Whenever we walk the streets of Cairo or any other city, for that matter, how often do we stop to ask ourselves, “Why is this street called XY?” Or if we do hear or see a street name, what associations spring to mind? Why are certain streets in Zamalek named after other countries (Brazil Street) or cities (Berlin Street)? Why do some sources refer solely to Tal’at Harb Street, while others might insist on adding Seliman Basha Street, its former name? And do we ever consciously reflect on the meanings of specific place designations such as ‘bustan’ (‘plantation’), ‘darb’ (‘side street’), ‘manshiya’ (‘housing compound’) or the specific titles of Basha, Sheikh, Duktur, Beih that grace many of the capital’s street signs named after individual figures?

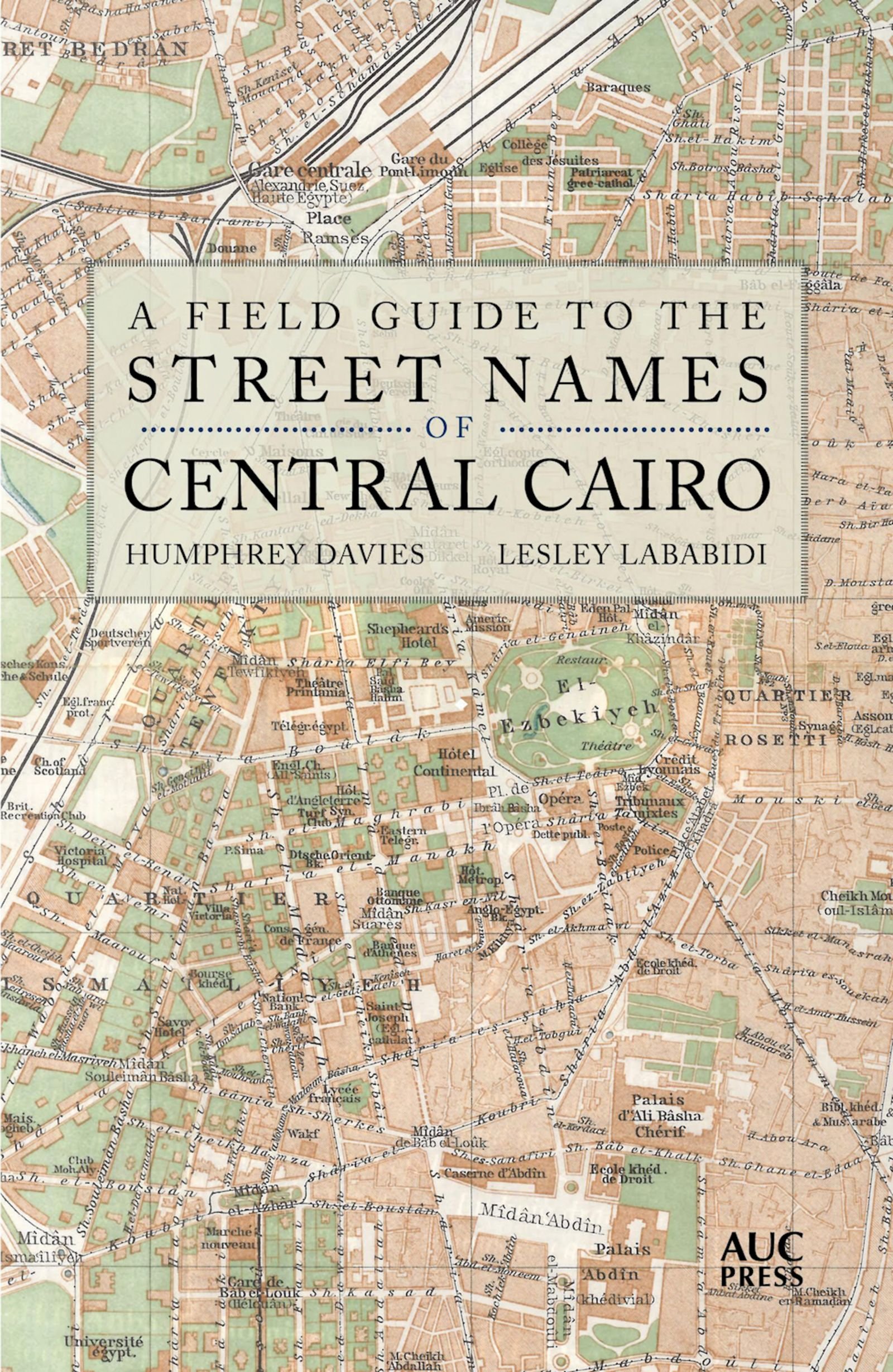

Published by AUC Press, A Field Guide to the Street Names of Central Cairo (2018) provides thoroughly researched and original answers to these questions and more. Although it starts out with the following disclaimer:

‘This is not a guidebook, or at least not one that will help the reader to get from A to B (let alone from A to Z).’

