“El Ghorba was an indirect reason that led to my divorce,” says Amr Alaaeldin, a 35-year-old Egyptian engineer based in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

‘El Ghorba’, which loosely translates to ‘estrangement’, is a term used to describe living in a country other than one’s own.

More than five million Egyptians work in the Arabian Gulf — with Saudi Arabia accounting for the majority of Egyptian immigrants. Between the 1960s and 1970s, as Egypt’s population increased and its economic situation worsened, many Egyptians began relocating to the countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC); the latter consists of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and UAE. With a rising demand for labor in the GCC, Egyptians sought better job opportunities and improved living standards. Unfortunately though, many who emigrated without their families found themselves facing strained familial and romantic ties.

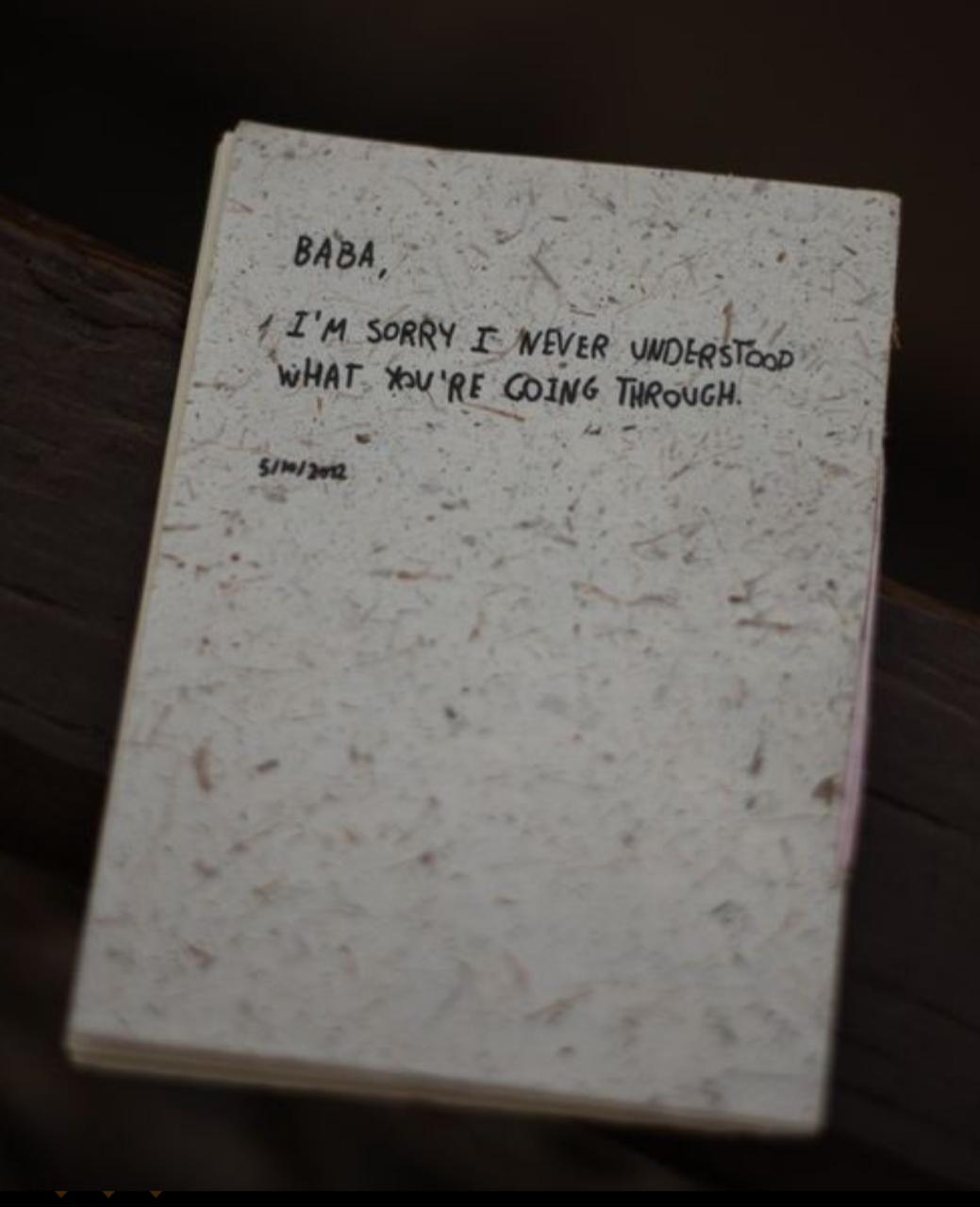

In September, Egyptian anthropologist Farah Hallaba launched “Being Borrowed”, a collaborative creative project that addresses Egyptian migration to the Gulf. Stemming from her belief that this experience is “underrepresented and understudied”, the multi-output collective attempts to tackle temporality, family dynamics, belongingness and more, through personal narratives.

