In a family car roaring down a European highway, an Egyptian couple inserts a USB drive into a black adaptor that screams 2010. In the backseat, two teenagers sit, each looking out of their own window.

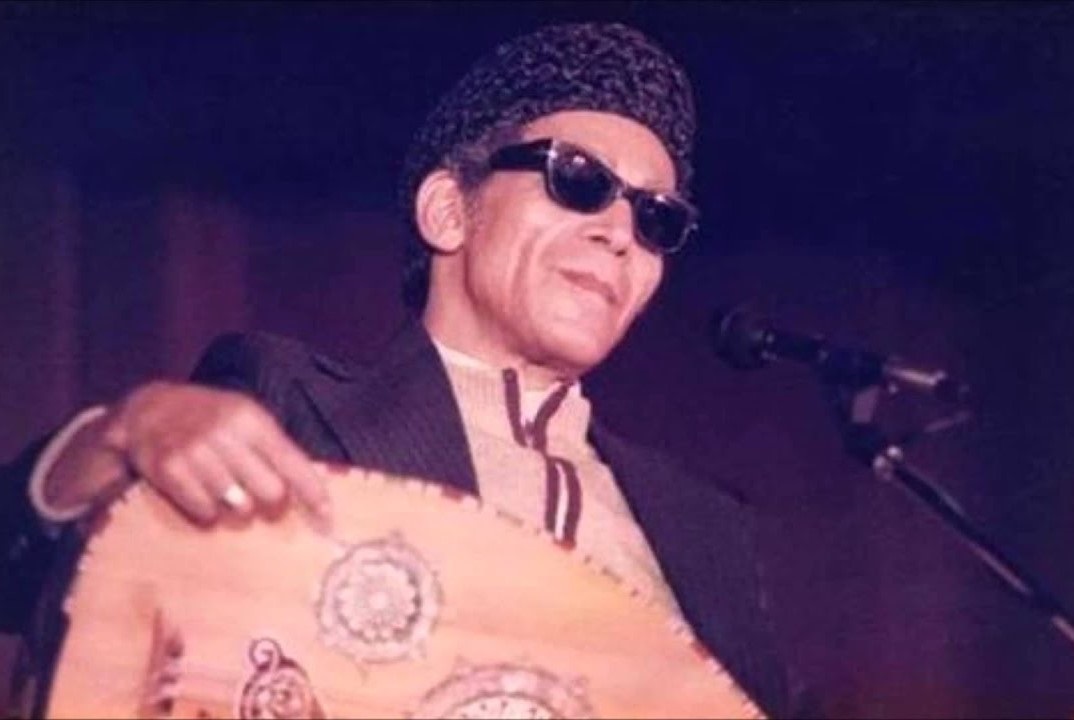

A scratchy sound emanates from the car’s speakers, a few preparatory strokes on a oud, and the deep voice of a man clearing his throat.

This was how my brother and I were first introduced to El-Sheikh Emam.

A musician, revolutionary artist, and Egyptian icon, Emam Eissa – known far more commonly as El-Sheikh Emam – holds a special place in my family’s collective heart. From intimate, live musical performances at my grandparents’ Maadi home in the 1970s, to sentimental listening sessions at my aunt’s West London apartment with my 24-year-old cousin in 2019, Emam has been a constant in my family for far longer than I have even been alive.

From al-Kuttab to University Halls

Born in 1918, Emam’s circumstances were as humble as could be. Egyptian researcher, writer, and friend of Emam’s during his lifetime, Kamal Mougheeth, tells Egyptian Streets that Emam suffered an eye infection at a young age, and much like Taha Hussein before him, his parents’ attempts at alternative healing left him blind for the rest of his life.

Living in poverty in his childhood and youth after being estranged from his parents in 1934, he spent much of his time in al-kuttab (Qur’an recitation lessons in mosques), memorising the Holy Qur’an in its entirety, earning himself the title of Sheikh he later became known by. He began to learn the maqamat (musical keys that guide Egyptian and Arab tunes), reciting the holy words melodically as was customary in Egypt.

“In the 1920s, Egypt was more welcoming of life, there was more cultural variety,” Mougheeth says. “Sufism was rife at the time, and he let it influence him.”

As he grew older, people began to notice his vocal talent and immaculate ear for music, and he was encouraged to engage with music outside of the context of religious recitation. He began to learn the oud, and started out singing songs of legendary Egyptian composers such as Sayyed Darwish.

For years he developed his musical talent and his memory of steel – for a time, and until a falling-out, as the apprentice of Zakaria Ahmed himself, another monument among Egyptian composers and one of the musicians who made many songs for Umm Kalthoum.

The 1960s were a turning point in Emam’s musical career. Mougheeth says that it was in those years that he was first introduced to a group of leftists that had just been released after being imprisoned during the time of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel-Nasser, and as he learned more about the movement, he gradually became an integral part of it.

He met the late poet Ahmed Fouad Negm in 1962 and a prolific and dazzling musical partnership was born. With Negm’s acerbic and razor-sharp lyrics and Emam’s novel yet quintessentially Egyptian music and emotive singing voice, they built a repertoire of rebellious, humorous, and heart-wrenching songs.

The 1970s were Emam and Negm’s first heyday. At the time, Egypt was experiencing political protests and uprisings calling for social justice, with young people at the vanguard. During that time, the duo would go to universities around Cairo, performing songs and reciting poems that riled up young leftists’ revolutionary spirit, and emboldened them in the face of their struggles. It was during those years that Emam was first introduced to jails and the authorities’ retribution.

