By Tanya El Kashef, Community Times

It was not too long ago that Tahrir Square echoed with chants demanding social equality and opportunity. When President Hosni Mubarak announced his resignation in February 2011, roars of excitement emanated from all corners of the square; drumbeats and happiness laced the air, and for a moment, it seemed like everything was going to be okay.

While to many people these images have become somewhat mundane, eliciting what are now dull feelings, there is one chant in particular that, due to its simplicity, continues to resonate long after the crowds have dispersed. As herds of young men and women gathered that night, jumping up and down with joy beneath the sparkling fireworks, one group of young men had only one thing to say: ‘We’re going to get married.’

Though such a direct statement about marriage may seem out of place within the political arena, it is very telling of the larger picture and the genuineness of the masses’ demands. In order to get married in Egypt, one must have economic stability; therefore, having a secure income is equated with the ability to gain autonomy – in other words, get married.

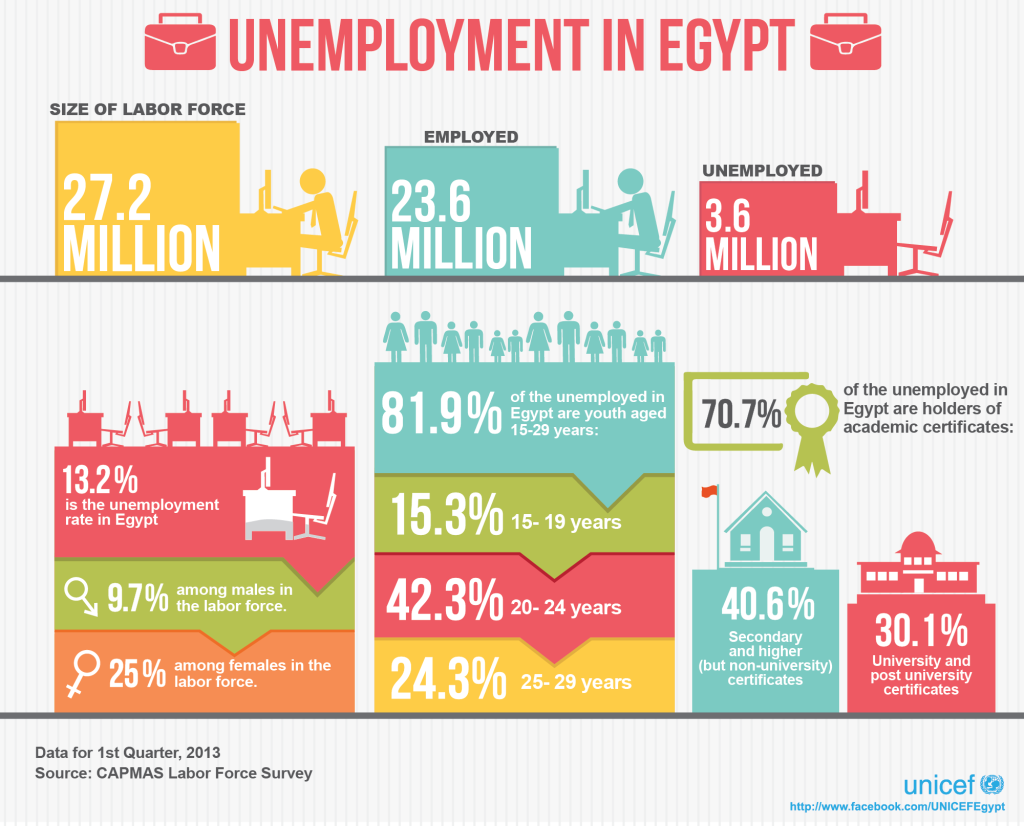

However, according to research carried out by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) in 2013, unemployment rates in Egypt reached over thirteen percent, and of those unemployed, over eighty percent were high school graduates and college degree holders. With a job force increase of about four percent every year – in a country where a quarter of the population is under the age of 25 – it turns out that high school and college graduates are just as likely to be unemployed as those who have not completed elementary school. So to reiterate the question, why can’t the average, educated Egyptian find a suitable job?

