Long before the advent of mass media and live coverage, conflict – and the diplomacy that often follows after it – was only documented through art and poetry propagandized by each ruler.

The Battle of Kadesh was a culmination of decades worth of conflict between ancient Egypt and the Hittites, exacerbated by the Hittites’ capture of Kadesh from Egypt.

Ramesses II, a famed New Kingdom ruler who had been revitalizing Egypt’s authority through conquests and expansions, set his sights on Kadesh (in modern-day Syria) in 1275 BCE, and bid to conquer it against King Muwatalli II of the Hittites.

It was the largest recorded chariot battle in history, with a total of 6,000 chariots deployed in the war. Strategically, both sides acknowledged the Hittites’ upper hand at the start due to a rash decision by Ramesses to push ahead of his primary army with 20,000 infantry and 2,000 chariots – as recommended by Hittite double agents.

Upon reaching Kadesh, Ramesses was ambushed by 40,000 Hittite infantry and 3,000 chariots, an onslaught that steered the tides of war in favor of Muwatalli. Despite being outnumbered, Ramesses’ chariots eventually brought balance to the battle.

The remainder of the battle is a historical blur. Scribes from both civilizations declare the victory of their respective king but today’s historians believe the battle ended in a draw. Kadesh was never reclaimed by Ramesses, and the Hittites suffered significant losses, both militarily and economically.

Sixteen years after the battle, in 1259 BCE, the two kingdoms realized there was no victory in sight for either; instead, they put aside their warring past and proposed binding articles of peace known today as the ‘Treaty of Kadesh’.

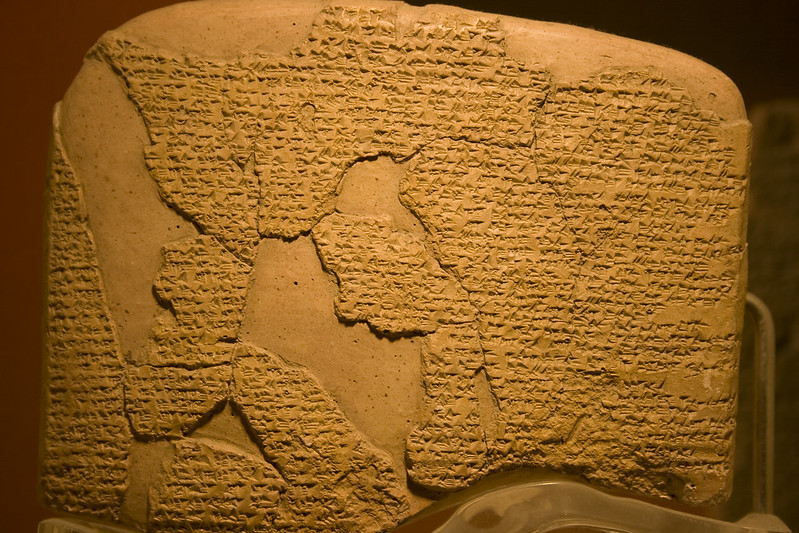

Each king was gifted a silver tablet of the treaty to commemorate the newfound peace. They have since been lost. However, two physical treaties made in the same era exist to this day: a clay tablet one in Istanbul’s Archeology Museum, and the other on Luxor’s Karnak Temple.

Articles found in the treaty mirror those of modern-day diplomacy. One article established defense diplomacy, with each kingdom promising to provide military cooperation should the other face an attack from an external enemy. A second article ensures the extradition of any political deserter to the other.

“If any great man flees from the land of Egypt and he comes to the lands of the great chief of Hatti; or a town belonging to the lands of the great ruler of Egypt, and they come to the great chief of Hatti: the great chief of Hatti shall not receive them. The great chief of Hatti shall cause them to be brought to the great ruler of Egypt,” the treaty reads.

An archaic form of diplomacy found during that time was the intermarriages between the royal families of the kingdoms; mixing royal bloodlines was considered a means of ensuring peace between kingdoms.

“And the children of the great chief of Hatti shall be in brotherhood and at peace with the children of the children of Ramesses, the great ruler of Egypt; they being in our policy of brotherhood and our policy of peace. And the land of Egypt with the land Hatti shall be at peace; and hostilities shall not be made between them forever,” the treaty pledges.

The Treaty of Kadesh is considered history’s first-ever formal peace treaty between two nations, and is highly regarded in the modern diplomatic world, as evident in the symbolic replica on display at the United Nations Headquarters in New York.

Comments (2)

[…] Treaty of Kadesh, signed between the Hittites and Egyptians in 1274 BC, is believed to be the world’s first […]

[…] Treaty of Kadesh, signed between the Hittites and Egyptians in 1274 BC, is believed to be the world’s first […]