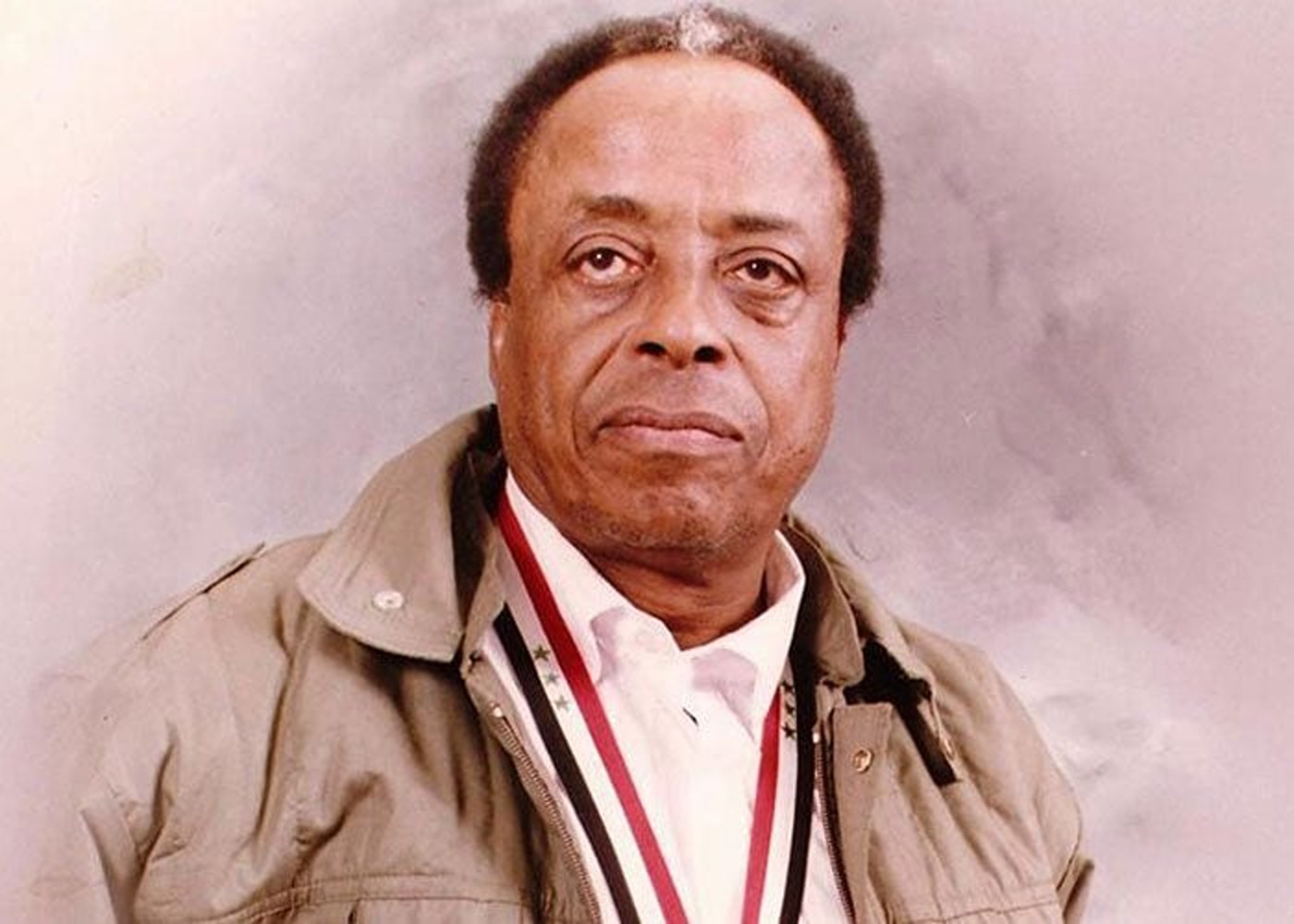

“I shall lie like water on the Nile’s body,” writes Sudanese-Libyan poet Mohammed el-Fayturi in his beguiling poem Dig No Grave for Me. “Like the sun over my homeland’s fields.” Nurtured by the sun and water, el-Fayturi envisions Sudan as a living being nourished by nature’s grace; a homeland that breathes through its rivers and fields. He places himself, and those who resist oppression and colonialism, in the position of nature itself: to serve, to protect, to give life, and never to steal or betray. Like the sun, the fighters against tyranny rise each morning. They do not fail to return, they do not abandon the earth in darkness. And like the Nile’s waters, they continue to flow and run, remaining loyal, faithful, and alive. For el-Fayturi, the fighter does not die, nor do they vanish into a grave as the oppressor might wish. In his verses, the oppressed endure and their cause ascends with every sunrise, refusing to be buried. In our world today, where the oppressed are slaughtered in staggering numbers and where triumph is too often measured by violence and war, el-Fayturi’s words echo across time,…

My Heart Is Devoted to You, My Homeland: Sudanese Poets Sing of Love and Loss

October 7, 2025