An Eye on Education

While Egypt’s largely young demographic plays a significant role in the high unemployment rates, there are certainly other factors at play. The inefficiency of the public education system could be regarded as the primary cause of the shortcomings of the labor force; apart from the lack of skills’ training at these educational institutions, and the limitations this creates for real life work opportunities, it is important to note that among the jobs that become available to those who are qualified, few of the positions truly fulfil the needs of a young person looking to become independent. In fact, the job hunt itself is further entangled with social expectations and stigmas, which are a critical hindering factor in professional opportunities.

Although many nations face unemployment problems, Egypt is unique in the over-centralization in Cairo – an ingredient that has only added to the existing problem. While the Egyptian capital is oozing at the seams, limited in its classrooms and industry, offering less physical space and fewer opportunities to the masses, other parts of the country remain sparse and starved of healthy development despite their wealth in resources, thus perpetuating a toxic cycle.

To trace the problem back to the source, the path inevitably leads to the standard of public education. While education is free and available to everyone from elementary school through to university in Egypt, its actual functionality is largely skewed. School systems and curricula continue to be out-dated and weak, and classrooms across all levels of learning, particularly in Cairo, are hideously over-crowded, making learning near-impossible and failure almost imminent. This year, over 90 percent of Cairo’s high school students passed their secondary exams and went on to universities; however, with so many students and so few universities, one must ask: where will they all go?

As part of the flailing workforce themselves, teachers are usually over-worked and underpaid, and thus perform weakly in the classroom and look to private lessons for extra income. Since students are not immersed in a conducive learning process, they too turn to private lessons to make up for the lack of education in the classroom, and so the cycle goes on. The reality of schools and education are the perfect microcosm of the issue at large.

Institutes of technology and vocational training are also readily available and offer instruction in a wide range of fields, including business administration, tourism and hospitality, sales and marketing, and television. However, these institutions are ultimately bootless, since they lack competence and proficient education. Those who study communications, for example, end up with little knowledge of computers and software usage, and in turn fail to meet the most basic job requirements.

According to Tarek, 58, an executive producer at a media company who has managed employees for over twenty years: “The unfortunate part is that many communications’ graduates come to us without the most basic knowledge of computer software, and when it comes to working in this field, that’s obviously a big problem.”

The deficiency in effective education is only one side of the problem though – albeit a detrimental and infiltrating one. On the other end of the spectrum, those who have managed to get an education and acquire the necessary skills to carry out a certain job are often faced with one of two problems: either the jobs on offer provide less security than is needed in real life, or there are no jobs available to them to begin with.

White-collar, blue collar

The truth is, a suggestively high number of working class jobs are filled with college graduates and other diploma holders. Speaking to a range of degree and diploma holders who work in blue collar jobs, it would seem that while satisfying, white collar jobs are scant in themselves; many point out that the positions available can be temporary and project-based, or pay too humble a salary due to the difficulties that companies themselves face.

This is where the effects of the revolution should be taken into account. Since the backlash of the January revolution resulted in many companies going bankrupt and closing, especially tourism affiliated ones – not to mention dwindling international investment – positions have become few and far between.

With a diploma in communications, Ahmed, 25, drives a taxi, but once held a stable and promising job as an operations manager at a limousine company in Giza. Ironically enough, after the revolution that symbolized so much hope, the company began to face problems and he was forced to find a different source of income. Ahmed eventually resorted to driving a taxi since his other options were both temporary and project based, or demanded exceedingly long working hours at meagre pay. In the end, he found that driving a taxi was more auspicious, explaining that it “produced direct results and ultimately paid better.”

However, he also concedes that he still cannot afford to become independent and get married. Other than the repercussions of the revolution, jobs more often than not fail to provide the necessary means to support family life.

Ibrahim, 45, has held a government job in the Ministry of Industry for the past twenty-eight years and still receives a minimum wage salary unfit to support a family, so in the evenings, he takes to driving a taxi as well; with a chuckle he says, “What else was I supposed to do? Steal?”

Social structures and stigmas seem to play a leading role in weakening Egypt’s work force. Work environments continually favor those already at the top and stifle those trying to rise by remaining old-fashioned and mostly hierarchal. These rigid systems and authoritarian models remain the norm within the Egyptian work force, where, more often than not, managers and business owners fall short of motivating their employees and leading by example. These two ingredients, which remain key to healthy work environments regardless of the level of education of the workforce, often stifle the growth of healthy competition and diminish the invariably positive impact of concepts like team work and employee empowerment. Moreover, there is an evident discrepancy between the type of education that is socially accepted, advocated, and offered, and the reality of society’s expectations and its mechanisms.

