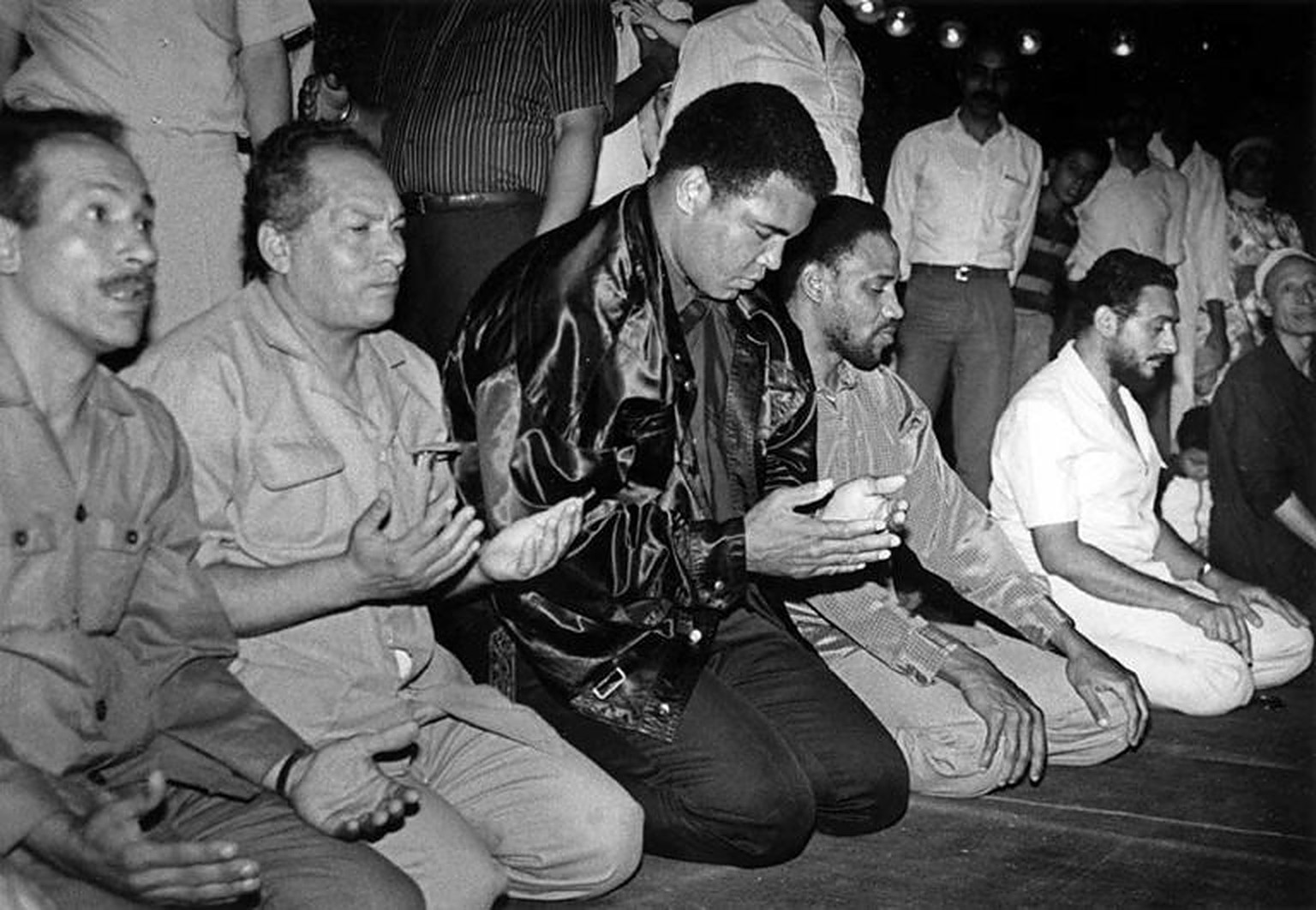

The full moon breaks through the skies of Siwa and pours a beaming light over a crowd of Sufis, who absorb the serenity of the sight to soothe their soul. To reach this kind of serenity for five minutes a day is a rare achievement for many, but through just one photograph, it can extend to a lifetime.

