As a young girl, digging inside my mother’s purse everyday was a rehearsal to adulthood. Sitting cross-legged in a chair, I would pick up the rolled glossy magazine from her bag and imitate the older women I saw at the hair salons, flipping through the photographs of Egyptian and Arab celebrities as I took a bite out of my favourite snack.

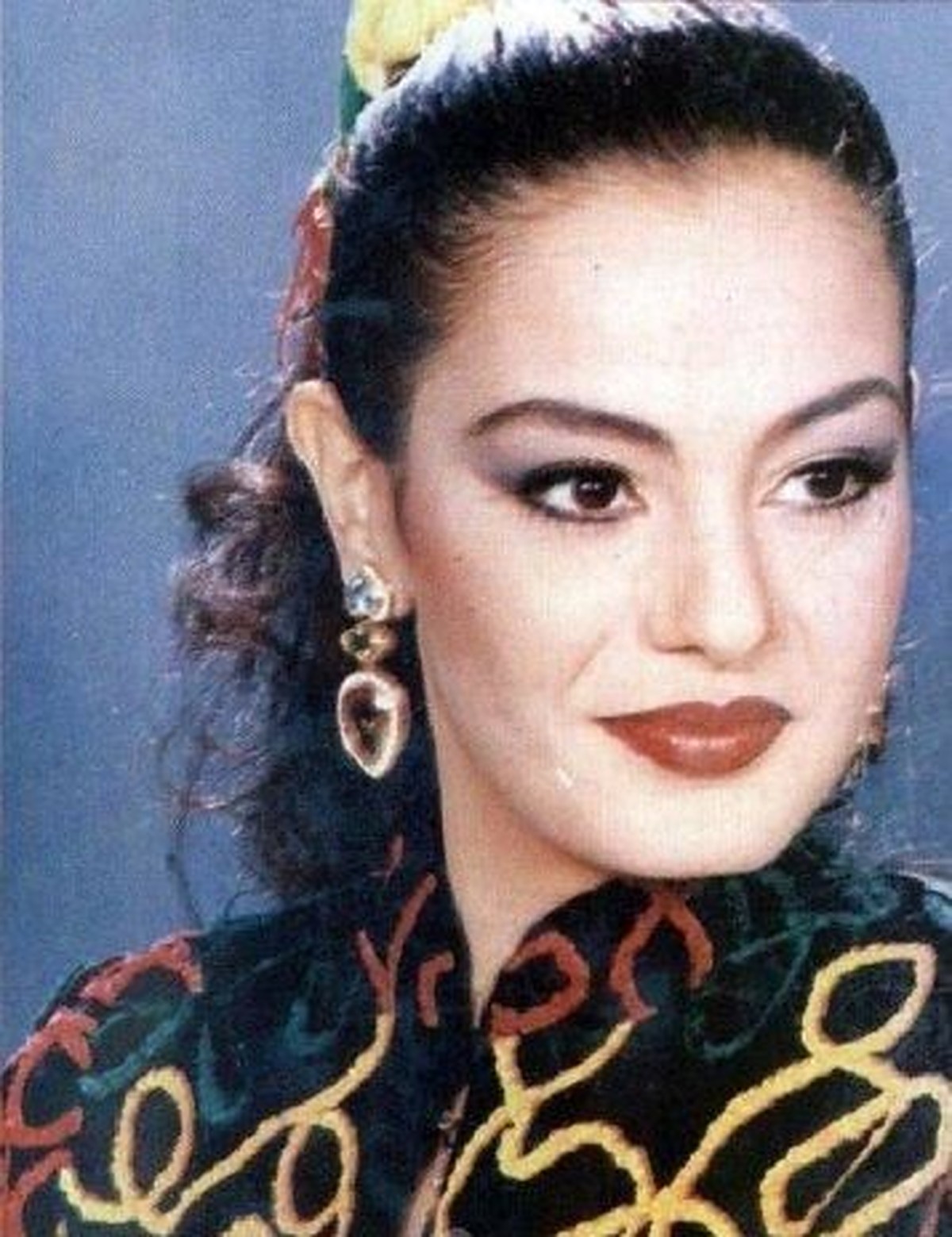

From Hala Shiha and Menna Shalaby’s overlined brown lips to Nancy Ajram’s thin brows, Arab women’s makeup techniques stood out from other women. At the time, the colour brown was a staple in nearly every Arab women’s makeup bag. Every time I wear brown today, vivid memories of my grandmother’s makeup looks come to mind—soft hues blended smoothly on her eyelid, paired with a pigmented brown lip liner that epitomizes her strength and sophistication, which creates a luminous contrast between her olive skin and the dark lip.

