There are few realities I tend to hold, adamantly and harshly, against Egypt, and that is, for all its capacity to retain structures and mummies, for thousands of years, it is incapable of retaining our loved ones near us today.

To the most privileged, Egypt is a wondrous home where the idea of taking lagoon dips under the moonlight in Dahab, or sipping strong cocktails from rooftop bars, is not an impossible dream but a feasible reality. But, for others, the vast majority of its minorities, Egypt is a bitter and ungenerous space, ready to shun its most diverse sons and daughters.

For years, I lamented the dwindling voices of its minorities – atheists, intellectuals, LGBTQI+ members – forced to eclipse under the shadow of a majority. Most of all, I mourned, and still mourn, the fact that my generation will be the last to see and experience the few remaining Egyptian Jews in Egypt. In fact, Egypt is saying goodbye to the last handful.

They were 8 years old when they were expelled from Egypt. They were 14 and 10 years old. They were 20 and 12. The year was 1956; the difference between their inclusion and exclusion was stark. Only one day prior, they had shared school benches with Muslims and Copt classmates, but the next, they were being stoned for being ‘zionists’.

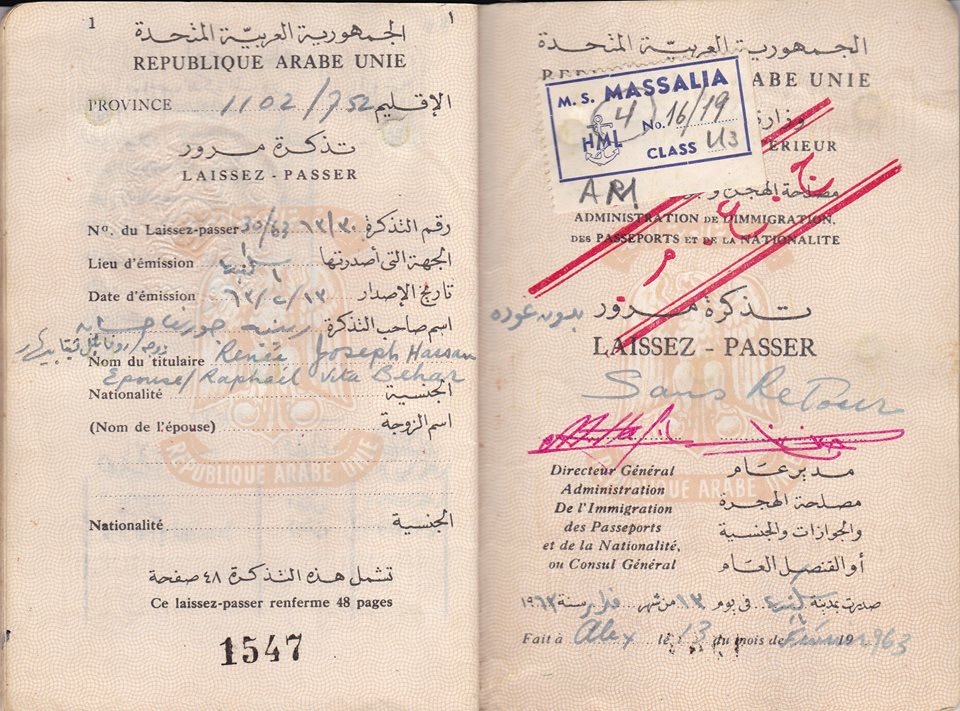

Then, the letter came. “Expelled,” was the judgment call. They had ten days to leave. And leave many did: between 25,000 and 30,000 jews, as well as British and French nationals who found themselves evicted for the role France, Israel and the United Kingdom played against Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez canal.

As such, when a generous spirit called Viviane Bowell, pitched her book “To Egypt With Love: Memories of a Bygone World” for me to read and review, I jumped at the opportunity of being familiarized so intimately with the former life of a Jew in Egypt, and chat with her.

Leaving behind a cultural ‘legacy’

Bowell’s autobiography was not intended as one. Indeed, what was meant to be a recipe book passed down to her grandchild, became a journey down in memory lane, with recollections of her journey to the UK.

“I wanted to talk about the Jewish community in Egypt: what we were like, what we ate, what we thought, our superstitions. You know, we’re quite unique, and I want that to probably be documented,” explains Bowell who adds a second reason for writing her book.

“I wanted to talk about Egypt itself because I noticed that, with a lot of people, they know nothing about Egypt, and they have a lot of misconceptions. Even supposedly educated people are very surprised when I say that we lived in apartment blocks or that there were trams in Egypt in the 1950s,” she adds.

In her simple but lovely memoir, Bowell starts with introducing us to her family origins, and the origins of many Egyptian Jews, a blend of Sephardic and Mizarahi. This book is an excellent introduction to anyone who wants to glimpse at a time Egypt’s communities were coexisting and thriving, as well as understanding the Egyptian Jewish genealogy.

