The camera zooms in on the security man’s cigar, as he lets wisps of smoke escape. A sleek and sporty black car speeds down a road. Dressed in an elegant and sharp black uniform, he takes the cigar out of his mouth as a chic soundtrack plays in the background, conveying a distinct and stylish cinematic allure.

How, when, and why did crime films, which usually depict brutal, vicious, and cruel scenes of murder, become linked with voguish cinematography is difficult to understand. Due to its immense popularity, the film noir’s – from the French “black film” to describe a subgenre of essentially crime dramas of strikingly black and white visual aesthetic – presence in the industry endured beyond Hollywood and came to other countries like Egypt.

Though American forms of dress in crime films were heavily used in Egyptian films, Egypt’s on-screen criminals developed their own style and characterization.

Dressed to kill: The influence of fashion in crime films

One explanation as to how fashion and glamor became associated with crime films stems from the influence of photography in the criminal investigation process during the 19th century in Europe. French photographer Alphonse Bertillon, for instance, was the first to introduce a set of rules on how to take a photograph of a criminal using appropriate lighting and angles. These guidelines were then used as “proof” of inherent criminality, allowing police and security to identify patterns of whether someone was going to become a criminal through observing their facial and physical features.

When crime scene photography developed in the United States later in the late 19th century, photographs were not just seen by the police or security intelligence, but were also displayed in museums and newspapers – becoming part of the art scene. The first to introduce this was American photographer Arthur Fellig (also known as Weegee), who had his own publication of his crime scene photographs in 1945 titled Naked City, which marked the early beginnings of how the general public began to see these photographs as part of art culture.

Instead of merely documenting the crime, art historian Marketa Uhlirova notes that photography came to imagine crime, as later photographers began to imagine their own scenes and construct the identity of the criminal through the art of fashion. These aesthetic photographs were later used for inspiration, in film productions, to captivate audiences, and pull them into a dream-like world of mystery.

“Clothes are never what they seem. They always conceal, hide, create a different reality; they are used to suggest an identity that is never what it appears to be,” Uhlirova writes in her book If Looks Could Kill (2008).

Certain forms of dress in American films influenced the way audiences view the criminal. In most films, criminals are seen in crisp and expensive clothes to give the impression of dominance. Ironically, they also seek invisibility, which is why fashion is often used to conceal their identity, such as resorting to a black cloak or the classic black shades.

For the femme fatale, black tights were often worn to allude to mystery and anonymity – revealing the curves of the female body while at the same time cloaking them in a sinister black. A classic example of this was the film Irma Vep (1996), who spends most of the film dressed in a tight, black catsuit.

Gloves, tightly worn on the hands, also signified closure and anonymity, representing the “fashionable killer”, Uhlirova adds.

The Egyptian film noir

The Egyptian film noir reached its peak in the 1950s and 60s after a period of crime book fiction translation that took place in the 1890s. The fascination of Egyptians with crime also developed because of its portrayal of their frustration and anger towards the colonial legal system, and later, the widespread culture of investigators and surveillance in Nasser’s Egypt.

Early examples of crime films include Rayā wa Sakīna (Raya and Sakina, 1953). What is distinctive about this film is that it is rooted in local culture and fashion, portraying the iconic female figures in their traditional veil and costume. However, the influences of American fashion and concealment could be discerned, as the men in the film wore black sunglasses or a black eye patch on several occasions.

The atmosphere can be said to be reminiscent of American film noir with its cinematography and dramatic music, paving the way for the distinctive cinematography of the film noir.

Another example is El Wahsh (The Beast, 1954). In contrast to American gangster films, which often present gangsters in flashy clothes as a sign of success, the Egyptian gangsters in El Wash are dressed in the traditional galabiyyas typically worn by men in the villages of Upper Egypt. Nevertheless, the film also included some elements of influences from the American film noir by including a femme fatale — a love interest or female companion of the criminal — which was played by dancer Samia Gamal.

