Unrelenting and unforgiving is the Arab experience. From wet womb to war-torn, Arab children are born into cultural fault lines and pre-decided moralities, steered into politics before they are fully weaned. It is a first touch, one could say, with belonging; children urged to grapple with identity before Arabic has fully healed in their mouths.

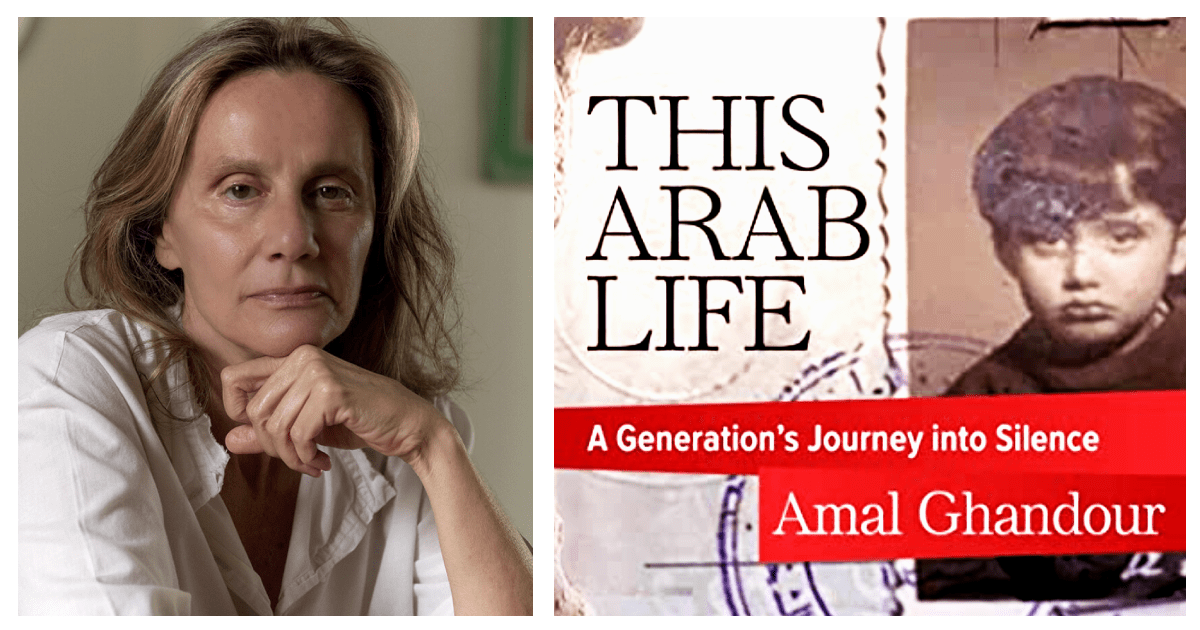

In ‘This Arab Life: A Generation’s Journey into Silence’ (2022), Amal Ghandour presents a solitary vision—sacred in its documentation of the past and its fragmentary exploration of the Arab self, informed by a past unseen and an experience unforgotten. This is a memento and a memoir, both; it is a recollection of Ghandour’s experiences as a young Arab in the folds of turmoil and silence, punctuated with whimsical remembrances of a Amman and Beirut that, to many, no longer exist.

Ghandour transports her reader into memory and history, expertly marrying the two to deliver an unblemished, if not raw, understanding of Arab life. Between her vignetted storytelling of the 1970s, and her witty delivery of modern-day disillusionment, Ghandour is able to unpack the complexities that define the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and her own generation’s fall into complacency.

‘This Arab Life’ is a narrative that follows Ghandour from her first steps into the world, well into her adulthood, with sentimental remittances paid to each piece of her tale. Its inductive approach allows the specificity of Ghandour’s experiences to unfold into larger, more poignant understandings of war, revolution, religion, and virtue.

As “Lebanese-born and Jordanian by circumstance,” Ghandour’s story begins when she is just five months old; her father, an activist by nature and revolutionary at heart, is sentenced to death by the Lebanese state in 1962. Accordingly, her family is forced to flee the political duress that shadows them out of Lebanon and into Jordan, where Ghandour spends most of her formative years. It was this move, perhaps, that served as both a cornerstone and trigger for her literature and her journey.

In more ways than one, ‘This Arab Life’ is an excavation of the self—but above all, it is a promise to its reader, delivering what it sought to deliver: grainless insight into the Arab condition. In Ghandour’s own words, this is “a testimony to the untethered self, even when still held by anchors, or in a straightjacket by lazy prejudice and stereotype.”

On Repackaging Politicism?

“It was February 2011. Arabs were beginning to rise like waves of surf. In the dead of winter, Spring, it seemed, had finally arrived,” Ghandour writes, deconstructing an instrumental turning point for the Arab world. This sets the tone for ‘This Arab Life’ as a political journal, one that is careful and articulate in its pulling apart of despotic seams and inherited disillusionment.

While some scholars lionise the Arab uprisings, and others denounce the Spring’s failures, ‘This Arab Life’ is a narrative built from the bottom up, in a crescendo that seeks to explain the hows and whys behind the region’s present day political landscape.

Despite teasing an understanding of the Arab Spring early in her book—in all its bedlam and euphoria, recourse and revelation—Ghandour does not start there. She instead directs the reader over historical landmines, such as Saddam Hussien in the Gulf and the Syrian Labour Communist Party’s questionable influence, how jaded pragmatism defines the present moment. Within her profound understanding of these political events, and her extrapolations, Ghandour breathes life into MENA’s political past; while the world remembers only the Arab Spring, Ghandour remembers a 1980s Amman, and the warning signs of Zionism.

