes, and icons. Graffiti art and posters were constantly filling the streets.

I would not say things were quiet, but I went back to school and instead of playing a’rousa w a’rees or soccer, we now asked questions to each other:

“Babak feloul?” (is your dad feloul?) Feloul is a term popularly used by Egyptians during the revolution to refer to supporters of the old, Mubarak’s, regime.

“Mamtek ikhwan?” (is your mom with the Muslim Brotherhood?)

“Ana kont fel midan ma’ Baba! Ento konto fein?” (I was in the Square with my dad, where were you?)

Later, we recognized that some of our schoolmates lost family members, breaking the carnival-esque image our friends in Tahrir had painted. Our playgrounds were politicized much like the streets, in very petty and mean ways, like only children’s spaces could be.

When I asked a group of friends about things they forever remember and associate with the revolution, the answers ranged from names to processes to objects and even emotions. Protest songs, martyrs whose names they didn’t know but whose faces were scorched behind their lids, the names of artists and political activists, and moments where an uncle taught a nephew how to mix a molotov cocktail and a father taught a son how to hold a gun or a knife.

Despite official discourses, some of us so-called ‘children of the revolution’ carry our memories and stories close to our chests. It has been and always will be up to people to retain and tell their stories, and it is times like these that prove how impactful and important oral histories are.

Children are sequestered; protected in some sort of safety bubble enforced by their parents and the adults around them under a misguided notion that if they tell us to close our eyes and block our ears, our experience will be less brutal or scarring. I’m not a child of El Midan (the Square), but I’m a daughter of Thawra (the revolution) nevertheless.

Comment (1)

[…] بعد 11 عامًا ، أذكر ذكريات طفولتي عن الثورة المصرية […]