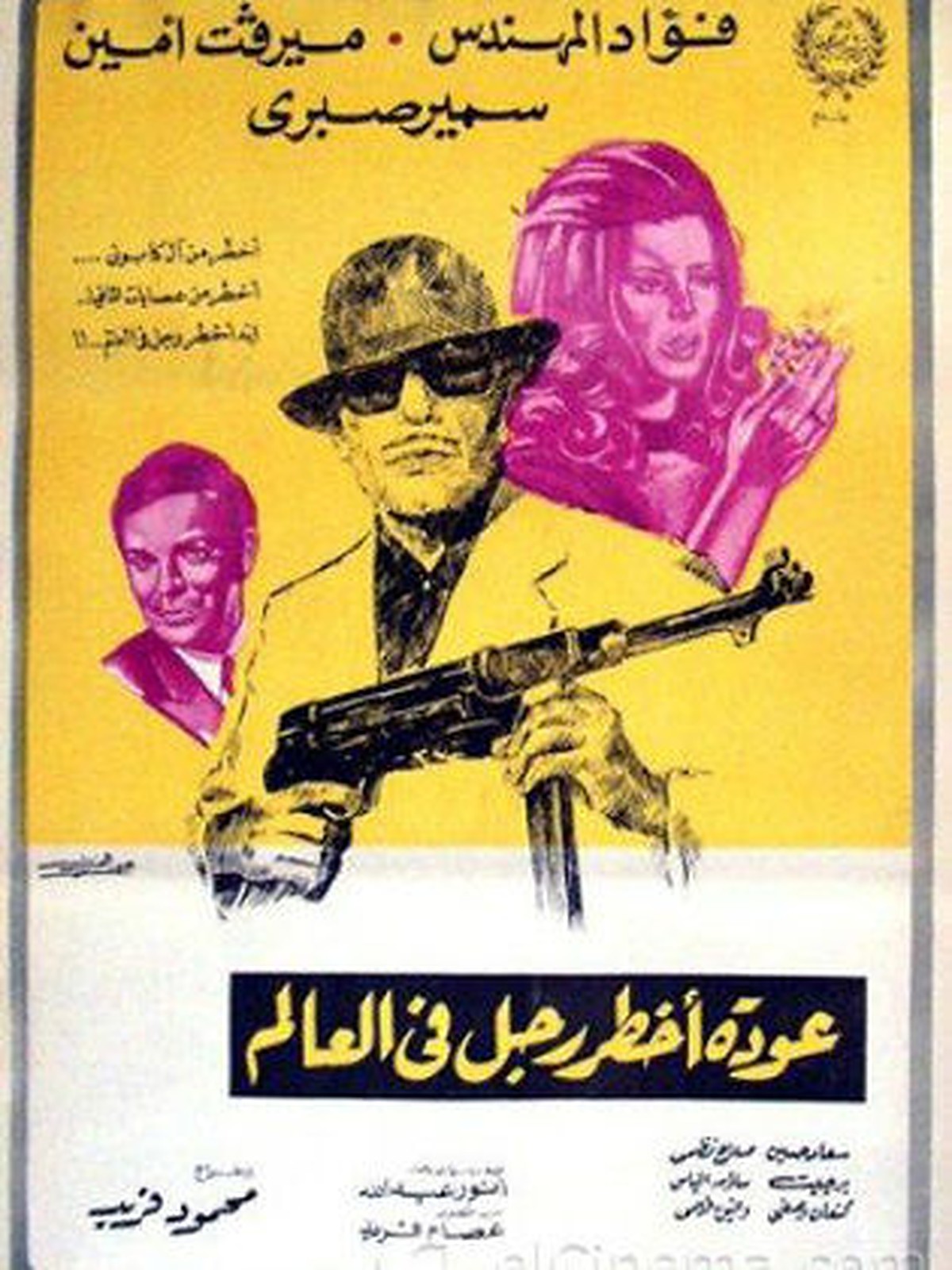

Renowned Egyptian actor, Fouad El-Mohandes, also borrows American film noir fashion influences in the crime film Awdet Akhtar Ragol Fel Alam (The Return of the Most Dangerous Man in the World, 1973). At the start of the film, he is dressed in a chic all-white suit paired with a white hat and black shades, as the wisps of smoke from his cigar escape in the air to add a dramatic effect.

The attire of women in such films is usually one-dimensional and predictable, as she is either used as decorative prop, a symbol for sex, or for violence. The fashion designers were often inspired by French or Italian modern and futuristic designs, such as Madiha Kamel in Abtal wa Nesaa (Heroes and Women, 1968) film, wearing a short, white, sleeveless cow-print belted tunic dress, paired with a white bag or mid-calf boots.

The strong association of fashion with crime is not as apparent in Egyptian films today, but there are films such as El Araf (The Knower, 2019) that draw their fashion inspiration from the past, with the female role of Maya donning a tight black suit and pants to conceal her identity.

More recently, the black suit also appears in the German-Danish-Swedish production, The Nile Hilton Incident (2017), by Swedish-Egyptian director Tarik Saleh, which has been largely regarded as a “true film noir” in the Egyptian style.

The association of fashionable cinematography with crime films does not appear to be diminishing over the years, and one reason may be that fashion has, for so many years, been used as a language to understand the criminal personality and how they used fashion to disappear and remain invisible. Yet, regardless of the disguise, sometimes the vulnerability of the criminal character is evidently shown, as clothes alienate not only them from the public, but from their own true self.

Comment (1)

[…] القاتل المألوف: كيف لبس المجرمون في فيلم نوار المصري […]