To some communities, writing is not only for reading — it is for being. It is breathing life into their existence, it is understanding what was in the past, and what will be in the future. It is uncovering layers of human archaeology: a house, a loose window, or a library. It is digging, harvesting and seeding emblems of history, heritage, and identity.

The vein of identity construction has always existed in the body of writing and storytelling. Storytelling customs exist in many cultures, serving various purposes, including education and faith. Yet for the Bohras — a Muslim community within the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam — one of the main purposes of writing is also to shape and preserve cultural memory, enabling communities to connect with their heritage. Who they are, who they will be, and why they are here are all questions that are answered through written manuscripts.

As I walked into Zara Hashmi’s home in Texas, a large portrait of Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin — the supreme leader of the Bohra Community — was hung on the wall. Hashmi is among the Bohras of Pakistan, who trace their heritage to Egypt’s Fatimid dynasty. Piles of archival books, photographs and documents were safely kept inside several drawers, and each one traced the story of their community from the beginning to contemporary times.

“This is when Syedna Burhanuddin visited Egypt to preserve Fatimid heritage,” she tells me as she points to an old photograph in a thick book. “He played a key role in the restoration of al-Jami’ al-Anwar, the masjid of the Fatimi Imam al-Hakim.”

When they are born, Bohra Muslims listen to stories of losing land, losing family members, and losing their homes due to religious discrimination, Hashmi tells me. Isma’ili Shias have been marginalized and discriminated against for decades, repeatedly displaced, and were largely excluded from political representation in their home countries, particularly India, Yemen, Pakistan and countries in East Africa. Not only were they deeply vulnerable to sectarian violence, but they also had to face violent campaigns that aimed to completely exclude Shias from public life, one of the recent ones being in Yemen in 2015 following an attack by ISIS.

However, these campaigns have deepened their unwavering commitment to their faith and identity, creating an exceptionally tight-knit community that is distinguished by its governance and authority, as the centrality of the top cleric or the supreme leader in their religion sets them apart from other Muslim groups. This kind of authority has allowed the Muslim Bohras to remain guided by their religious leader, who provides them with a sense of direction and supports them in situations of economic or social hardships.

“From morning to night, we are tied to the community,” Hasmi says. “We have our breakfast at the mosque early in the mornings, and then we gather in the evenings.”

To recall the past is a source of strength, and for the Bohras, the stories and artefacts they protect are tools in resisting the systems meant to exclude and erase their voice and identity.

The Khizanat in Fatimid Cairo: Tools of Resistance

One of these tools of resistance is through the khizanat al-kutub, or treasury of books. While identities today are usually defined by Western understandings of nation-states and modern territorial borders, Olly Akkerman, one of the few researchers on Arabic manuscripts and Shi’i Islam, underscores the role handwritten manuscripts play in preserving the cultural memory of the Bohra community.

In her monograph, A Neo-Fatimid Treasury of Books, Akkerman analyzes how ancient manuscripts can construct one’s identity and voice as a part of the Bohra community, and how it creates new meanings in new social realities.

These manuscripts play a significant role in the self-understanding of the Bohra community, so much so that even though they live across the Western Indian Ocean and have a strong presence across Europe and North America, they are still strongly connected to their heritage in Egypt, where the Fatimid dynasty was centered.

As Akkerman poignantly reflects, “one would almost forget that the community has a rich history in the Indian subcontinent for over five centuries,” due to the community’s fervent relationship with Fatimid Cairo.

The Ismaili Fatimids ruled much of North Africa and the Mediterranean region in the 11th and 12th centuries, making Egypt the center of the empire. They were widely known for having one of the largest libraries of their time, also known as the House of Wisdom.

The word “Bohra” is derived from the Gujarati (an Indo-Aryan language) verb vohrvun, which means “to trade,” reflecting the vast majority of Bohras’ historical occupation in India. During the Fatimid era, the Indian community in the state of Gujarat — the western coast of India — traveled and maintained ties with Fatimid leaders in Yemen, who regularly welcomed the Bohra community, of which many converted to Islam as it grew in size.

