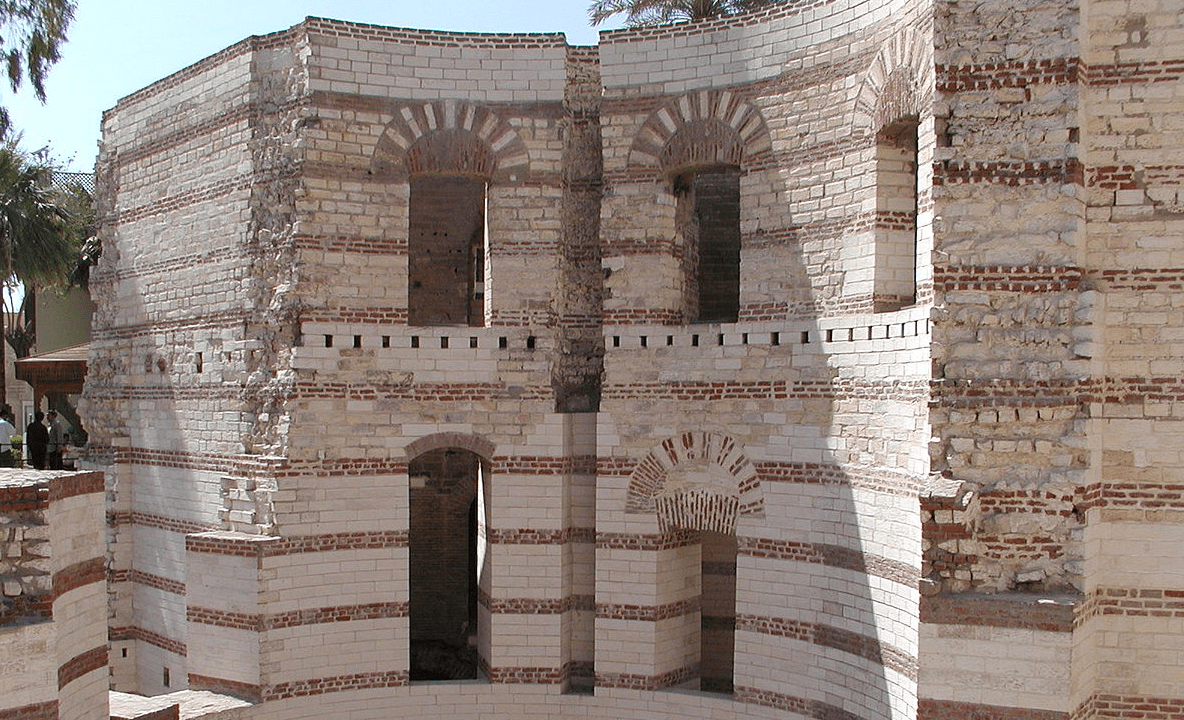

The Fortress of Babylon echoes with memory; limestone and mudbrick lock together, footsteps wander narrow halls, and a collective nostalgia is created in the silence. Sitting on the pinched streets of Old Cairo, the fort is cupped by culture; it is considered a distinguished product of Egypt’s Roman era, and an illustrious monument in Cairo’s universal architectural history.

Although fortresses are known as houses of violent history, Egypt’s Babylon was not intended to be a fort at its inception. Initially, the site was used as a harbor entrance by the Ptolemies for a canal linking the Red Sea to the Nile between 246 and 46 BC. The canal was attempted as far back as the twenty-sixth Pharaonic dynasty, with little success, but saw prominence when re-established under Persian rule between 521 and 486 BC.

The fort itself, however, came into being under the commission of Roman Emperor Tarjan in 107 BC. Scribes of the time write that “Tarjan went to Egypt and there built a fortress with a powerful and impregnable citadel, having an abundant supply of water.”

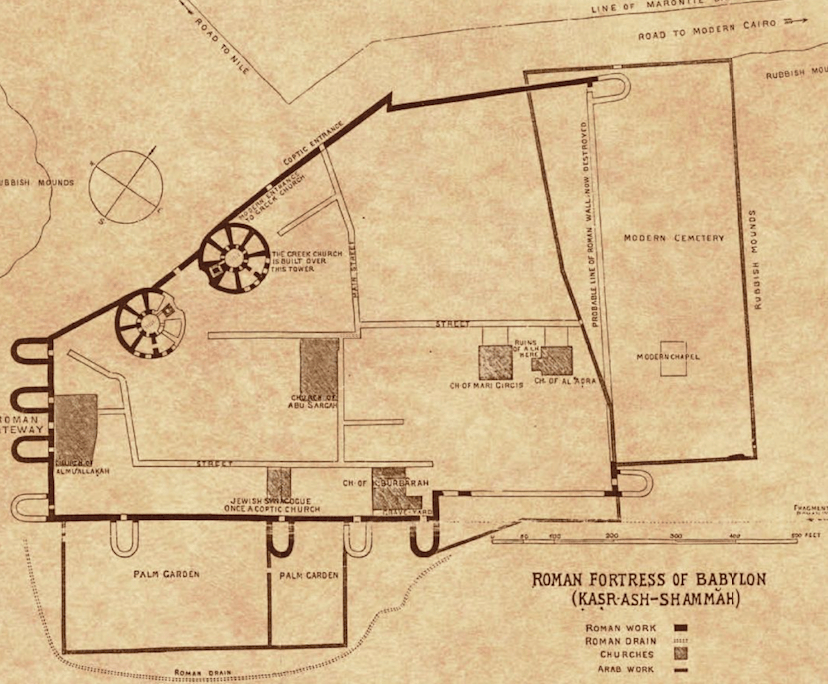

It is believed the fort’s foundations were initially set by Nebuchadnezzar, king of Medes and Persians, who called it the Fortress of Babylon after his own Macedonian capital, i.e. Babylon. Upon first glance, it was a typical Diocletianic-era fortress designed to serve a field army; it had high walls and an isolated, elevated location, and was built with dense planning.

Still, Babylon possessed idiosyncrasies that set it apart from the structures of the time – its second purpose as a harbor, and the fact “the size and strength of the fortifications were much more solid than those of any other Diocletianic fortress in Egypt.”

Additionally, archeological evidence suggests that a bridge existed over the Nile and connected to the western gate of the fort, which was the only one of its kind.

By the Arab conquest of 640 AD, the fort had expanded to include forty foot outer walls, a moat, and a nationally famed port with two nilometers and the aforementioned Red Sea to Nile canal. It was an ideal location that controlled traffic and trade, but also became a “refuge of Coptic Christians, who were persecuted by the Roman Christians in Alexandria.”

The fort was never a seat of the Egyptian government, but some argue that Cairo evolved around the fortress, and owed much of its glory to the location. As a result, for years, Europeans misguidedly – or perhaps with romantic intent – referred to Cairo as Babylon.

To this day, although only a fragment of the fort remains, the Fortress of Babylon is a vision of several of Egypt’s bygone eras.

Comments (0)