That same decade is when my family’s story and Emam’s converged, starting with a group of my paternal grandparents’ friends. They were four couples, each with their own taste in music, and each with their own political leanings, but tied together through lifelong friendship and a keen interest in the arts.

Among them was a couple who were staunch leftists, and got to know Emam personally through their political group, becoming friends with him, and sometimes even supporting him in the struggles he faced as a disabled man living alone in the Hosh Adam neighbourhood of Cairo’s Al-Azhar area. After this couple introduced the group to Emam, they began to take turns to invite him into their homes and listen to his latest songs and compositions.

El-Sheikh Emam was invited to my grandparents’ home not only as an entertainer, but as a guest, a friend, an exciting conversationalist, and a lively joker. My grandfather tells me that when he came to visit them, he did not bring his oud up from the car unless he was specifically asked to, as he never wanted to impose.

But once he took hold of his instrument he would be like a man possessed. After a few bars in the right key and a clearing of his throat, he would lose himself entirely in the song he was playing.

If it was a satirical one like Sharraft Ya Nixon Baba (It’s Been an Honour, Father Nixon) or ‘Valery Giscard d’Estaing’, his wry smile would be audible in every word. If it was a fiery song like Etgamma’o El ‘Oshaq (The Lovers Gathered) or Shayyed Qosourak ‘Al Mazare’ (Build Your Palaces on Farmlands), his defiance would show in every syllable he uttered. And if it was a heart-wrenching song like Guevara Mat (Guevara Is Dead), he would shake with grief that could only be his own.

And his little audience, my grandparents, my father, my aunts, and their friends would find themselves singing along with great gusto.

An Immortal Legacy

My family’s connection with El-Sheikh Emam continued into the 1980s, when my mother and father, two young diplomats, were introduced to each other at work and began to discover unexpected shared interests.

“Emam was more clandestine when we met. Fewer people knew him,” my mother tells me, as by then, Emam was only known to intellectuals, students, and workers, but not so much to the average Egyptian. “So when we discovered that we both liked him, it brought us together.”

Both carrying memories of his revolutionary music since their adolescence, they exchanged cassettes at first, and later, when they were married and on their first diplomatic mission together, they attended a concert of his in 1991 in Belgium. To their delight, the audience was singing along with great enthusiasm despite not being Egyptian for the most part, but overwhelmingly from other North African countries.

I was only two years old when Emam passed away in 1995, and still a decade and a half shy of my introduction to his music. But his death meant neither an end to our family’s love for his music, nor did it mean the death of his influence on politically engaged Egyptian youth.

When the Tahrir sit-ins of the 2011 Revolution began, I saw in real time a revival of Emam and Negm’s revolutionary songs, giving Emam a posthumous second heyday. Congregating in the square, young people would form circles around those skilled with a oud and sing many different songs, such as Masr Yamma Ya Baheya (Egypt, O Beautiful Mother), deriving hope and strength from its unforgettable melody and powerful words:

”مصر ياما يا بهية يام طرحة وجلابية

الزمن شاب وانت شابة هو رايح وانت جاية

جاية وسط الصعب ماشية..فات عليكي ليل ومية

واحتمالك هو هو وابتسامتك هي هي يا بهية“

“Egypt, o beautiful mother, in your veil and galabiyya

Time ages while you remain young, it fades while you approach,

Approaching, wading through the strife,

Going through one hundred and one dark nights,

Yet your endurance stays the same, and your smile remains the same.”

Musicians and bands were inspired by him, most famously Eskenderella, a band whose repertoire was to a large extent made up of covers of his songs. Other smaller bands named themselves after some of his classics, such as Baheya.

Stuck abroad with feelings of mingled hope and anxiety, my brother and I needed something to bring us closer to Egypt during the days of the Revolution and the years that followed. I remember the day my brother sat me down beside him at his desk and played Etgamma’o El ‘Oshaq for me to listen to for the first time.

“.والشمس غنوة من الزنازن طالعة ومصر غنوة مفرّعة في الحلق”

“And the sun is a song out of the dungeons rising,

And Egypt is a song that blossoms through the throat.”

The song’s powerful message of defiant hope in the face of repression made it one of my favourites in his entire repertoire until today, and the moment of wonder I experienced upon first listening to it is engraved in my mind; it brings tears to my eyes even as I write about it a decade later.

Emam’s songs presented to us a love for Egypt that was not expressed in clichés, in tired metaphors about the Nile, or in recounting the glory of battles we had not been alive to witness. He spoke of timeless, unaffected love. He did not gloss over the suffering or the injustice, but neither did he let those things get in the way of his rejection of oppression, or make him relinquish his love for Egypt and his faith in its people deserving better.

My father, my grandfather, and Mougheeth all separately emphasised how elemental this authenticity was to their love, and the love of many hundreds of thousands of others for his music. It is what let my brother, my cousin, and me inherit the love our parents and grandparents cherished for Emam and his music, despite its emergence long before our time.

Even as I brought up my intention to write this piece about Emam at a family gathering, a number of us spontaneously burst into song, choosing a classic whose lyrics, written by Egyptian poet Naguib Sorour, were inspired by Egyptian folklore: El Bahr Beyedhak Leih? (Why Does The Sea Laugh?)

“يا قلة الذل أنا ناوي ماشرب ولو في المية عسل.”

“From this flask of indignity I resolve

Not to drink, even if the water is laced with honey.”

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (0)