Broken relationships and grappling homes

When Alaaeldin first traveled to Saudi Arabia for work, his wife accompanied him. After only a year, he realized that it would not be financially feasible for her to remain with him. Between delayed salaries and increasing expenses, Alaaeldin decided it is best for his wife and their newborn to go back to Egypt. Two years later, the gap between the couple grew and divorce was the ultimate result.

Like Alaaeldin, Mohamed Hasan, 48, recalls that when he was graduating in 1998, it was a common phenomenon for ambitious people to leave Egypt in search of higher salaries, improved living standards, successful careers, and stability upon retirement. According to him, no one planned on working in Egypt post-graduation.

Hasan, who currently resides in Kuwait and works in healthcare administration, traveled to work in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia at two different points during his career. In 2000, he traveled there for the first time, only to return to Egypt in 2006. He decided to travel again in 2009, and came back once more in 2011 hoping for brighter financial opportunities in Egypt post-revolution. He was disappointed to realize that Egypt’s economy had only taken a plunge, prompting him to return to Saudi Arabia.

As a father of two, Hasan admits that his relationship with his son and daughter was definitely affected by long-distance.

“I have a relationship with [my children] till today, but it’s not very strong. Sometimes, sadly, I feel that it is slightly financial[ly driven],” Hasan explains.

From his experience, Hasan strongly believes that long-distance relationships do not work.

Through phone calls, video calls, and instant messaging, many fathers attempt to maintain and nurture the bond between them and their children. However, only few manage to do so.

Many struggle to live independently of their families, and despite their attempts to adapt, they often fail. Nevertheless, returning to Egypt is rarely a viable option.

“Any husband who lives away from his wife or children, it either ends up with separation or divorce, and an ailing relationship with his children, or his entire relationship with the family just becomes cold; he becomes like a visitor to his own house,” Alaaeldin tells Egyptian Streets.

Despite the struggles, Alaaeldin would still choose to emigrate in hindsight — but this time together with his family.

“I initially planned on traveling for five years. But I had no idea that my father would pass away, and that my financial responsibilities towards my family would increase, health emergencies would come up, etcetera etcetera,” Alaaeldin says.

Opportunities and priorities

Similarly, Adel Botros, who worked for several years in Qatar, initially planned on living there for a maximum of two to three years. Currently retired and based in Egypt, Botros remembers that the hardest part of being away was not seeing his daughter grow up.

“Life in the Gulf is very expensive so it was not practical for my wife and daughter to live with me when I traveled,” Botros adds.

“Although I definitely wished to have been able to live with my daughter here in Egypt, if I had stayed, I wouldn’t have been able to offer [my wife and daughter] the life they lived or give my daughter the opportunity to do her Bachelors in Canada and her Masters in France,” Botros tells Egyptian Streets.

Oftentimes, many men travel to the Gulf with plans of staying two to five years, hoping to make a sufficient amount of money to go back to Egypt, buy a house, and start a private business.

Having said that, not all who travel do it willingly — some are forced.

Emotional struggles; between fathers and children

Maged Atta, a 57-year-old financial manager, never intended to travel; but when the company he was working for opened a new branch in the United Arab Emirates, he was forced to move. Still, he planned on remaining for three years before returning to Egypt. However, given that the company was still in its infancy, Atta and his wife decided it was too much of a risk to move the whole family there.

To compensate for not living together, Atta’s wife and two daughters spent their summer and winter vacations with him, and he used to travel to see them as often as he could.

Even though Atta is grateful for his family bond, which he describes as strong, there were many tough days as well.

“My elder daughter once told me that she’s emotionally tired of welcomes and goodbyes,” Atta remembers. “When she got older, she told me that she and her sister used to cry themselves to sleep and hide that from their mom because they knew she was under the pressure of raising them on her own here in Egypt.”

It is common practice that when one member of the family is living abroad, the rest of the family hides from him or her any shortcomings taking place, health emergencies, so as to not make them worry.

This was the case in Atta’s family; he was never told about the emotional struggles that they were facing. On the other hand, there were times when he, as a father, was struggling alone.

Despite the fact that traveling comes with its own set of challenges, many Egyptian men continue to choose working in the Gulf over trying to make a living in Egypt.

With a struggling economy, a continuous devaluation of the Egyptian pound, and Egyptians suffering from constant price hikes, migration to the Gulf will probably continue, if not increase, in the next few years, even if that means breaking family bonds and ruining households.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (2)

[…] Between Divorce and Hardship: Stories From Egyptian Men Working in the Gulf […]

[…] Between Divorce and Hardship: Stories From Egyptian Men Working in the Gulf […]