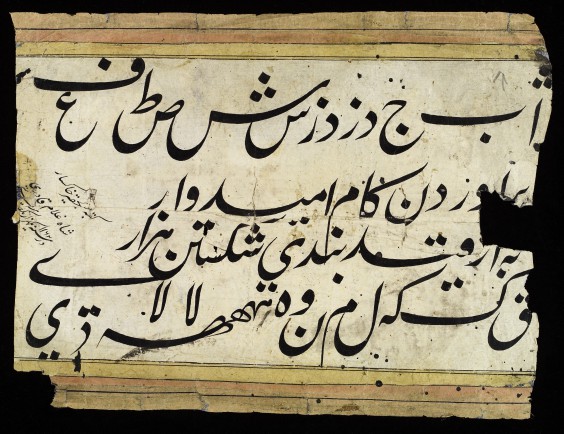

Calligraphy and Arabic are sisters of the same marrow – one has not existed without the other. From the inception of written Arabic, well after an era of oral tradition, taffy-curled lettering has been the staple of religious and historical documentation, of mosque walls and tapestry design. The art of calligraphy cannot ideologically – or practically – be thought of as separate from Arabic.

Writing Arabic is scripting art.

Writing Arabic is a form of calligraphy, by virtue of flow and form.

Arabic’s earliest written form surfaced in the 4th century CE, evolving from what was then known as Nabatean: a pre-Arab civilization that saturated the Levant and northern Arabia. This was an era prior to that of islam, where Arabic was a recited tradition rather than a written art. For centuries, most notably after the revelation of the Quran in the early 7th century CE, Arabs were speakers rather than scribes; they were poets and verse-rhymers, sharp-witted and fierce.

With the advent of religion and the need to document what was now a widely growing faith, Islamic scholars began writing down Quranic verses, qasa’id (long odes), and much of their poetry. Arabic writing flourished with the spread of Islam, despite having been present for centuries prior to it. Quite soon after it flew through North Africa, it became the source of art rather than simply the inspiration for it.

The word for calligraphy in Arabic is khatt: derived from the term for line, design or construction; it’s a fitting name, “because one of the most striking features of the script is its use of lines, whether flowing with sweeping curves or bold and angular.”

By nature, Arabic script is cursive – meaning letters are tail-joined depending on which form the word takes. Naturally, this means that each letter in the Arabic alphabet has a minimum of two forms and upwards of four (start of the word, middle, end, unjoined).

Al qalam, or “the pen” used for Arabic calligraphy is traditionally made of dried reed or bamboo. Although this staple has long since evolved; no longer is Arabic printed on papyrus or parchment, but rather when the Islamic Empire was at its height, calligraphy was everywhere: containers, carpets, building inscriptions and coins; there wasn’t a facet of banal society that stitched Arabic wasn’t embedded into.

This continues to be true today as well. Egypt’s homes are decorated with Quranic verses, hand-written or etched into wood, cafes embellished with poetry stanzas and kind mashallahs. Arabic teachers will pull on ink pens, and government officials will sign papers with liquid, stunning script – effortlessly. Letters are joined and repeated into patterns and mosaics at historical sites, and handwritten street signs are a staple of older districts.

It’s safe to say that Arabic is more than a national language, but an artform designed to exist as a masterwork of design and penmanship – not just as documentation.

Comment (1)

[…] Arabic Calligraphy: A Written Revolution […]