Egyptians are flagrantly pressured to choose a ‘respectable’ field for their studies – one that preferably adds a title to their name despite the lack of sustainable prospects, since it is more socially prestigious to be an engineer or a doctor than an electrician, even though that same electrician may eventually become a business owner by taking pride in their job. However, the government and Egyptians at large support white-collar education, and technically provide it, but fail to meet the resulting demand for suitable jobs.

Thirty-year old Khalil is a law graduate, but instead of working at a law firm or a company, he works at a restaurant; Amr, 25, studied computer science for four years at a technical institute but works at a gym.

Mona, 26, has a diploma in accounting but struggles to find any job at all, while Mahmoud, 26, also holds a diploma and is equally unlucky. The current issue of unemployment – or more accurately, the issue of underemployment – seems to correlate with the ideals placed on family ties and social background. The manner in which the working class is regarded continues to have an effect on the evolution of the labor force as a whole.

Take forty-seven year old Saleh as an example. The son of a doorman, he holds a bachelor’s degree in science with a specialization in math; however, for the past twenty years he has worked unofficially for a family, managing their real estate property in the suburb of Maadi in Cairo, simply because he has found no other viable work. While his position could be considered favorable due to its stable income and agreeable work conditions, the fact of the matter is, Saleh’s job is officially unrecognized, which means that he has no insurance and no chance of eventually receiving a pension. It would also be to his personal benefit if he had a job that matched his intellectual capabilities.

Social nuances continue to rise as one moves down the family line; Saleh’s eldest son recently completed secondary school and chose to enlist in the army, but as the son of a doorman himself, Saleh expressed concerns with the background check portion of the armed forces’ entrance exam. He bears witness to the fact that one’s background matters and will likely impact his future, regardless of his actual capabilities and potential. The potency of these stark social dynamics is apparent from the moment an individual begins their education and continues into the professional realm, perpetuating a whole other destructive cycle. Of course there are exceptions; there are those few individuals that surpass these social constrictions and unleash their potential, however, the vast majority rarely do.

Cairo-Centric

Another decisive factor in Egypt’s employment conundrum is its centralized development, which is focused on the capital and governorates like Alexandria and the Red Sea.

Essam, 41, is from Aswan and holds a diploma in commerce; he lives in Cairo and works as a private driver. He says he never intended to leave Aswan, where he lived alongside his family in a house that overlooked the Nile. However, according to him, job opportunities there are not only scarce – they are practically non-existent, and the absence of industry and inactive market left him with no choice but to move to the capital.

Cairo is the refuge for many people like Essam from governorates all over the country, but the capital is far too populated and starved of prospects to absorb them all. With too many college students graduating from a select number of fields – including engineering, medicine, law, and commerce – seeking jobs in limited industries, decentralization and physical expansion could prove imperative to easing the problems faced by Egypt’s labor force.

A quick look at standards of living around the world reveals that nations that score higher on the gross domestic product per capita (GDP) at nominal value tend to be smaller in size; these include Monaco, Qatar, Liechtenstein and Luxembourg. Based on these statistics, it would seem that the fewer people there are per square meter, the more room there is for individual growth, and the richer the nation is as a whole.

If industry and commercial development were introduced across Egypt, sectioning it into smaller, self-sufficient entities, perhaps the extraordinary demand on classroom space and disproportionate competition for decent jobs in limited industries within Cairo would decrease. By branching out and expanding, the nation can only benefit from strengthening its less central communities.

Comments (13)

Egyptian educated graduates simply cannot compete with the outside world. Their entire school life has been spent learning rote style with zero imagination or thinking out of the box. You cannot develop a country by thinking that reciting the Quran perfectly in tune is the way to do it.

Exactly. I’m a foreigner living in Egypt at the moment establishing a Home Care company in which we will be able to employ quite some people. When people want to work for me they ask me first what the salary will be. Well, I first would like to know why I should hire you and what you could mean for the company. People have no clue how to apply for a job. And working for a foreign company means that we ask for proactive employees, hard working who will use the time they are in the office to do the work that needs to be done.If you want to play with your telephone then please go home and play there. Discipline in the work is really needed I think.

How did your home health care business go? I manage a home health agency in Houston, Texas and have some interest in opportunities in Egypt.

[…] Egyptian Streets […]