First, the cat was gone.

But it was not just the cat. Soon everything else in Toru Okada’s life pulled away the same way a star in the galaxy loses its life; the very center of the star – the core – collapses, crushing together every proton and electron.

Reality was like an ironed pale white t-shirt, before it was layered beneath other cluttered and colorful fabrics that made it no longer visible. One single event managed to radically change the neat, clean and monotonous life of Okada, revealing his powerlessness over his life, existence, and identity.

Like the star, Okada’s real, core identity was long gone by the end of the book. His inner self was corrupted and rotted by even the closest people around him, and he was no longer able to separate his own self from their own world. His own independence, and his own freedom, was trapped inside others’ reality, and before he realized, he was descending into a labyrinth of their evil and ruin.

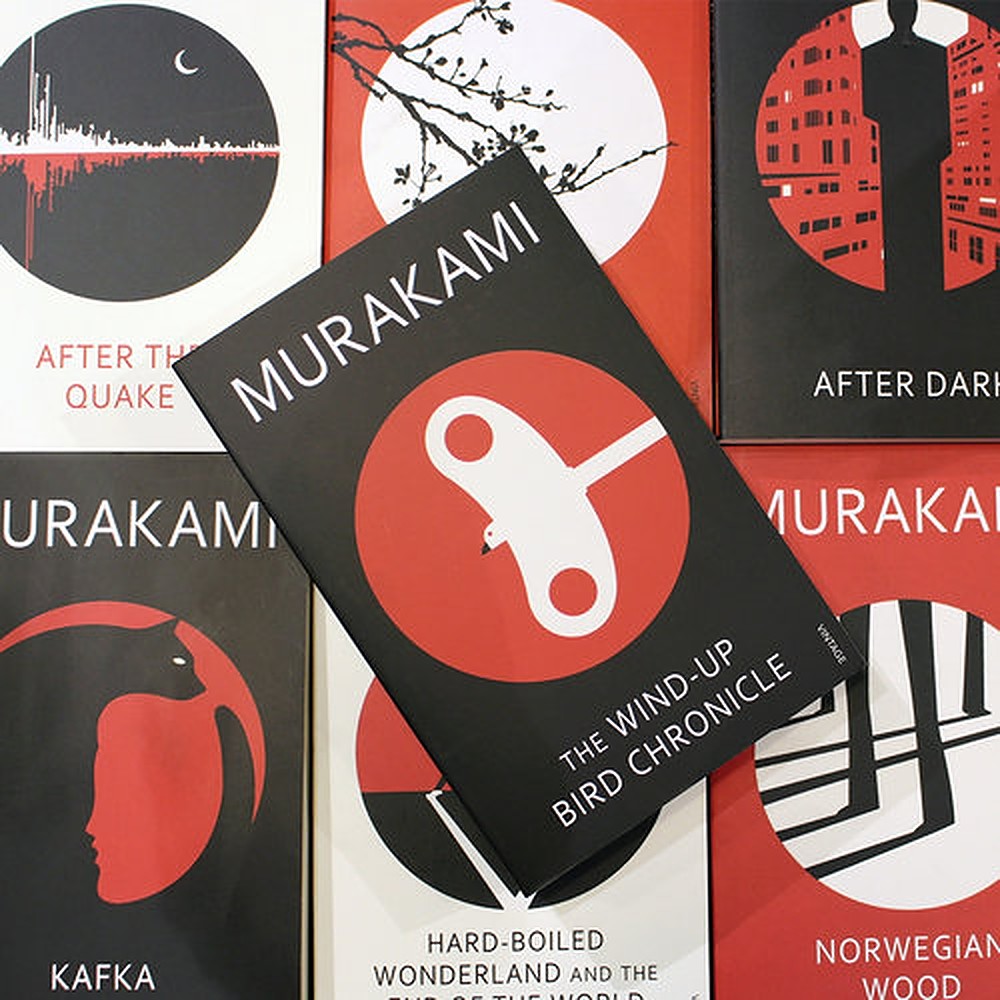

Japanese author Haruki Murakami is known for his magical realism and bizarre imagination that sets his characters off on a journey to discover not only the self, but also the mystery behind existence. What I enjoy most about Murakami’s books is that he always offers a chance for reality to turn strange, unusual and completely unexpected, but beneath the abnormality, there is also a sincere portrayal of the human inability to fully understand themselves.

Murakami’s novel, ‘The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle’ (1994), exposes the mental decay of the Japanese generation born after the Second World War, and who eventually became detached and disillusioned with the materialism and workaholism of the 1970s and, more importantly, with who they were. A generation that, like the wind-up bird in front of Okada’s house, cannot move or fly without someone winding it.

