Woven intricacies of oriental arabesque awaken the memory of a bygone area, where decorative ornaments needled mosques, palaces, and domes with unique wooden motifs.

Arabesque, as dubbed by scholars of geometric art and traditional craftsmen, is a “jewel of arts.”

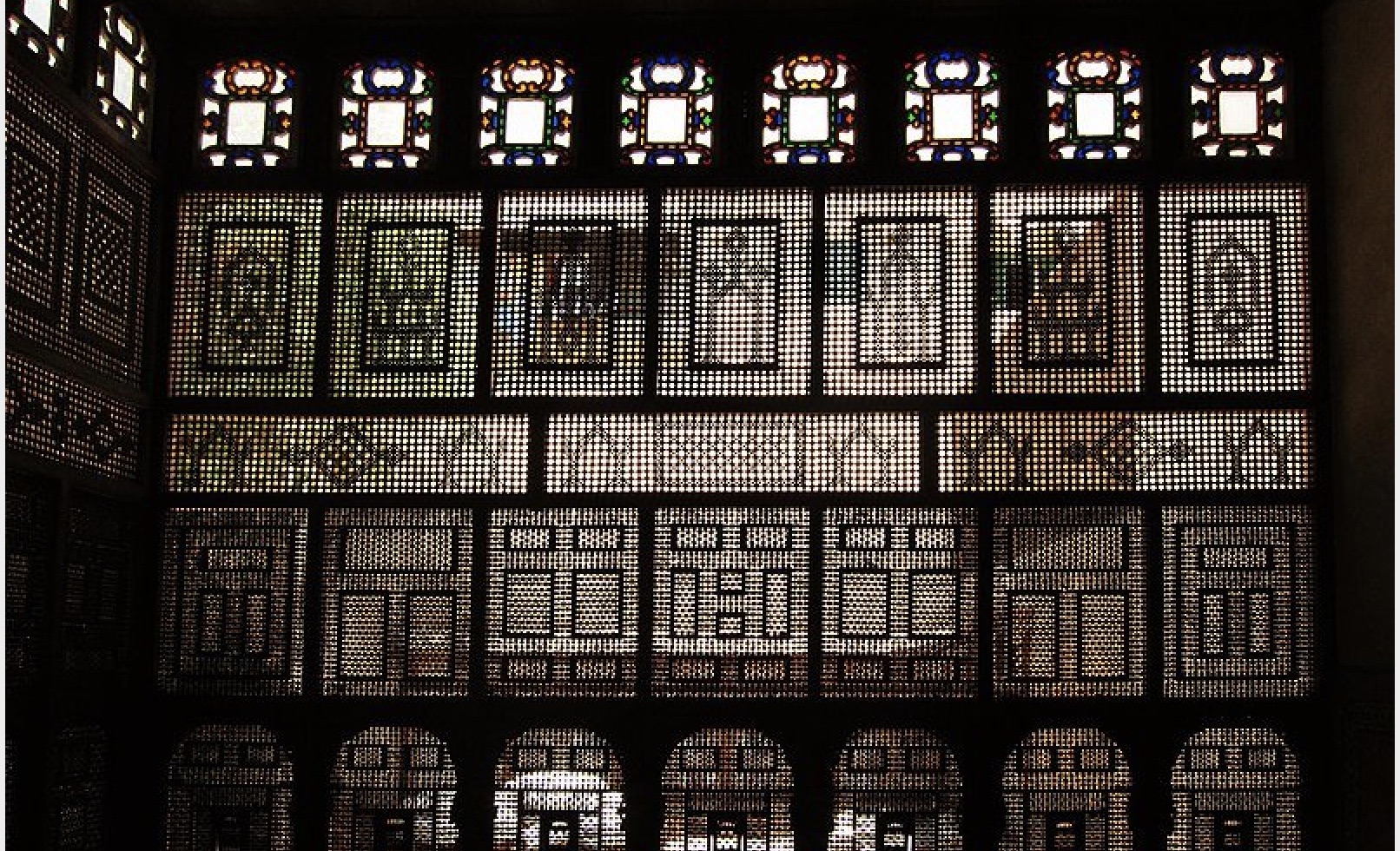

Adorning windows and doors throughout Egypt are the geometrical details of arabesque, an art form used by Islamic artists who sought an alternative to use figurative images of living creatures, which was thought by some as religiously undesirable. As a result, interlacing repetitive patterns that flow in and out of each other created a testament to the gorgeous past.

Arabesque is one of the most emblematic elements in Islamic art; it is believed to have been birthed in Fatimid Egypt, circa 969 A.D. The nascent Fatimid Caliphate fought many wars, where it was forced to utilize wood to make weapons and military equipment. The remaining wood that was left behind was sent to craftsmen and carpenters, who would then transform it into geometrical shapes.

Breaking the rigidity of wooden art, it laces vegetal designs of tendrils and leaves into motifs that exude continuity and immortality.

The art further developed during the Abbasid period, a time when science paved the way for an increased knowledge of geometric and arithmetic shapes. Arab artists did not curate new shapes, but rather, they used the readily available patterns in unique ways that were suitable for the fundamentals of Islamic art.

In the 19th century, arabesque transcended beyond the borders of Egypt and into the Ottoman Empire. Sultans of the Ottoman Empire commissioned Egyptian arabesque craftsmen in Istanbul to decorate their homes and palaces.

Egyptian artisans often use the finest timber, camphorwood and sandalwood, in creating the arabesque pieces. The versatility and adaptability of the arabesque allowed it to exist not only within the furniture industry, but it can also be found adorning columns, minbars – which is the podium for the imam of the mosque, positioned in the direction of Mekka – mashrabiyas – which are mock windows that allow those inside to see the outside without being seen – windows, and doors.

It is a sacred art, paying homage to the peaceful nature of Islam, where the sunbeams seep through, allowing warmth and tranquility, not paying attention to the chaos of the outside world.

Decking some of Egypt’s most iconic corners, Khan el-Khalili, Wekalet el-Ghouri, and el-Gamilya neighborhood, Egyptian arabesque has become a tourist attraction in itself. Although it’s an art at risk of evanescence, it remains etched in Egypt’s history.

Comments (0)