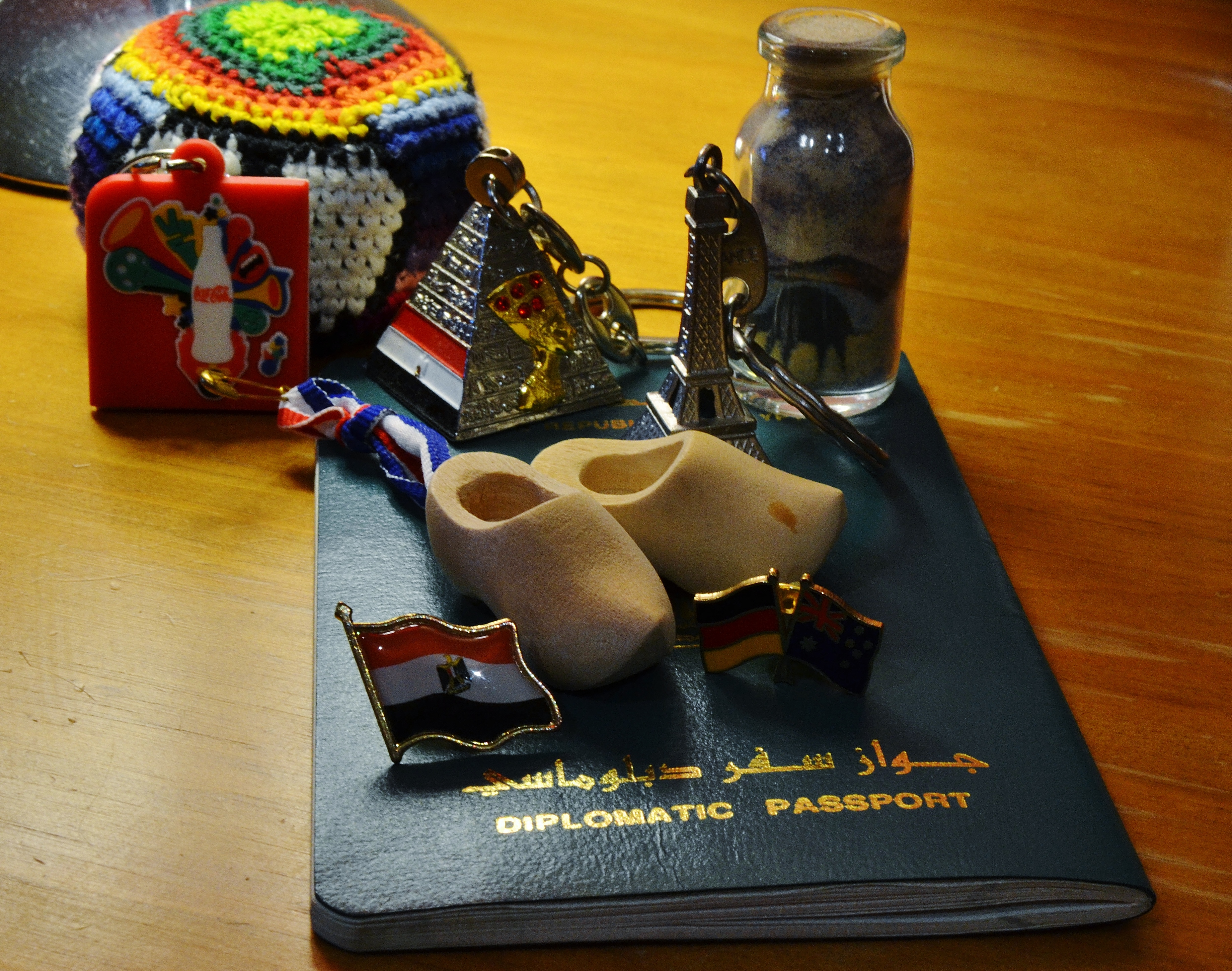

Sipping expensive cocktails and nibbling on exotic fruits and cheeses at extravagant events in the presence of Presidents and Prime Ministers, Kings and Queens, are all part of a hard day’s work in the diplomatic service. Or at least that is what many Egyptians like to believe.

