Isolated and idyllic, the Siwa Oasis sits spun with sand and stone. Its water is clear, near-mythic, its shores baked with salt. For some, it is an escape—a place far removed from the bustle of the city. As the pulse of Egypt’s Western Desert, the location is a thing of immense beauty, sitting just short of the Libyan border.

For others, the oasis is much more than beautiful.

It is home.

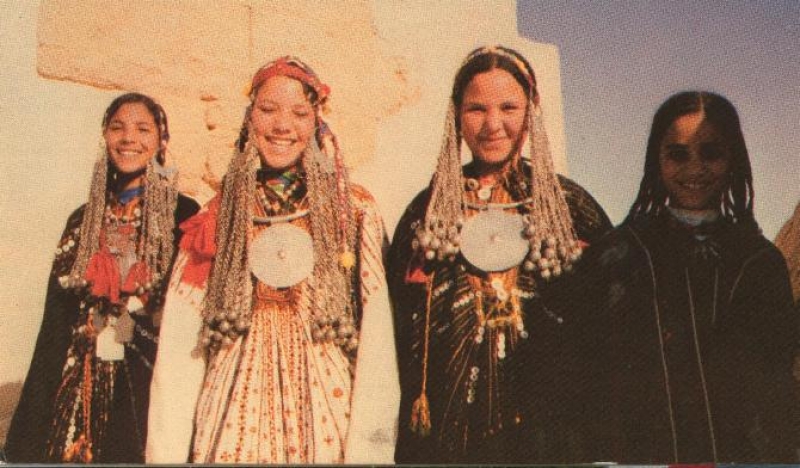

Among the palm and olive groves live the Siwi, a people of Berber origin often characterized as “independent, private, and resistant to central authority.” In their own words, they are Imazighen: ‘noble and free men.’ Nomadic in nature, the Siwi are farmers and vagabonds indigenous to North Africa. Although their communities are various, and often speckled with respective idiosyncrasies, the Siwi are most famously Swians: peoples who inhabit the Siwa oasis.

Their staple crop includes olives and dates, a romantic duo associated with their intrigue. To a lesser extent, the Siwi farm wheat, barley, sorghum, onions, and broad beans. Land is bought and sold amongst them, as are water rights; the Western Desert is arid and inhospitable, and their dependence on the oasis is essential to their survival.

As Berbers, they are the furthest East in comparison to similar Imazighen communities in Algeria and Morocco. Still, the Siwi adopt a Berber dialect (Siwah) that separates them from Arabic-speaking tribes and communities in the Western Desert. Berber as a language, also known as Tamazight, belongs to “the Afro-Asiatic language group, which embraces ancient Egyptian and Semitic languages.” Despite the connection, Siwah is not as closely related to other Berber languages.

Though language is not the only thing that defines the Siwi.

Their town is walled, and their villages are recognizable mud-brick, separate from the whole, with patriarchal dynamics ingrained into their intra-group politics. The majority of Siwi are Sunni Muslims, though many still adhere to traditional belief systems, observing pre-Islamic customs. Interestingly, Siwa has a patron saint (Sidi Suleiman) whose tomb sits beside a new mosque in the center of town.

Present-day Siwa has nine Siwi tribes in total: three Western tribes and six Eastern tribes. Their central town—an unmissable enclosure—separated itself organically into a West-East split. The Western tribes are Shihayam, Awlad Musa (Sons of Moses), and Sarahena. The Easterners are Zanayn, al-Hadadin (the Blacksmiths), Lehamudet, al-Jawasis (the Spies), Sharameta, and Aghurmi.

Although considered a minority on Egyptian soil, the existence of the Siwi is common knowledge among locals, and with the influx of tourism, insight into their communities has been on a steady incline. Still, it is important not to overly romanticize their existence; the Siwi’s reality as isolated and tribal has manifested several issues, including risky separation from state.

While Cairo remains in control of basic necessities such as water and electricity, any and all issues present are often overseen by the tribes themselves. Traditional processes are often favored over lengthy, costly, and often discriminatory court proceedings.

Additionally, despite Siwah being the predominant language spoken—and in some cases, the only language—Arabic is often imposed in all forms of legislation and schooling. Reasonable as it is to assume an Arabic-speaking country must speak Arabic, the lack of infrastructure surrounding the Siwa Oasis has prevented integration and continues to be a disconnect that severs the Siwi from Cairo’s linguistic, cultural, and political philosophies.

Regardless, it is reasonable to admire the Siwi for what they are: a colorful, enigmatic facet of Egypt prior to its Arabization. They are a raw, and unfiltered observation of how culture can simultaneously persist against all odds and evolve to survive.

Comments (6)

[…] مصر ، من مصر القديمة معبد آمون إلى قلعة شالي بسيوة قبائل البربرالذين يعودون إلى القرن الثاني عشر. اليوم ، غالبًا ما […]

[…] range of Egypt’s history, from ancient Egypt’s Temple of Amun to the Shali fortress of Siwa’s Berber tribes, who date back to the 12th century. Today, tourists of the desert paradise often go to enjoy desert […]