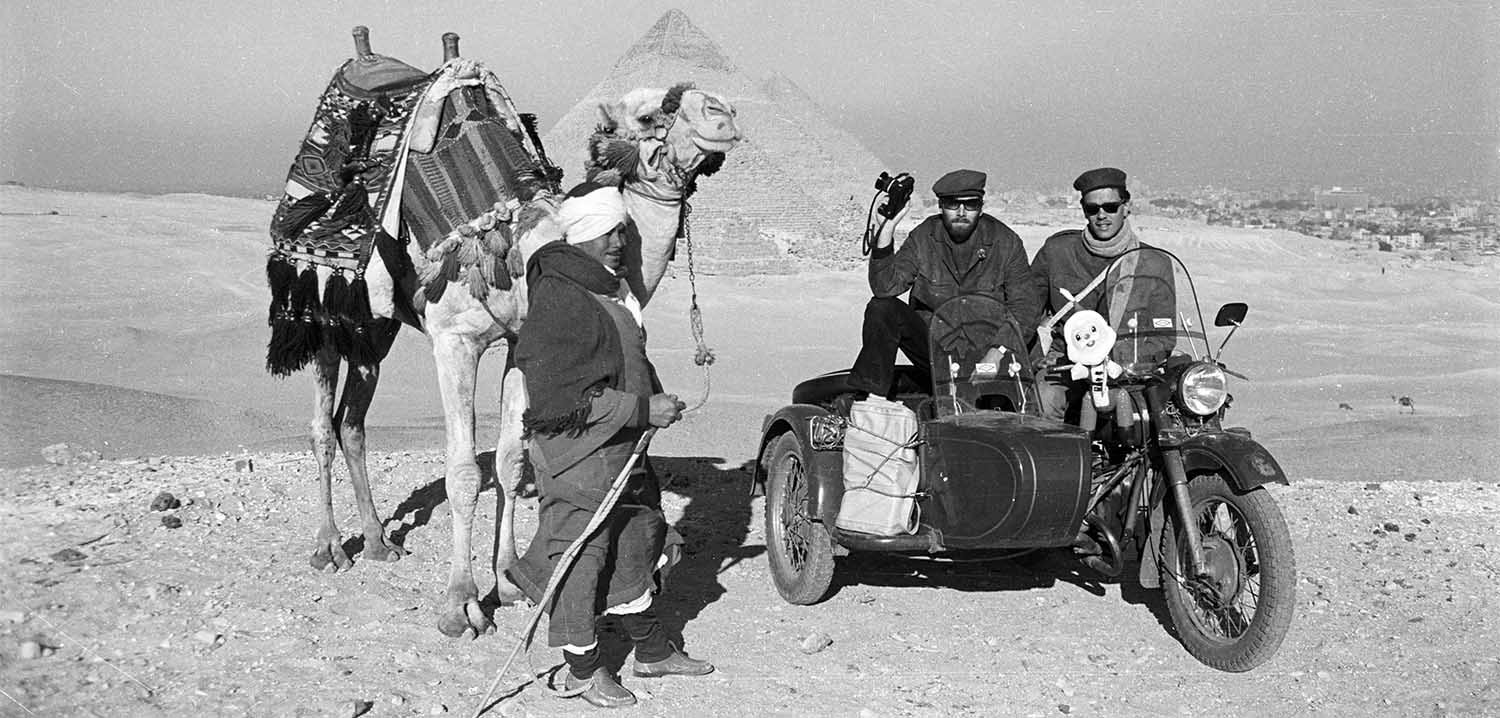

This photograph was captured in 1994 by one of the most prolific news photographers in the Middle East for over 30 years: American-born Austrian photographer Norbert Schiller. Working for notable news outlets such as Agance France Presse (AFP), the Associated Press (AP), the European Press Agency, and the New York Times, Schiller has covered everything from conflict, politics, insurgencies, as well as street and travel photography.

The underlying motive behind all of these photographs was not to define Egypt in a particular way, or ask any questions about why or how it is the way it is. It was much simpler and more modest; it was a fondness for the place and the people.

“For me, Egypt became like a love affair. I really wanted to be there. It wasn’t like I was sent there,” Schiller tells Egyptian Streets. “I fell in love with Egypt the minute I arrived, because it is one of these countries that is very dynamic. It’s a country of contrasts. You have the ultra-poor, the ultra-rich. You have the impoverished and you have the educated. You’ve got everything there. That’s the craziest thing about Egypt.”

His journey to Egypt began in 1979, when Schiller was still in his first year of college. After years of moving around between Europe and the United States of America, he grew tired of the polished and hyper-stylized streets that often try too hard to impress. “I wanted something a little bit more,” he shares. Soon immediately, he hopped on to a plane with three of his friends to Cairo.

The defining moment

Arriving in Cairo on a chilly February evening at 11:30 pm, Schiller took the bus from the airport to Tahrir Square. He checked into a small hotel called the Golden Hotel, and before he could take time to rest, he was taken aback by the bustling energy in the streets. It was then that he realized that Egypt never tries hard to impress; it leaves the eye to wander freely to see everything that is ugly and beautiful.

“I remember it being midnight and how crazy the streets were. It was just packed. Everybody was out and the juice stands were still going, and there was plenty of street food,” he says.

The story of how he became a photographer was not the usual story of picking up a camera from a young age and then developing a passion for the profession over the years. Instead, it began with a chance encounter with a stranger and a bag of peanuts.

“I was in my hostel in Cairo, and I remember somebody came to give me a bag of peanuts, and I asked, what’s this for? And then he told me that Jimmy Carter, my president, will be coming tomorrow,” he says. “For some reason, I remember feeling so desperate to take a picture of Jimmy Carter and Anwar Sadat.”