Foreign literature does not just act as a bridge for intercultural dialogue, but can also reveal social patterns and events that create room for one to critically analyze one’s own culture. Japan and Egypt may seem too distant to be culturally convergent, but a deeper look into Murakami’s novel uncovers the dangers of a politically passive society, who prefer to leave the important decisions about the future of its nation to the top bureaucrats and politicians.

Currently, on a massive economic scale, Egypt is taking inspiration from the East Asian and Chinese economic miracles, which saw low and middle income economies rapidly develop into high-income economies in the late 20th century. The success is often attributed to government policies and leadership above anything else, and empowers the argument that political participation can hamper economic development. However, literature can provide an alternative viewpoint to explain the hidden ills and drawbacks of such an economic model, and how developing nations like Egypt can avoid falling in that trajectory.

In the postwar era, particularly between 1970 and 1979, the Japanese population became less interested in politics after the popular uprising against the US-Japan Security Treaty was defeated. Instead, its citizens became more concerned with climbing up the ladder of social status and wealth, which was popularly used in media and advertising slogans stating “my car-ism” (my car) and “my home-ism” (my home).

Against this context, Murakami explores the thread of pain that connects three generations together, from the ones who have directly witnessed trauma and political conflict, to the ones that have given up on any kind of political participation. Participation in modern society comes only through material means, and only if one has a lot of wealth and power is regarded as worthy of participating. The rest, who are unable to acquire wealth and thus are not able to participate or belong in society, fall behind.

In his novel, a new Japanese generation, which did not understand the real challenges of survival and the efforts of the previous generation, was also unable to find a strong identity through an easy and well-off lifestyle that was offered to younger Japanese folks by their parents and grandparents. Consumed by a soulless and materialistic lifestyle, all while becoming too dependent on the people around them and the political system, the characters in Murakami’s novel turn towards the supernatural in an attempt to search for a sense of identity.

Rather than face reality and open up to the world, Okada chooses to lock himself up in an imaginary world; a dark maze-like hotel where “room 208” represents the heart of his entire being. Finding comfort and safety in his parallel reality, Murakami’s novel unmasks the true loneliness and unhappiness of his own generation, who have only found survival through allowing the fantasy to co-exist with the real.

Though it was published in the mid 90s, the novel provides a glimpse of the prospects of a grim future for younger generations who have become passive and apolitical for years. When political participation takes a backseat in favor of the pursuit of economic development, this risks a new wave of alienated youth who are struggling to belong in society through meaningful ways. Estranged and isolated, they fall into the hidden ‘unreal’ side of a hyper-capitalist society, which is defined by the difficulty to find the essence of one’s identity as they are constantly provoked to consume.

Okada’s own life can be seen through an Egyptian lens. He acts as a powerless nonentity who has no position in society, and who has no power to change his life or his surroundings. These existentialist elements in Egyptian society were highlighted by Egyptian philosopher Abdurrahman Badawi, who shared the anxieties of the younger generation, traumatized by colonialism and political struggle, and their overwhelming sense of powerlessness.

This is also echoed by the novel, ‘Beer in the Snooker Club’ (1964) by Egyptian author Waguih Ghali, who documents the existentialist crisis of Egyptians that lived after the fall of colonial rule. Country clubs, lavish parties, and a lazed out lifestyle consumed by materialism eventually made the characters feel lost and powerless about their political quests, and ultimately, their personal identities.

While in Japan there is a sense of powerlessness following the traumas of the Second World War and the tragedy of the Hiroshima bomb, in Egypt, political alienation have made the possibility of realizing one’s true potential seem nearly impossible.

Following the 2013 revolution, as well as political turmoil and economic crises, Egyptians were willing to accept a new social contract that prioritizes political stability and economic prosperity, yet this could undermine feelings of citizenship if an inclusive political dialogue is not created. Earlier in July, President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi announced that a national dialogue is taking place, yet it remains unclear as to how many of the dialogue’s participants will be common citizens and not merely political and economic elites.

Modern Egyptian writers like Ahmed Naji, Mohamed Salah El Azab, Hend Jaafar, and Hatem Hafez explore how Egyptian society has managed to cope with its realities after witnessing two intense transformations in history – the January 2011 revolution and the July 2013 revolution.

The writers reflect a city (Cairo) that is yet searching for an identity. Some are searching for it while dozed off, preferring to turn to their dream-like romances, soap opera, football, or drugs, while others have become too frustrated with the search, resorting instead to anger, force, torture, or madness.

Like Murakami’s Okada, who begins to descend into the darkness of his dysfunctional family rather than achieve his own freedom, Egyptian characters in certain short stories and novels, such as ‘Into the Emptiness’ (2018) by Hassan Abdel Mawgood and Temple Bar (2015) by Bahaa Abdelmegid, eventually lose their mercifulness, forgiveness and humanity, and become more resentful of the people around them and their flawed characteristics.

Comments (0)