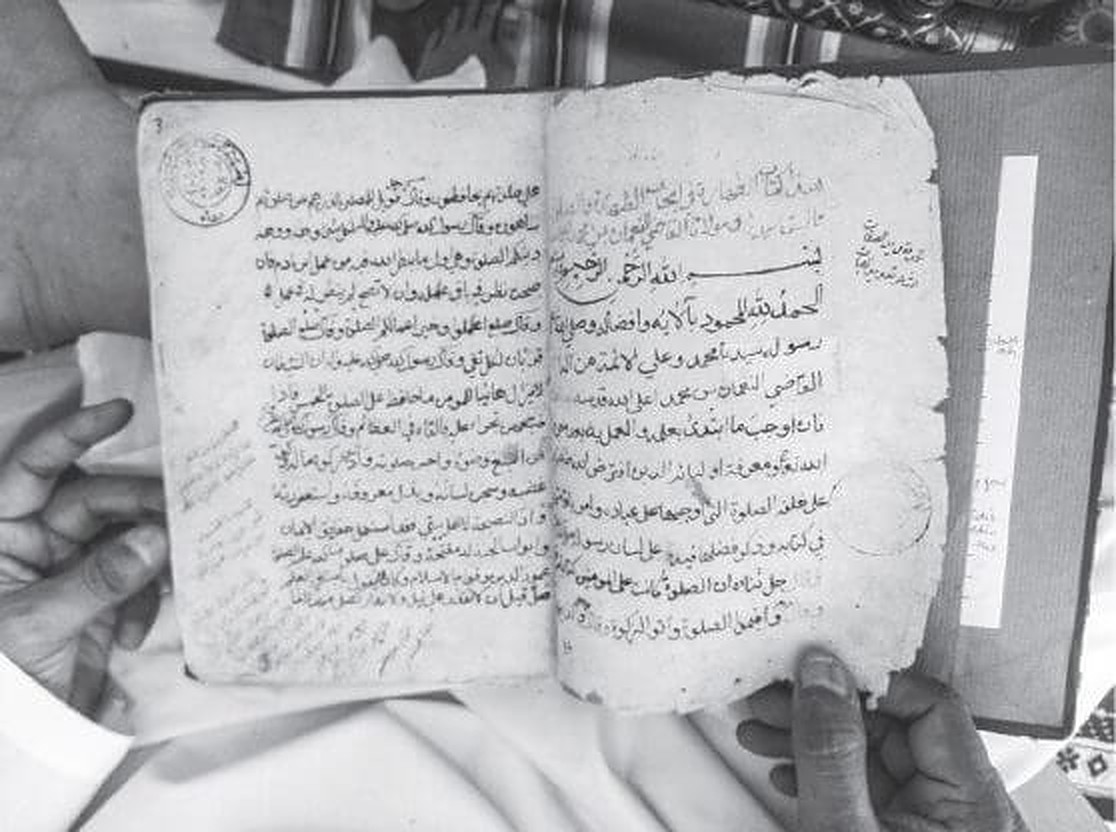

A majority of scholarship argues that after the Fatimid empire was overthrown in the twelfth century, the treasury of manuscripts disappeared forever. Yet recent research has shown that Fatimid books continued to be circulated for centuries after the empire’s fall, a process that is documented in several post-Fatimid historical works.

