First came the age of cable and satellite television. The predictable structure of daily and weekly newspapers and terrestrial networks was lost. The game changed.

Then the internet’s arrival was next. The players increased exponentially. Access to information widened drastically. The game changed again.

And then, social media emerged. Anyone with an internet connection was suddenly able to say anything about absolutely any topic at all. The game didn’t just change. The rules were eliminated altogether.

Today, information dissemination and consumption have become a positive minefield for everyone from journalists to citizens trying to keep track of the ever-unfolding events worldwide.

The ethical and professional standards that are applicable in media organizations no longer have any power over the information ecosystem, and social media platforms are riddled with false news, both intentional and unintentional.

Political polarization is rife in almost every country in the world and this polarization is evident in nearly all information sources, whether those be established media organizations or personal accounts giving their two cents on whatever’s going on. There is an information overload, and no practical way to regulate it.

In my time both as an undergraduate and as a postgraduate, I spent a lot of time studying the different responses to this chaos; my thesis was on the ways in which journalism can evolve in this fraught media landscape.

Through my research, I have concluded that the persistence of factual journalists to report true and meaningful stories is essential in debunking falsehoods polluting the media environment, I also concluded that there is a need to get with the times and find more accessible ways to inform audiences.

And what I found is that for most of history, there has indeed been a more accessible, and in fact more entertaining way to expose unreliable information, political uncertainty, and social injustice: comedy.

The concept of a “fool” or “jester” is nearly as old as civilization itself, with mention of such characters in Ancient Egypt and historical China. A storied figure, the jester’s most iconic form is from medieval courts, where colourfully dressed professional jokers, whose mission was to mock powerful politicians, enjoying an almost inexplicable freedom of expression, when no one else did.

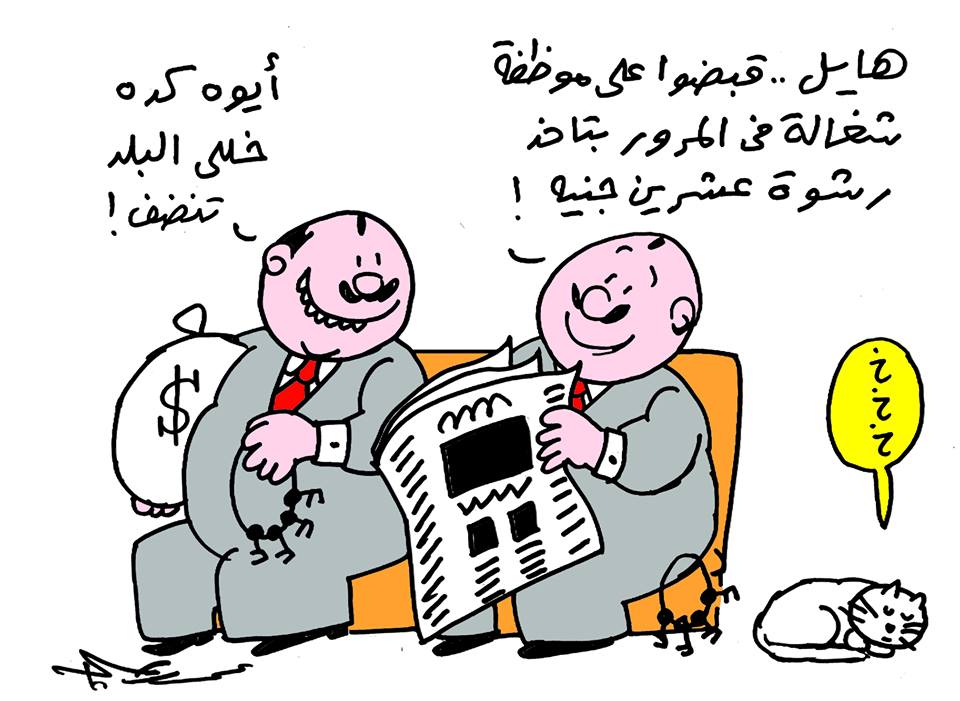

Long after the jester, political satire has now evolved with the times, and around the world, different forms of humorous responses to political events emerged, such as cartoons in newspapers, and stand-up comedy, and more.

But a gap formed when many established media organizations became guided by their corporate or political interests, and their complacency allowed satirists to joke their way to positions of intellectual and political power, much like jesters once did.

Over two decades ago, Jon Stewart embarked on his journey as host of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show (now hosted by Trevor Noah). This show was a phenomenon, and is considered to be responsible for the burgeoning of a format of political satire that was named ‘fake news’ before the term gained its new meaning in the past few years.

Over his time as host, Stewart guided to success numerous comedians who have now themselves become household names in the world of political satire. John Oliver, Stephen Colbert, Trevor Noah, Samantha Bee, Hasan Minhaj, and many more have made ripples in the media landscape with their humorous handling of a wide variety of social and political happenings.

While they all insist on the fact that their parodic news-like format is merely part of the joke and that they are by no means journalists, surveys and studies have shown that many people rely on their programs for news more than they do on traditional news networks. In fact, some studies showed that, in Stewart and Colbert’s heyday, their viewers were more accurately informed on current events than the viewers of mainstream news shows in the United States.

The strength of this type of format is undoubtedly its ease of consumption and clear objective to entertain. This was clearly visible at home, when during the years following the 2011 revolution in Egypt, Bassem Youssef – who was incidentally also inspired by Stewart – broke TV records with his satire show Al Bernameg.

While it is known that the way to the hearts of many is laughter, it is important for us to note that it is also the way to the minds of many. Those spreading false information are unshackled by the facts and standards respected by real news, so those who prioritize truth are in a position where they must be more creative in how to effectively inform their audiences, and equip them with the toolkit to identify falsehoods.

In Stewart’s famous monologue in his final episode as host of The Daily Show in August of 2015, he spoke of the different types of institutionalized deceit, as he phrased it, that permeate society. Describing them in comical yet extremely censorious detail, he left his final legacy to all those who watched the show:

“Now the good news is this: bull****ters have gotten pretty lazy and their work is easily detected, and looking for it is kind of a pleasant way to pass the time. Like an ‘I Spy’ of bull***t. So I say to you tonight, friends: The best defense against bull***t is vigilance. So if you smell something, say something.”

Comments (0)