In a garage behind a row of parked cars sleeps Mostafa near a pile of litter left behind by a street dog and its newborn puppies.

A couple of dusty blankets and pieces of cardboard serve as his bed. He earns his money as a parking attendant, shoe shiner and handyman; anything that will make him a few pounds.

A little over a year ago, the 25 year old university graduate was living with his parents in a working class neighborhood in Cairo. He worked as a salesman in an electronics shop and spent his weekends with his friends at the local tea-house.

In the summer of 2014, he and a friend went to a hotel bar to have a beer. Two hours later, he was locked up in a police cell, handcuffed and with a black eye.

“I was charged with being a homosexual,” he explains. “Apparently, that hotel bar is a meeting place for gay people, and that evening, the police raided the bar.”

It took Mostafa until the beginning of this following year to get released, thanks to a local human rights organisation. However, while the charges against him were dropped, his parents and friends never came to visit him during the time he spent behind bars. When he returned home, his parents refused to open the door. Furthermore, he lost his job and his friends no longer wanted anything to do with him.

“In the blink of an eye, I lost everything I had,” he mumbles, obviously still in shock over what has happened. “My life as I knew it was over.”

The fact that the charges were dropped didn’t matter. “Everybody thinks I am gay now, so I’ve become a pariah. My own brother doesn’t even answer my phone calls.”

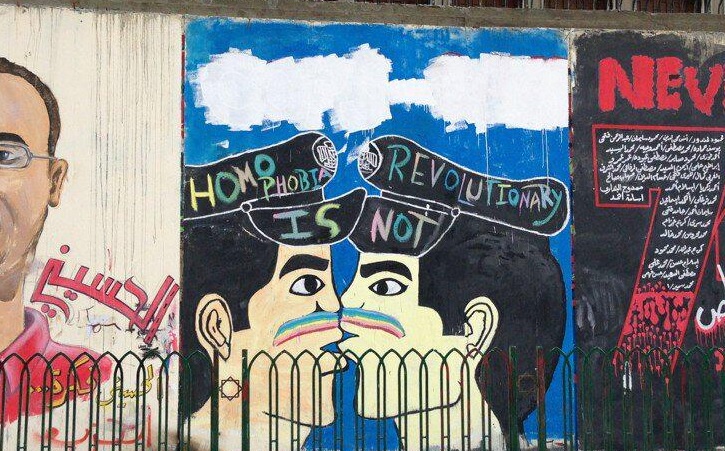

Since president Mohammed Morsi was deposed in July 2013, at least 170 people have been put in prison for allegations and accusations of homosexuatlity. Later under the new leadership of president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the situation for homosexuals, if anything, got even worse, leaving them more oppressed than ever before.

In Egypt, homosexuals are mostly thought of as ‘sick’ and ‘immoral’. “I would rather have my brother have cancer than be gay, because cancer can be cured,” says Khaled, a 28-year-old TV reporter.

Meanwhile, Walaa,26, a receptionist at a language institute, thinks it would help if the media dedicated more time to covering homosexuality, so people would get a better understanding of how great the danger of this ‘immoral disease’ is. “The degeneration of society is to blame; young people no longer have morals,” she thinks.

On another note, Mohammed and Mahmoud, who both still live with their parents, have been together for four years behind their families’ backs. “My family is like the American army,” Mohammed explains. “Don’t ask; don’t tell. My mom is a liberal and well-educated woman, but for the of her peace of mind, it’s better that I don’t openly confess [my homosexuality].”

On the other hand, Mahmoud’s family refuses to acknowledge his sexual orientation all the same, and preferred to act in denial. “They think this is some sort of a phase I am going through, and that in a few years’ time, I’ll get married and start a family,” says Mahmoud.

However, opposite to his family, Mohammed’s coming out of the closet cost him losing all of his college friends. “They all cut me off afterwards,” he says.

“When there are other people around, we act like regular friends,” Mahmoud says. “Sometimes, people will comment ‘wow, you guys spend a lot of time together,’ and then we make a point of not seeing each other for a few days. As soon as someone gets suspicious, we start avoiding that person.”

According to Mahmoud, it’s logical that the current regime cracks down harder on the LGBTQ scene than their more religious predecessors -the Muslim Brotherhood. “They are trying to maintain this image of being more religious than the Brotherhood. Besides, the Muslim Brotherhood had plenty of other problems to worry about than a few gay guys.”

What troubles Mahmoud greatly though is how people meddle in each other’s businesses the way they do. “I just want to be left alone. We’re not bothering anyone, so why bother us?”

Mohammed only has one wish for the future, and that is to get out of Egypt with Mahmoud as soon as possible. “I love Egypt, but I can’t be myself here. I want to be able to be who I am -out of the closet- without endangering myself. The only way I can do that is by having a European passport.”

However, back at the garage, Mostafa looks to the past instead of to the future. “I would give everything to be able to go back in time and spend my evening at home on the couch instead of in that bar.”

Please note: upon their requests, all names have been changed to protect the privacy and safety of those interviewed

Comments (7)

:'(

Horrible, nobody deserves to be treated this way.