The old Gamaliya quarter in Cairo is humble and bustling, cobblestone streets and squat buildings. In one home, nestled tight between two others, a son is learning how to hold a pen upright; that son would soon become one of Egypt’s thought-leader figureheads and a Nobel Prize laureate.

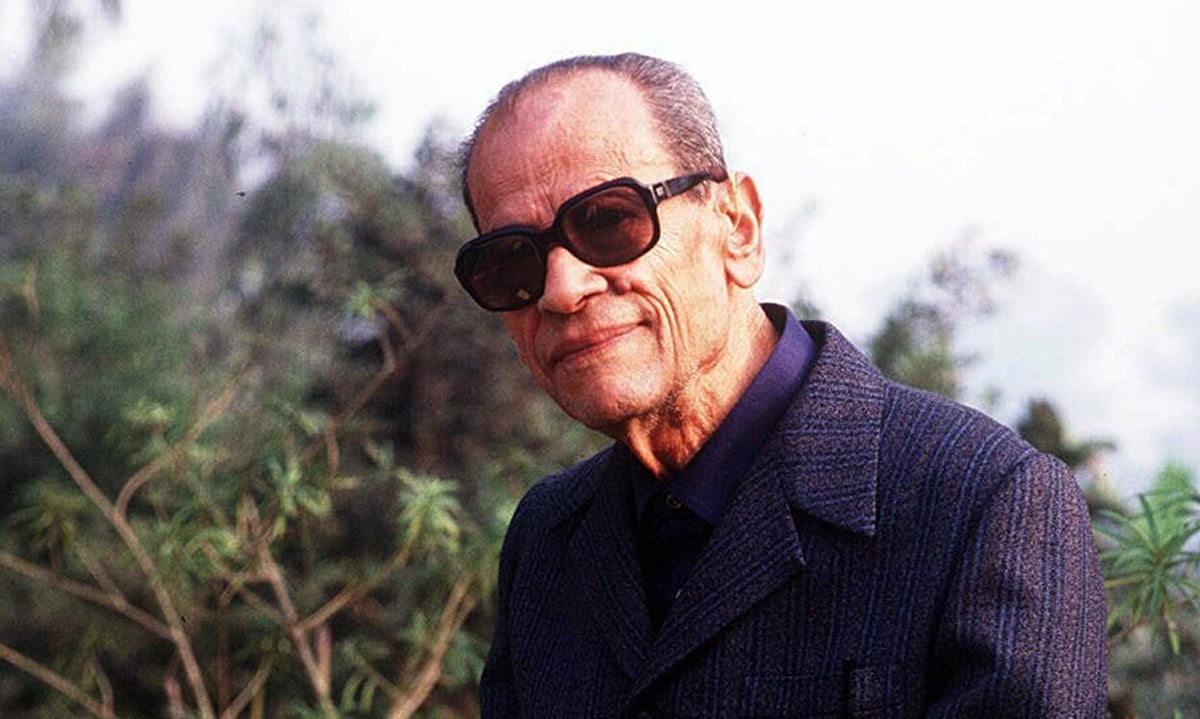

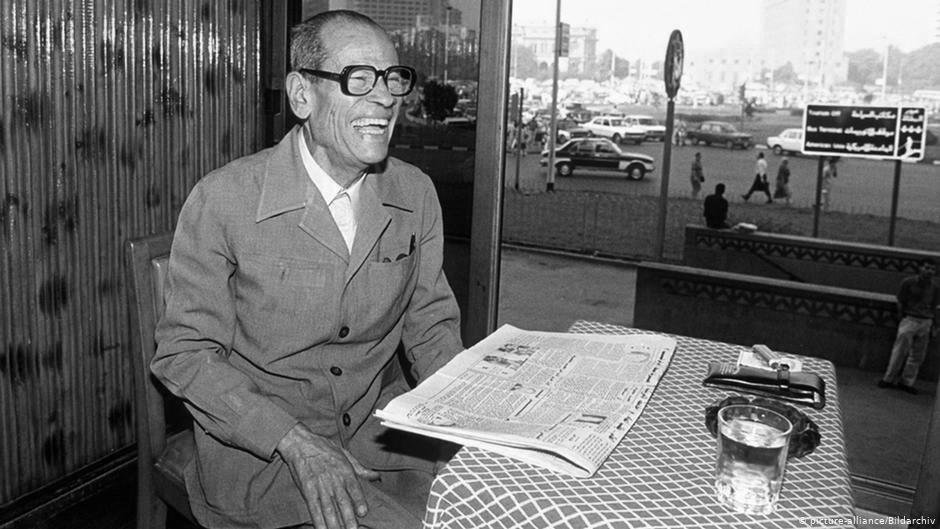

From the controversial to unrivaled colloquial story-telling, Naguib Mahfouz has immortalized his name in local and international literary circles. Straying from romantic visions of Egypt, Mahfouz reacquainted the world with a human reality, one with fault-lines and furies, with love and betrayal.

Mahfouz reacquainted the world with modern Egypt.

A Child of Gamaliya Writes

Born on December 11, 1911, Mahfouz was raised in Cairo’s modest Gamaliya district, in a house packed with seven siblings. Being the youngest by far, Mahfouz is recorded as having felt like an only child; with nearly ten years between him and his next-youngest brother, Mahfouz was left scavenging for attention among preoccupied minds. During his youth, he lamented his lack of sibling dialogue, and revisited the bonds within his later work.