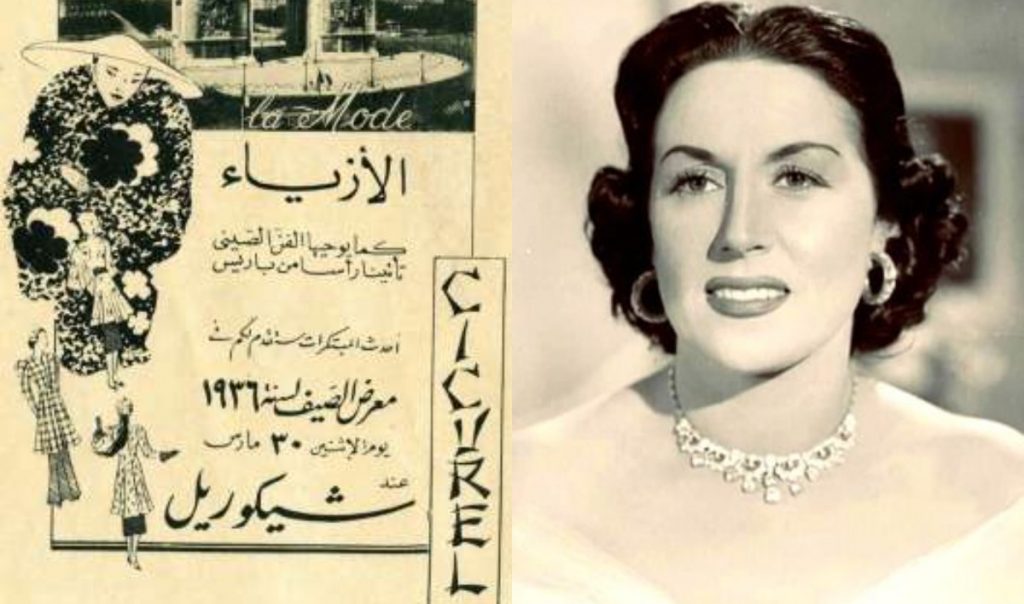

She addresses not just the Jews that formed her family, but also the Jewishness of Cairo’s social fabric for the first time; a reader can capture the nuances of the social classes, from the poorest who ate fuul as anyone else, to the “haute juiverie,’’ replete with financiers, bankers and socialites close to the royal family. The fashion industries and businesses which hailed from the Jewish community, such as Benzion, Grands Magasine Hannaux, Maison Circurel and Oreco. It almost comes as a shock to discover the ‘jewish’ origin of many ‘Egyptian’ big names: Smouha district in Alexandria is named after Joseph Smouha, a British Jew, the Frenkel brothers were behind the Egyptian equivalent of Mickey Mouse ‘Mish Mish Effendi’, and a throng of names, from Laila Mourad (born L,iliane Morchedai!) to Dawood Hosni and Togo Mizrahi were amongst the many contributors to Egyptian culture.

Generally, there are usually various elements that are lacking in books that tackle Jewish culture in Egypt, namely the cuisine and the celebrations of religious festivals, which richly stand out in ‘From Egypt to love’. With a love for cuisine that seeps out from the pages, the reader is invited to explore Judeo Egyptian cooking, largely inspired by Tunisian, Spanish, Moroccan, among others. She paints a fascinating picture of dishes, from hamud (vegetables in lemony sauce with potatoes and carrots) to sofrito (braised meat with spices and lemon), reminding the reader once more that Jewishness in Egypt was as varied as it was rich.

“Most of it [the book] was quite personal, but what I wanted very much was leaving a legacy: that, if somebody picks up the book, they think ‘Oh, this is what they [the Jews] did at Passover,’” explains Bowell, whose hopes for her project veered between preserving her family’s history as well as sociologically documenting the life of her community.

Bowell speaks of blending in the cultural, personal and historical background, as a tripartite mélange that can only give sense to her own life and mish-mash of cultural influences.

A flair for memories, a flair for style

Bowell is a phenomenal writer. Her style is no-nonsense, but it is still poetic. It feels like sitting with an old friend who has a charming, but meaningful story to tell. She is, above all, an honest writer, in the candid manner in which she captures simplicity and complexity, never amplifying either.

Prior to her family’s exit from Egypt, she writes “We had eyed the servants [house staff] nervously, wondering whether they would turn on us. They and all the local people around us remained very courteous and loyal to the end. They seemed sympathetic to our plight and were upset that we were leaving. On the morning of our departure, they all lined up to say goodbye.”

In other instances, Bowell can elicit a chuckle, as she learns how to navigate her new life in the UK, or she induces nostalgia, as she reminisces over old Egyptians expressions, games, meals, and rituals.

