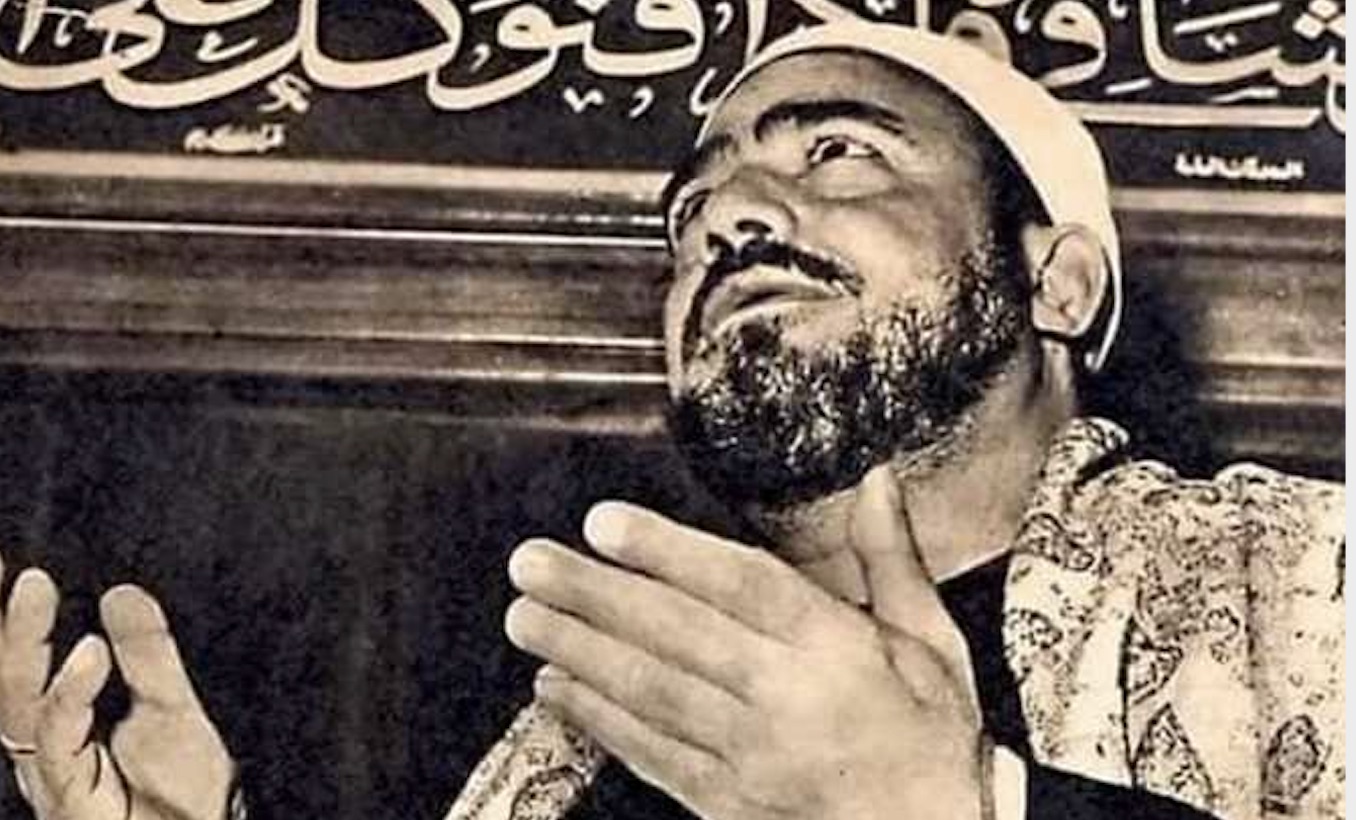

With a voice that transcends worlds and soulful techniques that touch the heart, Sheikh Sayed Al-Naqshabandi’s Sufi prayers and chants—where beauty laces each word—are a pillar in Egyptian spirituality.

Born in 1920 in the village of Demira, in the Dakahlia governorate, Al-Naqshabandi started learning the art of inshad dini (Islamic hymns) — Sufi poems recited alongside musical instruments — at the young age of eight.

Since the days of his youth, Al-Naqshabandi followed the techniques of chanters, but it was not until 1955 that the munshid (inshad performer) rose to fame. He performed both in Egypt, the region, and beyond, visiting Syria, the Emirates, Iran, Morocco, and Indonesia.

View this post on Instagram

In 1966, he met with the late radio broadcaster Ahmed Farag at Al-Hussein Mosque in Cairo, where he was introduced to the world of radio broadcasting.

After recording several episodes for Farag’s show Fi Rehab Allah (In the Company of God), he went on to record religious prayers for the daily show Doaa’ (Prayer), which was broadcast after the maghrib prayers. To many Egyptians, his voice has become synonymous with the holy month of Ramadan, where his famous prayers, introduced by his chant “Allah ya Allah” follows the call to the maghrib prayer, accompanying Egyptians as they break their fast.

Al-Naqshabandi also performed one of the world’s most famous Ibtihalat (spiritual poems that are recited by people to express their deep love, prayer to God), Mawlai (My Lord). Many of Al-Naqshabandi’s prayers and recitals were composed by music icons, such as Sayed Mikkawy, Baleegh Hamdy, Mahmoud al-Sherif, and Helmy Amin.

His famous religious singing, “Oh God, at your door I stand hoping for support and mercy,” remains embedded in the hearts of many Egyptians.

Mostafa Mahmoud, Egyptian doctor and philosopher, described Sheikh Al-Naqshabandi’s voice as a noble light that no man has ever reached. Vocal experts unanimously agreed that his voice was unmatched—as only few can, he could sing across eight octaves.

In 1976, Al-Naqshabandi died of a heart attack, but left behind a legacy of remembrance. One of the main streets in the city of Tanta, where he lived and was buried, was named after the late munshid.

47 years after his death, the sincerity of his voice and the spirituality he embodied remain an emblem of mysticism and faith.

Comments (3)

[…] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Egypt led the revival of these musical traditions with regional icons like Umm Kulthum, Abdel-Halim, and Shadya all performing Ibtihalat throughout their careers. The artforms were further mainstreamed through radio and later television broadcasts in the 1960s, with voices of legendary munshideen like Sheikh Sayed Al Naqshabandi’s coming to form pillars of Egyptian spiritual life. […]

[…] Source link […]