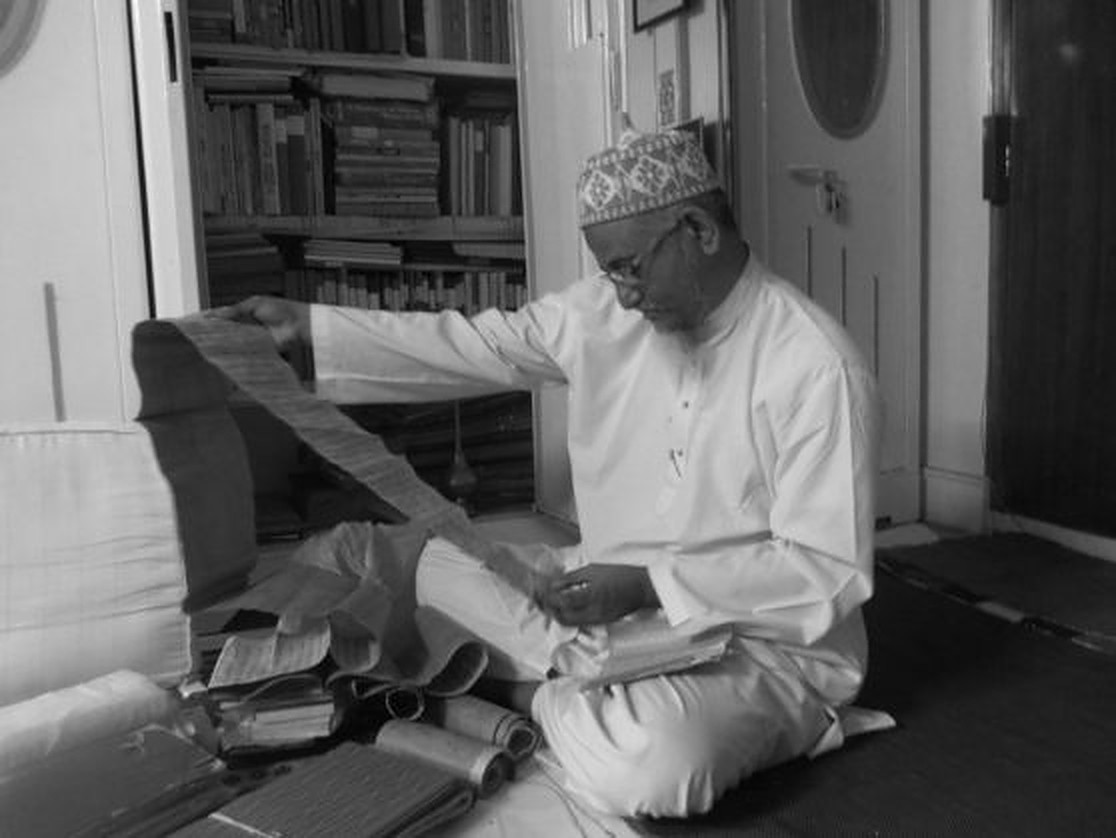

Fatimid manuscript tradition and rich intellectual history continued to be read and copied by the Isma’ilis in Yemen and the Bohras in India. Based on her fieldwork, Akkerman observed how ritualised transmission practises of copying manuscripts allows modern Bohra clerics to trace and connect their tradition with historic Isma’ili book treasuries of Fatimid Cairo.

The Bohra community’s identity is ultimately fortified by their ability to preserve, copy, collect, enshrine, and venerate these ancient manuscripts, which also validates their status as the Fatimids’ heirs within the larger Shi’i community. The cultural memory of their Muslim identity is not just preserved through religious practices, but also through handwritten manuscripts.

These manuscripts, also known as sijillat, traveled from India in the form of diplomatic rolls written by the Indian Dais (someone who engages in inviting people to Islam) to their representatives in the Fatimid dynasty up until the nineteenth century and later. The fact that these manuscripts are official royal decrees issued and signed by the Indian Dais in their capacity as the leaders of the Bohra community is what plays a central role in affirming the identity of the Bohra community today.

It is important to note that the content of these manuscripts can only be revealed to certain audiences within the community, and due to their secrecy and sacredness, no studies have been published about them.

Lost Worlds, New Identities

The influence of these handwritten manuscripts on the Bohra community are a manifestation that identities can grow beyond territorial borders, and that although Egypt is predominantly defined by modern ideas of citizenship, there should be room for other communities to belong and reconnect with their heritage.

The restoration of the Mosque of al-Hakim, also known as Al-Anwar, in 1980 signalled the beginning of a revival of the hidden connection between Bohra community and Egypt, and the growing interest of the community to travel to Egypt and rediscover their identity and cultural memory.

Over the years, the Bohra community have carried out various efforts to preserve Fatimid Cairo. In 2022, Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin — present leader of the worldwide Dawoodi Bohra community — joined President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi for the opening of the al-Husain Mosque and the shrine of al-Imam al-Husain, which had undergone major renovations. The holy sepulchre was repaired by Saifuddin, who also decorated it with gold and silver.

Shortly before he passed away in 1965, Syedna Taher Saifuddin installed the first sepulchre. His successor, Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin, inaugurated it later, who had been summoned to Cairo by Deputy Prime Minister Ahmed al-Sharbasi in 1966.

In 2021, Al-Sisi also extended his gratitude for the charitable activities done by the Bohra community in Egypt, in addition to Saifuddin’s support for the “Tahya Misr” fund.

This year, Hashmi tells me that she will be visiting Egypt for the very first time with her family.

“I am so excited to explore Fatimid Cairo, we’ve always wanted to pay a visit but never did,” she tells me.

Though she and I come from completely different countries and different cultures, our history is intertwined through a lost world that continues to be kept, preserved and collected by the Bohras.

“Except for the Bohras, this was never a world lost to begin with,” Akkerman writes.

Comment (1)

[…] post Protecting Lost Worlds: The Bohra Community’s Relationship with Egypt first appeared on Egyptian […]