Collaboratively written by renowned translator of Arabic literature, Humphrey Davies and author of multiple travel and Cairo-related books, Lesley Lababidi, the ‘field guide’ provides not only a valuable map in written form, but ambitiously documents Cairo’s modern history through its street names.

Street names generally expose aspects of a place’s history; while they are relevant and used in our daily present, they remain equally symbolic of past times. The are both functional and carry historical and cultural significance, especially the latter two of which this book attempts to further unravel.

Defining its object of interest as ‘every officially recognized thoroughfare or public space’, the main segment of the book entitled ‘The Guide’ comprises a detailed alphabetic list of 607 current street names of Cairo, followed, where applicable, by former or alternative renditions (a total of 377).

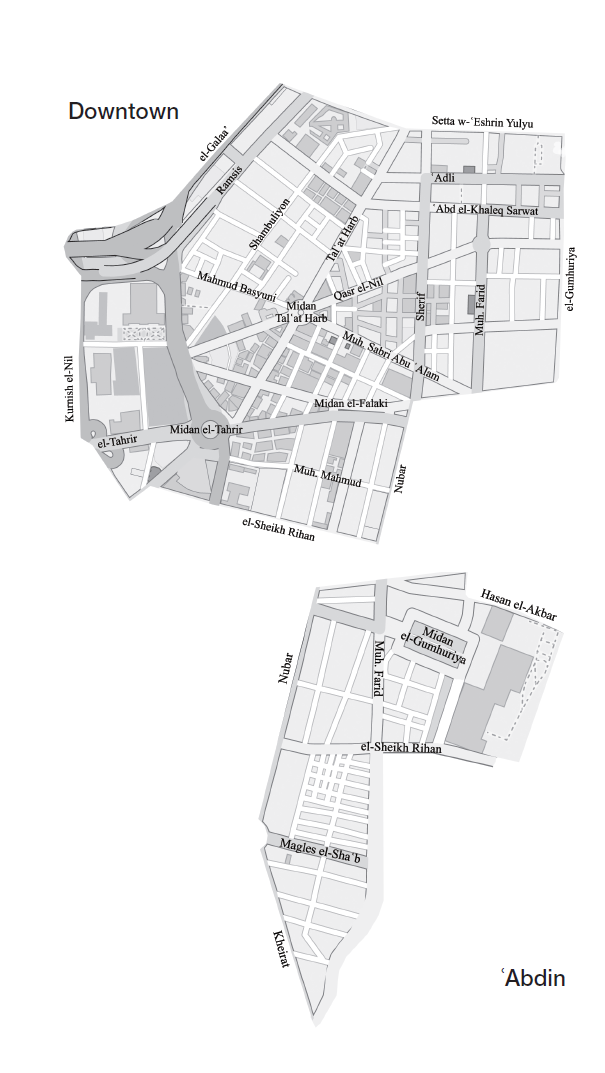

The book’s coverage area is central Cairo, as its title suggest, or what is concisely historicized in the introduction as ‘Greater ‘Esma’iliya’, the area of the city that was created and modernized in the late 19th century under Khedive Esma’il’s command.

To facilitate orientation, the authors have furthermore divided this broader area into 10 districts like Downtown or Garden City, for which individual maps are provided prior to the guide itself.

The significant changes that have occurred over time are also noted in the introduction, whereby ‘Abdin, for example, ‘was, in the mid-nineteenth century, an area of ponds and unplanned neighborhoods.’ At the same time, the book takes continuities into consideration, like the observation that ‘el-Zamalek remains arguably the city’s most prestigious neighborhood.’

The flesh of the book comprises a detailed street listing, with all names accompanied by descriptions of what or whom they are named after as well as the dates at which they supposedly changed. Here, the reader comes across many instances of ‘perhaps’, ‘probably’ or ‘unidentified’, testament to the inevitable speculation involved in this book project – basically the impossibility of always being able to provide definite and fixed information about the streets’ histories. The authors are clearly aware of these challenges and limitations, as they reveal in the introduction, humbly pointing out that ‘given the ambiguities and gaps referred to above, this book must be seen as a work in progress.’