Alternatively, the brave writer’s explicit exploration of the prejudices, classist and old-fashioned streams of thought can also be shocking. She reveals how societal expectations can be oppressive towards all, namely women, no matter their religion or country of origin; she highlights that women often had to settle down, get married and devote themselves to the household.

True to its multifaceted purpose, the book is also constantly heart-aching, and never fails to highlight the second tragedy of the Exodus from Egypt: familial separation. Distant relatives ended up moving to various locations: kibbutz in Israel, London, Paris, and the US. It thus captures the unfurling of the Jewish diaspora before our very own eyes.

“ I used to see my aunts every day. Literally. I used to go. I used to see my mother’s sister every day,” narrates Bowell who also stresses that the lack of phones aided social interactions and community bonds.

“A lot of our friends ended up in Brazil and we never saw them again.”

More interestingly is Bowell’s take on the Exodus of the Jews in the 1950s. While she believes that the Suez Canal crisis precipitated the Jews’ exit from the country, the critical writer holds on to the belief that they were “collateral damage” in the political crisis.

“You see, it wasn’t just the Jews. It was Europeans too. It was the British who were not Jewish, French and everyone. It was just hordes of people whose lives changed because Britain and France couldn’t bear the thought that the Suez Canal was not theirs to run anymore,” she says.

When asked about the choice of the country, for the expelled Jews, Bowell explains that many opted for different options, including re-settling in Canada, Australia and the US.

“I think those who had a British or French or Italian passport opted for Britain, France and Italy, not Israel. Israel would have been the last resort,” she explains.

“A lot of people who were stateless and had no option would have opted for Israel. But, interestingly, a lot of them opted for Brazil because Brazil was welcoming a lot of stateless people.”

Her answers and her book provide answers to questions many have but feel unable to get to the bottom of. Even today, as a 2012 documentary ‘Jews of Egypt’ reveals, thousands of Jews who had lived in Egypt, live on, in mainland Europe, the UK, and Canada amongst many countries.

My own family, despite the multiculturalism my parents lived through in Alexandria and Cairo, does not speak of the Jewish legacy, as if the Jews never existed among Egyptians. When I visit Heliopolis, taking in the curious sight of the Vitali Madjar synagogue, I cannot help but imagine throes of men and women happily entering the temple before socializing in nearby parks or over a cup of Turkish coffee and maa’moul biscuits.

I am often haunted by their disappearance. The hand rails that are no longer touched, the menorah inside, no longer polished. I wonder to myself: where are they now? Where have they gone? What is their story? That is the story Bowell is aiming to deliver – a personal story which transcends the subjective: it is a story of one Jewish woman which is also a story of all the modern Jews of Egypt.

The personal: a tale of self actualization and forgiveness

The book’s story telling is straightforward, with a strong focus on the documentation aspect that Bowell initially started with. Yet, little by little, Bowell revisits each aspect of her past as well as relationship with her family.

In the midst of capturing the exodus that she, and many like her went through, Bowell also manages to openly reflect on the cracks of her upbringing, namely her parent’s difficult marriage. She humbly admits that her parents’ upbringing of her was faulty, yet she does not deny them the humanity of their error.

Moreover, she embodies the “getting on with it,’’ stiff-upper-lip attitude that many British people are known for. By leaving Egypt, and unlike the ‘Man in the Sharkskin Suit’ (by Lugnette Lagnado), her father’s reaction to having been evicted from Egypt is not ‘take me back to Egypt!’ but ‘forget about it.’

It is a stone cold reaction, yet one that is understandable and remarkable all the same. In writing her book, Bowell “makes peace” with her parents: a mother who instilled fear, and a father who was too controlling, despite their efforts to be supportive, providing and loving. There is a recognition of the sacrifices that have been made, as well as the resilience in needing to uproot from a life they cherished to be thrown into a different, unfamiliar country, whose even its winters they could not imagine.

The most poignant excerpt in the book, which affected me to the point of tears, was in reading the story of her younger sister Claudine, who died, after a long battle with terminal cancer. Bowell had not felt capable of seeing her in her last days. She writes “She died alone and this will always haunt me, as I should have been there to hold her hand; she may have lost consciousness by then, but I think at some level she would have known I was sitting next to her. A very kind nurse was with her until the end, but that does not exonerate me.”

For me, it was this particular passage that transcended religion and politics: tales of familial bond and resilience are all too familiar – they are irreligious and timeless. They live in a space in which they can be heard by any and all, and still inspire the rawest of emotions.

There is more to explore in the book, such as her attempts to explore and reconnect with the Egypt that she had once known, and even venture into her familial home, now occupied. Yet, it would be harsh to rob any reader the chance to learn more for themselves.

This may be Bowell’s own story, but, in a sense, this is also the story of thousands of Jews who had lived in Egypt. They might not be dwelling amongst us anymore, but their stories still do.

The book is available on Amazon (UK and international).

Main image: Ben Ezra Synagogue by khowaga1.

Comments (0)