On that day, the scene was unsurprisingly chaotic: a tsunami of a large crowd was spread out across Tahrir Square, while police guards were standing in every corner to block the distance. Standing in the middle of the crowd, it was impossible for Schiller to take the photograph, but in the middle of such mayhem, he was able to keep his cool and make a small request from one of the officers standing guard.

“I told him, listen, please, I really want to take a picture of my president next to Anwar Sadat. Is there any way I can just stand in front of the police line?” he recounts.

“He said something to one of the police guards, and then the police walked me out into Tahrir Square away from the crowd and told me to sit. I sat there cross-legged in Tahrir Square for about an hour, waiting, and then I began to hear the sirens and the entourage leaving the parliament. I had an old camera and took three frames, and in that frame, I have one picture of Anwar Sadat and Jimmy Carter looking at me with their hands up.”

Even though he was not a journalist at the time, it was at that particular moment that Schiller fell in love with news and of trying to capture a moment, which later sparked his lifetime career as a photojournalist.

“What I learned in Egypt as a photographer helped me photograph the whole region. I learned how to manipulate my way through crowds of people or when the police are shooting or anything chaotic like that. All of these things that I learned in Egypt helped me when I was covering Somalia, Ethiopia, the Gulf Wars, the Intifada, and Palestine,” he says.

Donkey rides and busy trains

Exploring Egypt on donkey-back, Schiller traveled across the villages along Upper Egypt alone to capture the pulse of Egypt’s streets. Through his vigilant eye, his photographs depict the small and ordinary moments that are often excluded from photographs, but carry the spirit of the everyday life of an Egyptian. From the small kiosk that sold tea, to the hassle inside a train ride, Schiller realized over the years that the best approach to picturing Egypt is to not look like a photographer or a journalist but to blend in with society.

“It’s becoming more difficult to work as a journalist, so it’s best to lay back a little bit and blend in with the crowd,” he says.

“I didn’t have many problems working as a photojournalist in the past. We were invited to a lot of governmental events and I had many personal encounters with former President Hosni Mubarak. You were sort of looked at as a non-partisan when you had a camera or you were a journalist. But now it’s different, and not just in Egypt, but also in the United States. Journalists are now considered to be a real threat.”

In recent years, photographers have experienced many difficulties working in Egypt and were often prevented from taking any photographs that tarnished the image of the country. This year, foreign vloggers shared their frustrations on social media about being stopped from taking photos and videos, and their camera equipment being confiscated.

In July of this year, recently replaced Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, Khaled El Anany, announced that street photography will no longer require permits, but only for tourists and residents. Photojournalists working in news agencies, however, would be required to obtain permits through the State Information Service. The ministry’s statement added that it is forbidden to take or share photographs of scenes that can “damage the country’s image”.

Schiller’s experience as a photojournalist in the past presents an important lesson for photographers and journalists today: learning to go beyond the urbanism and rapid construction currently happening, and instead, to be more patient and adventurous.

“Egypt has definitely changed a lot. I really feel that the image of the Gulf is influencing all of these grand projects that we are going to see, like the New Alamein or the New Capital. People will be photographing these new cities with tall skyscrapers, which will not look like the Egypt I know,” he says.

“You’ll have to really go out of your way to see Egypt, like going into the countryside, because I don’t think people really want to see tall skyscrapers anymore, I think we’re done with that. What people are really looking for nowadays is more nature, and architecture that is more environmentally-friendly. I don’t think that skyscrapers are the answer.”

Schiller also adds that, in the past, patience was a photographer’s strongest trait. In the rapid age of social media, there is little room for journalists to appreciate the art of photography and the process that comes with it.

“Things have become too rapid. In the past, I had to develop the film. I had to make a print, I had to scan it on a drum scanner that was in the office. Or if I was in a hotel, I had to hook it to a telephone line. It was a very slow process. I mean, sometimes it took me an hour to get one photograph out,” he says.

“We had incredible patience as photographers, and I don’t think photographers today have the patience that we have. I think that we appreciated photography much more back then because it was so much harder to take and you didn’t see the results right away. You had to wait.”

To encourage young photographers to reframe the narrative on Egypt over the last ten years, Egyptian Streets is announcing an open call for photographers to participate in the exhibition “Egypt: 10 Years Later” which will be held in October 2022.

This exhibition will narrate the incredible transformation Egypt has undergone over the decade, as the most populated country in the Middle East, and one of the oldest in the world. Egypt has undergone a monumental shift, becoming more complex and transcending the identity of Egypt as we have always known it.

Revolutions, progress, demographic changes, increasing connections, the advent of globalization and the impact of climate and the economy have created a new, yet liminal, country, one that is in the process of being birthed while still keeping the vestiges of its past.

The aim of the exhibition is to use photography – be it conceptual, documentary, abstract or any genre – to share with others the evolution of Egypt from 2012 to 2022 and to digest its changes, leaving room for discussion as to where, who, and how it has become.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (0)