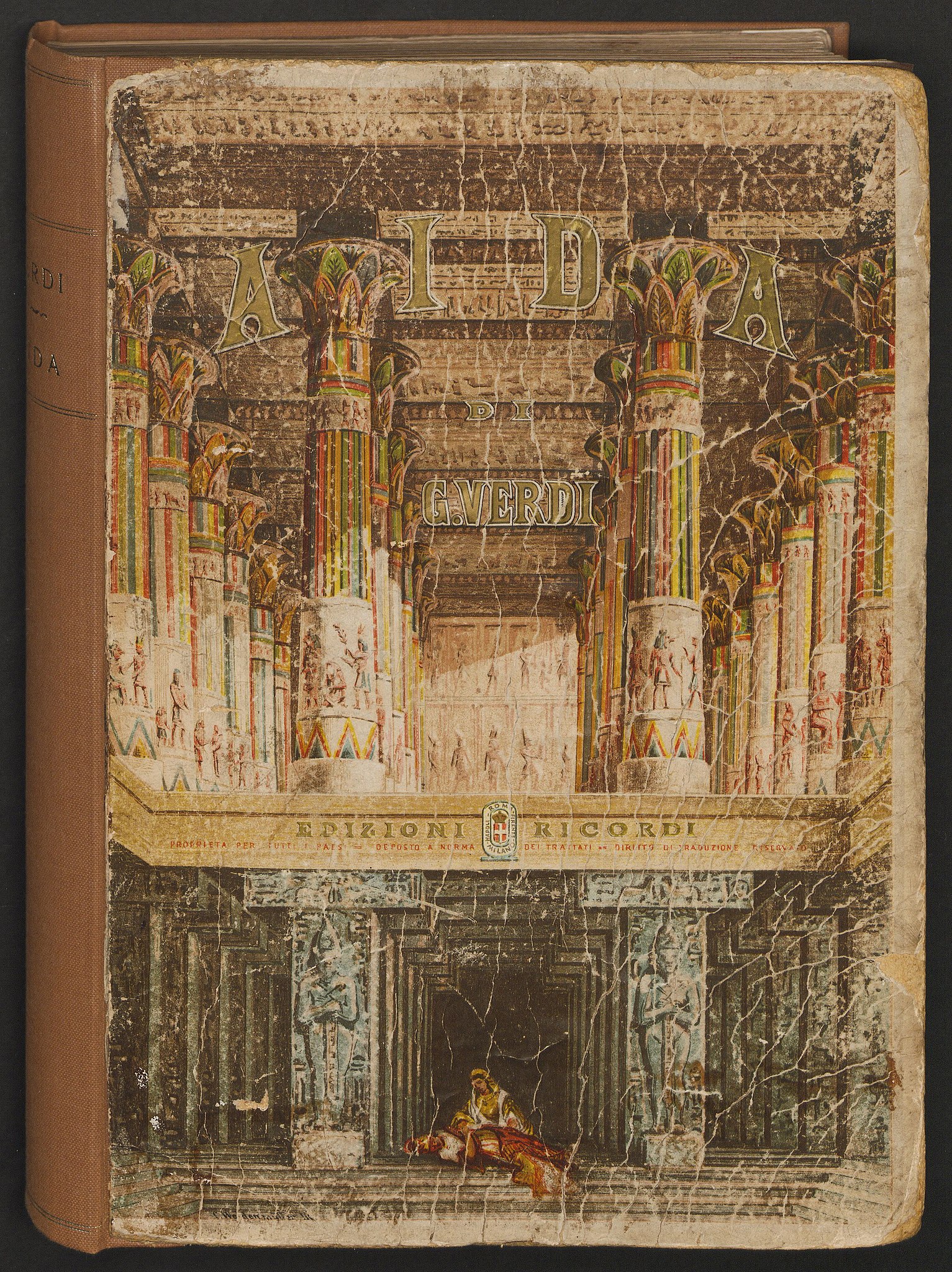

Dovetailed with Egyptian theatre narratives is Guiseppe Verdi’s ‘Aida’: an opera saturated with tragedy and desire, a vision of Aida on her knees mourning a lover, of Radamès’ undying devotion to his own passions.

‘Aida’ explores the majesty of the ancients and pairs it with the brilliance of an orchestra. From Verdi’s bellowing score, to the intricacies of love and envy, ‘Aida’ has remained ripe in the public consciousness for well over a century, cementing its position as a monument to Egypt’s cultural past.

Though the score’s fame is not confined to Egypt; considered “one of the most regularly performed operas across the globe,” ‘Aida’ has recreated Egypt time and time again on stages worldwide, remaining as “beloved by directors as ‘Carmen’s’ Spain or ‘Madama Butterfly’s’ Japan.”

‘Aida’ is a timeless tale of desperation against the backdrop of war, and has been a reference point for countless theatre explorations since its initial debut in 1887. Based on a story penned by French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, it was composed by Verdi as a celebratory hymn inaugurating the Khedival Opera House in Cairo; unfortunately, ‘Aida’ would not be ready in time. As the Franco-Prussian war enveloped Paris, the production and shipment of costumes was halted. Rather, the House officially opened to the score of Verdi’s ‘Rigoletto’, much to Verdi’s own chagrin.

‘Aida’ would later premiere in Egypt on 24 December 1871.

Paired with a powerful, lung-cramping score, ‘Aida’ tells the ancient story of two star-crossed lovers in the throes of their affair: Aida, an enslaved Ethiopian princess held captive in Egypt, and Radamès, an Egyptian general chosen to lead war with Ethiopia. The opera is a calculus of conflict—internal and external, exploring the concepts of nationhood, personal loyalty, and lovers’ suicide.

Set in ancient Egypt, ‘Aida’ attempts to re-envision an unseen era.

Still, it has not escaped the critical eye of Edward Said, a Palestinian scholar who dedicated much of this learning to the deconstruction of Orientalism—a premise he coined and conceptualized—in the Middle East and beyond. Of ‘Aida’, he wrote: “[it has] an anesthetic as well as an informative effect on European audiences;” in his eyes, ‘Aida’ was little more than the Eurocentric ideations of men unfamiliar with Egypt as a whole.

This claim, while abrasive, is only further supported by Verdi’s own sentiments; The Guardian documents him having little feelings of admiration for Egypt. When working on ‘Aida’, he was recorded as having confessed “if anyone had told me two years ago: ‘you will write for Cairo,’ I would have considered him a fool.” Khedive Ismail swayed him with promises of a grandiose, fabulous staging—and thus, Verdi agreed.

For Egyptians, however, there is no conflation between ‘Aida’ and its creator: the opera remains well-loved, and regularly played at festivities across Egypt. Impresario Neveen Allouba describes ‘Aida’ as a representation of Egypt’s past, “it’s our history.”

Alternatively, Magdy Saber, president of the current Cairo Opera House, believes there is modern significance to ‘Aida’. “It’s very important to the history of the Egyptian military,” he explains to The Guardian, “because Radamès [Verdi’s tenor hero] is the head of the Egyptian military and when he commits a crime, he admits it—so it’s about the honour of the country’s history and at the same time the honour of the Egyptian military.”

Be it past or present, it is undeniable that ‘Aida’ has remained a core node in the Egyptian arts from its initial debut—though that does not negate critical assessments made by modern and postmodern intellectuals. To consume media is to understand both its vitality and its validity, and as proven by ‘Aida’, the two may be worlds apart.

Comment (1)

[…] A History of Egypt’s Opera ‘Aida’: the Captivating and Controversial | Egyptian Streets […]