“It sounds glamorous, exciting and even romantic,” says 21-year-old Myrna Abbas, the daughter of an Egyptian Ambassador. “But in reality, many fail to realize that though our lives seem so desirable, the journey to how we became who we are, and the obstacles we have faced are far beyond what many people believe.”

These misconceptions are widespread in Egypt. During a parliamentary session on May 21st, members of parliament condemned the Foreign Ministry’s budget, claiming that diplomats and their families are being paid extraordinarily high “just to fly first or business class…and live in lavish mansions across the globe.”

In reality, diplomatic life for Egypt’s 980 diplomats is far from glamorous. For every posting in New York and Paris, there are many more in obscure and desperate cities like Mogadishu and Kabul. Safety and services such as functional hospitals and well-stocked supermarkets are some of the basic aspects of life that many Egyptians take for granted but are not always available for diplomats.

Sherif Higazy, the son of an Egyptian Ambassador who has lived in seven countries across five continents, believes that the diplomatic lifestyle is often misunderstood.

“It’s tough to see it [diplomatic life] as a privilege,” says Sherif who visited Srinagar, a city close to the highly disputed Indian-Pakistani border and often faces insurgency attacks. “If you live all your life…constantly moving, constantly travelling, you grow up feeling like it’s the default. It’s only after moving out that things seem like a privilege retroactively…travelling the world becomes an exercise in frustration.”

Movies like Lethal Weapon 2, The Constant Gardener and The Year of Living Dangerously portray a relaxed lifestyle, but Myrna, who has lived in countries as diverse as Colombia, Saudi Arabia, Canada, and Italy, says that many of the difficulties that diplomatic families face are often not known to the public.

“When we first arrived in Colombia’s airport it was so dangerous we had to rush to the car,” explains Myrna. “Crime was big in Colombia…but that doesn’t mean that other countries did not have their problems.”

Egyptian diplomats and their families move to a new country every four years, and the relocation often takes a toll.

Mostafa Rizk, 20, has lived in six different countries ranging from Namibia to Italy and says the greatest challenge he faced was having to adapt to different education systems.

“I’ve switched between three or four different school systems in my lifetime. In every country I work hard…but then when I transfer, I will often find that I have to jump a new set of hurdles to get ahead in my new environment,” concedes Mostafa, who currently studies computer science in Melbourne. “But I’ve learned to adapt and the education I got abroad is in many respects better than what I would have gotten in Egypt.”

As an art student in Milan, Myrna believes that maintaining relationships with friends and extended family has been a tough issue to face. “I’ve been programmed to meet people, knowing that I’ll be leaving them a few years later. I envy people who have had childhood friends that they’ve grown up with for 20 years,” says Myrna. “But it’s still wonderful to know that I have so many friends around the world…and thanks to modern technology keeping contact is very easy.”

Despite these obstacles, children of diplomats reveal that they often embark on remarkable journeys that have enriched them in ways that are immeasurable.

“I know I would not have been the same person had I not been a diplomat’s kid,” says Myrna. “Due to the fact that I’ve lived in many countries, I carry a piece of all of them with me…and have learned to accept other cultures.”

For Sherif, who is today studying film and television production in California, travelling has allowed him to develop a different perspective on the world.

“Nationalism I just don’t buy. After travelling the world and becoming extremely close to folks from all across the globe I don’t understand why powerful nations have become such an unshakeable tenant of the international system.”

Yet, it is transitioning back to Egyptian culture every four years that has been especially challenging for diplomatic children. Research done by sociologists into third culture kids – people who have spent a significant part of their developmental years outside their parent’s culture – indicates that they tend to feel like a minority group within their own passport culture.

“I’m usually expected to be a sissy or soft from life in a comfortable environment. I’m expected to be less religious than your average Egyptian and to be concerned with matters of fashion and style and live a very hedonistic life style,” says Mostafa.

However, despite constant relocation and challenges faced upon repatriation, diplomatic children say they have developed a special connection to Egypt.

“The most common assumption is that diplomat kids are completely detached from their Egyptian heritage or culture and claim they are from countries other than Egypt because they are ashamed of their true origin,” says Myrna. “It is needless to say that this could not be farther from the truth. Egypt is and will always be my real home.”

Comments (10)

Same challenges as military families face. These jobs of parents defintiely impact the whole family…..namaste….Anne

Reblogged this on Oyia Brown.

That really captures the spirit of it. Thanks for posting.