However, growing up as a teenager in a highly Westernized culture, the colour brown was never popularized or valued as it was in my Arab households. Instead, the bubblegum pink lip shades, which matched the rosy-cheeked complexions of white women, were seen as the ideal standard of beauty. The school bathrooms were packed with girls comparing and sharing their berry lip glosses, imitating women in magazines such as Cosmopolitan and Seventeen, with their sheer lip glosses.

For years, top beauty brands imported into the region rarely included a richer palette of shades to suit all complexions, such as Black, brown and olive skin tones. Women in the global South had to create their own shades by using brow pencils to shape their lips, or applying henna dye directly on their lips or eyelids. For my grandmother, applying the henna dye as part of her beauty routine was akin to religion, as there were little alternatives to help her reach the brown aesthetic she had always loved.

Yet, when it comes to credit for the beauty trend of the lip liner, women in the global South have often been excluded from the narrative. They are simply not deemed valuable enough to be part of the conversation. Most recently, the revival of the dark brown lip liner look has been attributed to a 1990s and 2000s nostalgia, rather than the Black and Brown women who pioneered the look. Instead, beauty articles often reference famed celebrities such as Victoria Beckham, Jennifer Aniston and Jennifer Lopez for popularizing the trend in the 90s.

According to beauty and culture writer Thalia Henao, the dark lip liner grew out of Black neighborhoods in the United States out of necessity in the 1940s, because there were few brands making lip products in shades that suited darker complexions. This look was later embraced by young Mexican-American women, who used the dramatic look as a mechanism to stand apart from other women. Henao notes that this esthetic laid the groundwork for the 90s look of the dramatic eye makeup, baggy clothes, and bold overlined lips.

In a recent TikTok video, Latina creator @benulus shared that she has been wearing the dark liner regularly, but often received criticism for it, showing screenshots of comments calling it an “ugly lipstick.” Rather than celebrating the beauty culture and unique styles of ethnic women, the beauty industry often does the opposite: it appropriates their trends for profit, without adequately giving credit to origin.

While female celebrities in the West boost their style persona off these beauty trends, women from the global South are either excluded or ridiculed for their own looks and cosmetic choices. The most visible example of this is on TikTok, where the “clean girl aesthetic” – characterized by slicked-back hair and gold hoops – which has long been worn by Latinas and Black women, is now rebranded and gentrified as looks inspired by white women for white women. The brown lip liner has also been rebranded as a “glazed brownie lip” look worn by mostly popular female celebrities, without any credit given to Black, Latina, or Brown women.

Similarly, the appropriation of Arab women’s looks dates back to the 20th century, when the dark ‘kohl’ eyeliner came to be more associated with women’s beauty and fashion after German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt in 1912 discovered the bust of ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti in Amarna. Historians state that this pushed a large trend of dark eyeliner into the 20th century to mimic Nefertiti’s beauty. However, by the 1960s and onwards, makeup brands such as L’Oreal and Maybelline rebranded the kohl as a “rock’n’ roll” edgy esthetic made to resonate with pop culture at the time, excluding ancient Egypt from the narrative.

There is little coverage online about Arab women’s appearances, but in contrast to the glossy magazines at the time, which were only sold to an exclusive number of people, social media provides room for Arab women, Black women, Latina women and all other women from the global South to speak about their beauty in a way that is entirely unique to them.

Comments (3)

[…] occidentales et des magazines populaires également Mode. Détenir qu’il existe un casier Un tas de mode Et les humeur qui sont venues des communauté du Sud ont continuellement été pointées du […]

[…] famous Western celebrities, and popular publications such as Vogue. Though there have been a handful of fashion looks and trends that came out of the global South, these were often appropriated and seldom […]