If only the present reality exists, and if we can only see and experience the present reality, then how is it possible that we can also be conscious of the past, the present and the future as though they are organized in a particular sequence?

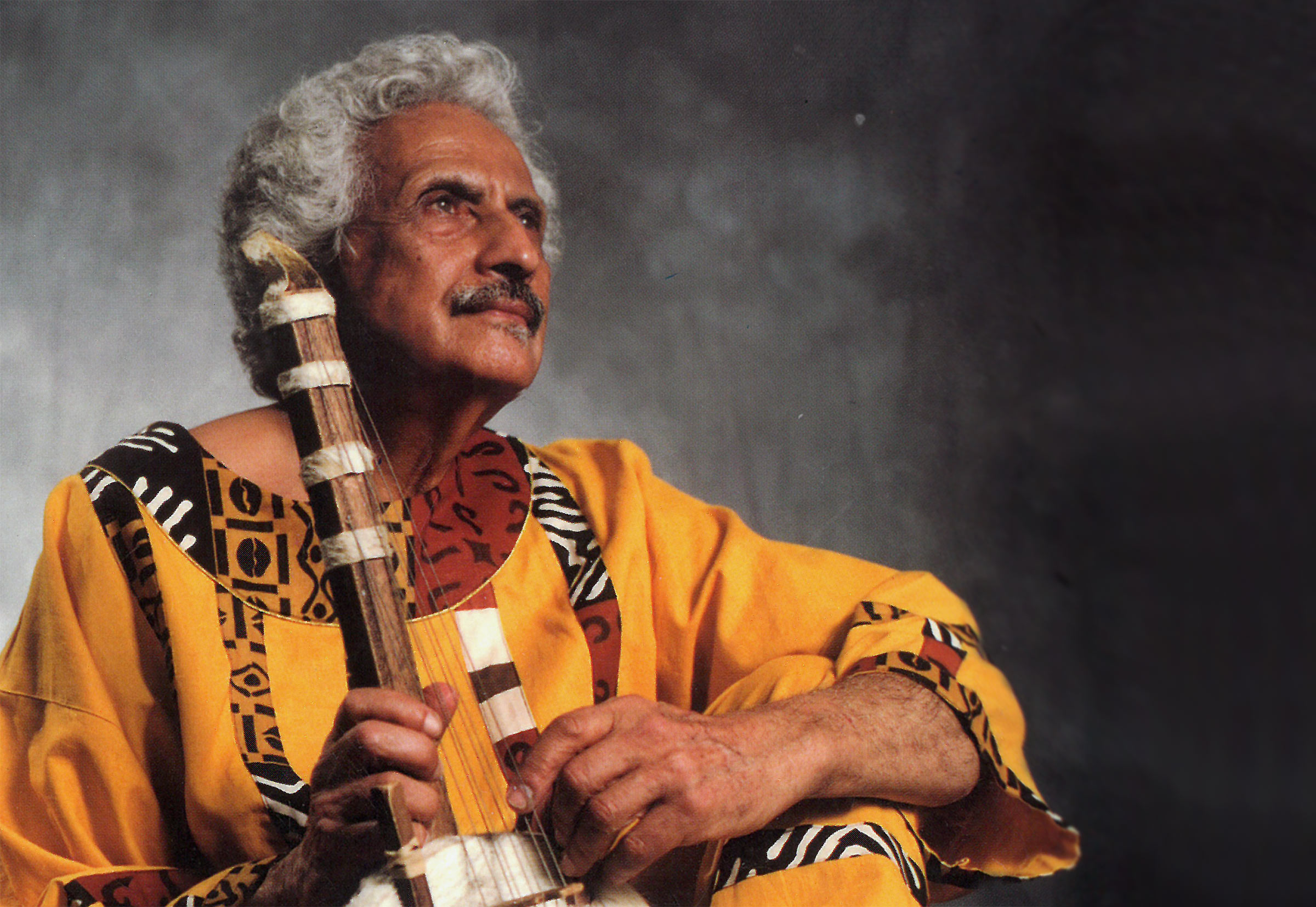

This question did not just ponder philosophers, but also musicians like Egyptian-American Halim El-Dabh, who is famously known as the “father” of electronic music. As per a 2021 article in the Derivative, a Beirut Arts Center bi-annual publication, the author Joe Namy explores El-Dabh’s relationship with music as one akin to his relationship with the universe; using music as a tool to explore transcendence and the state of being deeply immersed in a ‘stream of consciousness’ where the past, the present and the future are flowing harmoniously.

For El-Dabh, music created more than just sound, but also movement, embodiment, and political expression. It can awaken inner voices and suppressed identities, and reverbate waves of energy that synchronize with the rhythm of the universe. “I wanted to find the inner sound, that vibration that’s always necessary for transcendence. That’s what the whole idea of electronic music is. You have a recording and you go inside the recording to find the hidden meaning,” he once said.

In an attempt to ‘decolonize the ear’, El-Dabh was a pioneer in using sound as a cultural and political weapon against cultural homogenization. In her research on Halim El-Dabh’s music, music journalist Kamila Metwaly refers to the political connection between sound and the body, and how El-Dabh’s ‘Ta’abir Al-Zaar’ — one of the earliest known electronically composed works — aimed to translate the lived experiences of communities in Egypt and explore the politics of listening.