Although not always connected to his family, Mahfouz’s childhood was noted to be a happy, stable one rife with religion. The first decade of his life, Mahfouz spent in Gamaliya and allowed it to monopolize his imagination. For many of his earlier novels, the grit and charisma of Gabaliya’s alleyways saturated his writing. He drew much inspiration from his young years, reimagining streets and his own family home several times in novels Children of the Alley and Midaq Alley.

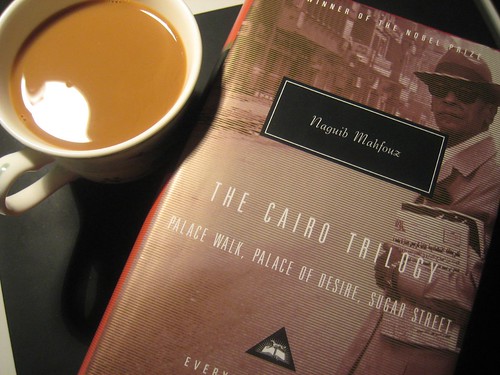

The renowned Cairo Trilogy, which earned him a Nobel Prize for Literature (1988) and was lauded internationally, is said to have featured the ins and outs of Mahfouz’s own childhood from clandestine hiding spots to rooftop family gatherings. Even long before his dip into more influential pieces, Mahfouz’s journey began when he was in his early years; he was an avid reader of historical novels and murder mysteries, and later found himself in the works of Taha Hussein, Muhammed Husayn Haykal, Ibrahim al-Mazini—who “served him as models for the short story.”

Revolution’s in the Air

Patriotism was brought into Mahfouz’s world in 1919: Egypt’s political climate was in swing, and the first modern revolution cusped just short of his own door. Mahfouz became enamored with themes of nationalism, between the revolutionary and colonial tides of his era. Although, it’s worth noting that this romanticization of the political sphere fizzled and died around the time of Egypt’s 1952 bout of unrest. Unlike earlier visions of Egypt, Mahfouz was a harsh critic of Gamal Abd al-Nasser’s despotic approach to power (per his book Before The Throne, 1983).

In the early 1920s, Mahfouz’s family relocated to the suburban, sleepy Abbasiya. In similar fashion, he drew much inspiration from his new surroundings, and in the midst of his literary trails, Mahfouz found romantic love.

While his faculties for writing and numerics were notable, Mahfouz chose to pursue a philosophy degree at Fouad University (i.e. Cairo University). He graduated in 1934, and found inspiration in the writings of Abbas al-Aqqad. From then on, Mahfouz was a jack-of-all-trades in his career life; administrative and secretarial jobs were offered to him at Cairo University, as well as a variety of other civil servant positions until his retirement in 1971.

God-Worshiping Disbeliever

Mahfouz’s first novel Khufu’s Wisdom was published in 1939, and his prolific nature managed ten more publications before the revolution of 1952. A brief hiatus followed, where his disillusionment with the state had reached new highs, and inspiration became a scarce commodity.

This did not, however, shift his position as a lover of the controversial. Over his nearly 50 published novels, Naguib Mahfouz has earned himself a ferocious set of adversaries. Touching on the taboo and the unsavory in his Cairo Trilogy, while dabbling with personifications of God in Children of the Alley, Mahfouz slowly climbed the literary echelon, labeled a “monument” of his art by those most enamored with his gusto – and a heretic by those less so.

Attempts on Mahfouz’s life are a key facet of his personal history. Between his harsh, gritty display of Egyptianism in the Trilogy, to his less venerable, but doubly charged use of Islam in his writing – despite considering himself a devout Muslim – many have not only called for the banning of his books and burning of his legacy, but the taking of his life.

On more than one occasion, no less.

Islamic militants attempted to assassinate Mahfouz in 1994, leaving him with a stab wound to the neck and an inability to write consistently. It was then that he resorted to producing short, potent fictions based on his personal dreams and recollections. Dubbed Dreams of Convalescence, multiple versions of this collection were published by the American University in Cairo Press (AUC Press).

Mahfouz in Translation

The praise of Naguib Mahfouz is perhaps the only thing about him which did not remain local. His books were translated across dozens of languages, in dozens of countries, with the primary publisher being AUC Press after an agreement signed by Mahfouz in 1985.

He’s heard praise from the likes of world-class scholars such as Edward Said, and Egyptian revolutionaries such as Alaa al-Aswany, who called him the “father” and “founder of the new Arab Novel.”

“I cannot understand Egypt without Mahfouz,” writes Tahar Ben Jelloun, a renowned Moroccan author.

And it appears, not many can.

For better or for worse, Mahfouz is a lens many look through to understand Egyptianism at its roots. Oddly, it is this fact that gave credence to his adversaries; for many, Mahfouz was a cynic who understood Egypt through misfortune and poverty, through skewed politics and fatal love. His very popularity had become justification for his critics – those who were convinced Mahfouz’s work was an exaggerated, dramatized version of reality that rested solely on its capacity for grit.

From death threats to assassination attempts, it’s not hard to extrapolate just how polarizing Mahfouz was in local and international milieus.

Despite this, Egyptian literature would not look the way it does without his contributions. It’s for that reason, paired with his bravado and literary prowess, that Egypt has venerated him as one of its finest modern writers and a postmodern inspiration for many young voices.

The Naguib Mahfouz Museum was completed in 2019 and remains a testament to his legacy.

Comments (8)

[…] على جائزة نوبل نجيب محفوظ جلبت سي السيد في الحياة بين القصرين (بالاس ووك ، 1956): […]

[…] prize laureate Naguib Mahfouz brought Si El-Sayed to life in his Bayn al-Qasryen (Palace Walk, 1956): the first installment of a […]