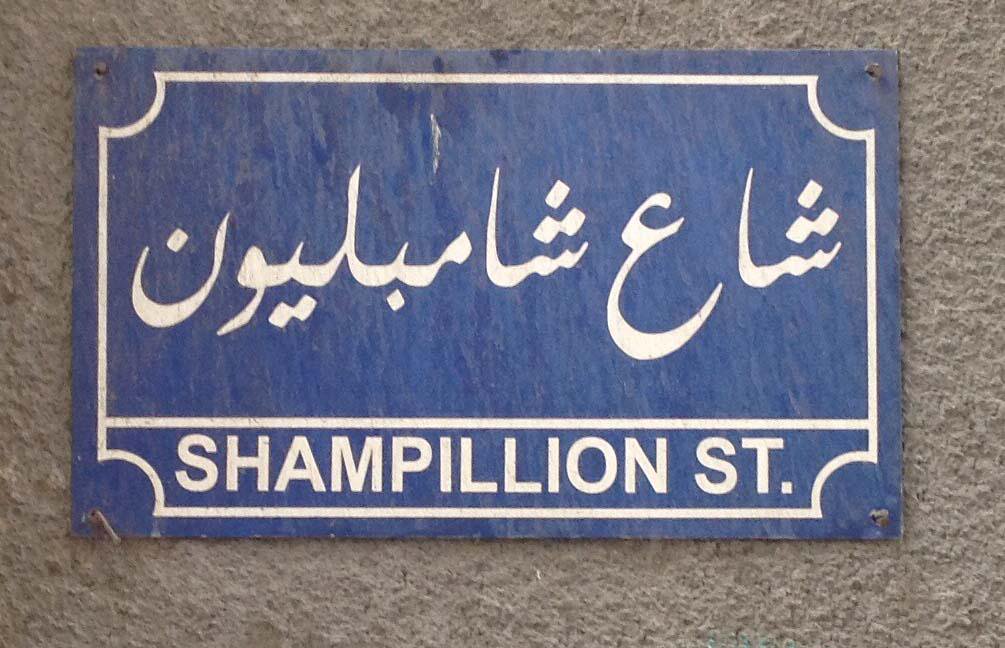

The countless street names need of course to ultimately be examined by curious readers themselves. While many of the figures inscribed in Cairo’s street names are famous and known to the average Egyptian, other readers are likely to be fascinated by the sheer amount of history evoked by an individual name.

Certain streets witnessed and now commemorate Egypt’s most significant historical events and its successive rulers, while many others contain landmark buildings that are mentioned in the book. Downtown’s Share’ Adli, for instance, is notably the home of Cairo’s central synagogue, Sha’ar Ha-Shamim synagogue, which was built in 1902. Besides, as the guide details, ‘from 1934, the street was home to the Turf Club, symbol of British domination, burned by a mob on 26 January 1952.’

Other times, we go as far back as the Ayyubid dynasty, with Zamalek’s Shagaret el-Durr, named this way since 1913, commemorating Egypt’s only female Muslim ruler: ‘Shagaret el-Durr was the wife of el-Salih Ayyub, last Ayyubid ruler of Egypt.’

With a flair for mundane details, who would have thought that bustling El-Sherifein Street Downtown was named ‘after two unrelated men each of whom bore the name Sherif and each of whom had a mansion on this street’

Professions and commerce appear to be a further common source of inspiration for street names, with El-Falaki street named after Mahmud Ahmad Hamdi (1815-85), ‘the Astronomer,’ who lived on the street, or the Kudak Mamarr, (‘Kodak Passage’) owing its name to Egypt’s headquarters of the Kodak Company established there in 1940.

Multiple pages are dedicated to street names after figures with important titles: dukturs, shahids, sheikhs. And foreign presence has also made its mark on the maps of Cairo, ‘El-Khawaga’ street (‘Foreigner’s Side Street’) being a prime example. As the book explains, Khawaga means ‘(non-Muslim)’ foreigner’ and was also formerly a title of respect used of Coptic merchants.

This book will undoubtedly continue to be topical for many years to come, being at once a valuable guide and historical document. It makes the reader not only want to re-investigate Cairo with these newly acquired facts in mind, but want to pay attention to the same in other cities. Finally, the book conveniently closes by leaving hungry readers with a comprehensive bibliography of printed and online sources.

The American University in Cairo Press has published both this book as well as many others by the same authors. It is the leading English-language publisher in the Middle East and largest translator of Arabic literature in the world.

Comments (0)