In ‘This Arab Life,’ the Spring is just one facet—a modern one—of Arab history. What Ghandour does is skillfully navigate the histories of an entire region to better understand what the “Arab life” truly entails. From Nasserism and Wahhabism, to Liberalism and Communism, Ghandour takes bits and pieces and recenters them in context.

In conversation with Egyptian Streets, Ghandour expresses key insights into the link between the younger generations and her own.

“What the new generation is experiencing today is a much darker shade of what we were beginning to experience then,” she explains, “I felt compelled to write a book that made that connection.”

‘This Arab Life’ becomes a “prism” that prompts us to imagine the next five to ten years. Ghandour’s narrative transforms the past into a mechanism to anticipate the future.

“A common misconception the younger generation has, one especially evident in the Arab uprisings, is that mobilisation equals organisation,” Ghandour delineates, careful to make the distinction, “Mobilisation does not equal organisation. It’s organised politics that give you a chance of survival; it’s your labour unions, your trade unions, your independent political parties that can sustain and organise presence on the ground. These are what impose a price high enough for a regime to take you seriously—[the Arab Spring] did not.”

Moreover, Ghandour argues both in person and within ‘This Arab Life’, that her book was not written with the intent to redefine politics or change what has already come to be; it is, at its heart, a reflection.

There is no aim to justify or vilify, and there is no romance in Ghandour’s view of revolution—only facts and figures, lived experiences. ‘This Arab Life’ carries an impartiality unexpected from a book that so heavily relies on collective memory and personal exploits. Ghandour does not attempt to answer questions about the rights and wrongs of political systems, she only seeks to describe and understand their architecture through her own writing.

Still, embedded within that impartiality, Ghandour is able to unearth the harsh undercurrent of political spheres across MENA.

“[Arab] regimes don’t pretend that they want to care for us, and we don’t pretend to love them,” she confides. “Because who would believe them, and who would believe us?”

In her own words, there “is no social contract anymore between regimes and people,” not anymore. This disconnect, which first took form in the 1970s and expanded into an overhang of numbness, has manifested itself in the silence of generation after generation.

Much like the title of her book suggests, Ghandour concerns herself more with the silence that follows Arab politicism and the divorce of people from political systems. Although the book unpacks the trauma and passiveness of Ghandour’s generation—one that came of age in the 1970s and 1980s—her arguments present a timeless vision of the Arab political self: one that is meek, submissive under the weight of dictatorship.

“We have to show real respect for at least a few of the tropes, or explanations, that have grown automatic for us,” Ghandour tells Egyptian Streets. “Despotism motivates a certain kind of pragmatism. Let’s not underestimate the degree to which tyranny can numb the senses and inhibit action. If you do something, you’re really doing it on the pain of death—and justifiably, it’s a sacrifice a lot of people don’t want to make.”

Ghandour’s arguments take more than one shape, and it is not only traditional dictatorship she believes encourages silence. “We also have to respect New Liberalism, and its numbing tools that came into existence in the 1980s. It is the juggernaut that came to complete the job [of dismantling the structures of dissent].”

She extrapolates that, because of the sheer efficacies of tyranny, police states tend to be rigid and hard to unseat. Rather, “in such places where the state is absent,” argues Ghandour, “only one apparatus works: the security apparatus. It’s fickle. You are either in a deceptively free zone, or you’re in the twilight zone. It depends on whose toes you accidentally step on.”

With a rich and often holistic insight into the tragedies of Arab politicism, Ghandour showcases a breathtaking slew of knowledge and wisdom. She is able to present the suggestion of politics rather than a constricted definition of it; throughout the book, Ghandour is keen to distance herself from her generation’s disdain for politics; instead, she presents her knowledge as an invitation to better understand her generation’s political silence.

On Memories and Histories

The gripe of the unreliable narrator is an old, well-known one. Stories marred by opinion, skewed by memory—this is a worry which comes to a head here as well.

How are we to know whether Ghandour’s retellings speak to a universal experience? We are not to know for sure, and perhaps that is the point of ‘This Arab Life’; Ghandour does not attempt to make such grand claims. She presents her reader with a story—her own—which is as valid as any other Arab tale of diaspora in motion.

She tells Egyptian Streets of a conversation shared with her nephew, a man born at the tailend of Generation X, and the cusp of Y. He’d expressed his utter bafflement with her retellings of the Arab world; to him, these were not places that existed in his own memory. With “anguish and frustration”, he asks Ghandour to elaborate on the Beirut and Amman of her world, doing his best to reconcile them with his own to no avail.

That’s why, Ghandour argues, ‘This Arab Life’ is an important piece for the new generations to observe.

“When I hear that this book resonates with the younger generations, it tells me that I’ve at the very least succeeded in reweaving these connections, in remedying this severing of memory that finds so many of us ever so lonely.”

The Arab experience is not tethered to a single story, but it can be understood through one. From chequered understandings of war, revolution, and politics, ‘This Arab Life’ is an ode to the past and present both. Ghandour’s history punctuates her experiences, certainly, but the allure of ‘This Arab Life’ lives in its misty, well-chosen memories, in the moments where Ghandour finely details her days and the characters within them—where she nails down what it means to be an Arab in the modern and postmodern world.

Ghandour summarises it nicely in a single statement: “I am content to be identified as an Arab, impatient though I am with the trappings of identity.”

Comments (0)