Through the eyes of Metwaly, El-Dabh’s pioneering work and Pan-African vision explored the voice-body-mind nexus and the potential of sound, and of music, in challenging the colonial and oppressive histories of music.

His work was an “intimate experience with people” and the local population, Michael Khoury writes in ‘The Arab Avant-Garde: Musical Innovation in the Middle East’. El-Dabh used audio recordings of different sounds from daily Egyptian life in his music that stood in contrast to Western globalization of world music, which homogenized cultures rather than embraced their own unique sounds.

From Agriculture to Electronic Music

Born in El-Sakakini, a small district tucked away in Cairo, El-Dabh’s life was surrounded by all kinds of music from when he was very young. He recalled noticing just how much communities in Egypt were deeply connected to music, with the example of the subuh (naming) ceremonies and how they influenced his understanding of the healing and communal elements of music. “As I listened to the sound of music around me, all the negativity was strained away from my body exposing me to the new world,” he once said.

Inside his own household, music was an unavoidable feature in his family’s life.

In his interview with ethnomusicologist Laurel Myers Hurst, El-Dabh noted that his parents, brothers and sisters all played musical instruments, such as the piano, lutes, violins and drums. His brother Adeeb played piano and violin, his sister Bushra played violin and an Egyptian lute, and all his cousins played lute. The family would often host many musicians, and his own father often sang while his mother played an old instrument similar to the accordion.

El-Dabh’s musical soul first developed after he started playing the piano. Imitating his brother, who was a well-known pianist on the radio at the time, El-Dabh was deeply inspired by his brother’s skills, which made him aspire to grow as a musician and follow in his footsteps. When he began to have his own audience as a child, his interest in music grew, so much so that by the age of 11, he began writing his own music.

In 1932, El-Dabh’s brothers brought him to a concert at the historic 1932 Conference on Arabic Music in Cairo, which first exposed him to music documented on a wire recorder — a device he would later use to manipulate sounds and grow to become one of the earliest pioneers of electronic music.

Yet his maturity as an artist reached its peak in the 1940s, when Egypt, and the rest of Africa, was witnessing a strong movement that demanded independence from British and French colonialism. After graduating with a degree in agriculture in 1944 from Cairo University, El-Dabh developed his own ideological and political views, which would later influence his Pan-African view of music that emphasizes decolonization and self-determination of African nations.

His first exposure to electronic sound devices was in 1943. Studying pest control as an agriculturalist, El-Dabh wanted to experiment and test whether sound-emitting devices could distract the behavior of beetles that attack wheat, corn, alfalfa and beans. He would scratch the rods together to discourage the bugs, and used mirrors and sound to keep bees from flying away from their hives.

From experimenting with beetles and bees, his interest in electronic music grew organically during his travels to villages in Egypt, where he advised farmers on crop-growing strategies. Throughout his travels, he came into close contact with the lived experiences of the local people and how they engaged with music and created their own sound. He began looking into folk traditions and ceremonies, and used wire recordings to manipulate the sounds of the villages’ environments.

Remarkably, and from the small villages in Egypt, El-Dabh created the first known work ever composed by electronic means, known as the Expressions of Zaar (now known as Wire Recorder Piece). This was even four years before French composer Pierre Schaeffer later gained global recognition for his 1948 composition, Cinq Études des Bruits. Based on recordings of women chanting at an Egyptian healing ceremony, El Dabh disguised himself as a woman in full niqab to access the ceremony, and then recorded the input of the Zaar women’s voices to create overlapping tones and different sounds.

After performing at Cairo’s All Saints Cathedral, he received an invitation from the US Embassy in Egypt to study at the famous Juilliard School in New York. Instead, he chose to study at the University of New Mexico to explore Hopi music, which was a culture of sound that was renowned for its spiritual and healing qualities.

In the United States, El-Dabh went on to gain more fame and recognition for his works, and became an active member of New York’s community of musical thinkers as well as joining one the “Les Six d’Orient”, which represented contemporary composers inspired by Eastern music.

Exploring the relationship between music and body healing, El-Dabh gave lectures at several universities and institutions. In 2005, he gave a lecture at UNYAZI Electronic Music Symposium in Johannesburg, where he explained the healing qualities of music that he experienced during the zaar ceremony.

“These women were transforming sound, in their own way, coming out of their own bodies,” he noted. “That they knew how to transform elements and change waveforms, and change the vibration around their voices. Because, in their ceremony these women were flying, practically, I mean their body was moving out, and they had an enormity of energy, in a sound, basically, a sound characteristic that affects the body, and gives you a kind of healing.”

In the late 1960s, El Dabh was invited back to Egypt by order of former President Gamal Abdel Nasser, which saw him create the Sound and Light Show at the Giza Pyramids, which has become a ritual performance ever since 1961.

An artist like no other, and a curiously spiritual thinker that sought to find the hidden meaning of the universe through music, El-Dabh’s legacy reminds artists to explore music through cultural, spiritual and political lens, and more importantly, to capture the sounds of different local environments and truly engage with the local people. In short, El-Dabh is not just the founder of electronic music, but also pioneered a more democratic and local sound that reflected the expressions and identities of all cultures.

Comments (0)