Shadia, Samia Gamal, Soad Hosny, Hind Rostom, and Nadia Lutfi…these are names of female actresses and dancers that evoke contradicting feelings for many Egyptians today. While they are highly praised and watched for their art and performances on screen, their charm, beauty and bold sensuality is often seen as dangerous and threatening to society’s morals. They were, in other words, the ‘femme fatales’ of Egyptian cinema – a concept that is still hard to define and understand when it comes to explaining women in art.

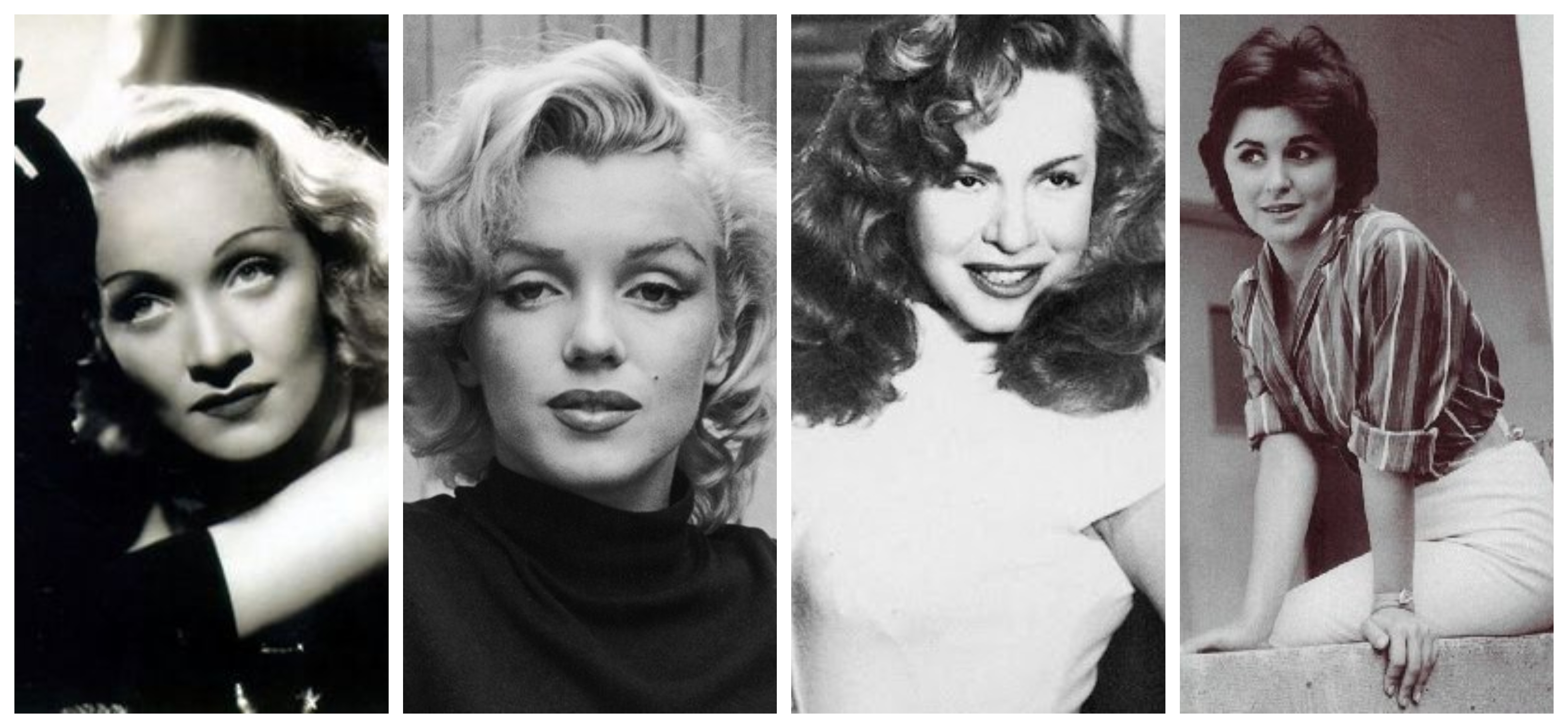

The ‘femme fatale’ is most commonly defined and known to be the popular female actresses in Hollywood, who constructed and propagated this fantasized female figure in cinema and popular culture. It refers to the sensually dangerous woman who posed a threat to the power of the man, whose charms often lead lovers into dangerous and deadly situations, and who is also a morally ambiguous figure.

It is a feminine ideal that seems both emancipating and oppressive, allowing the female actresses to be in control of their own sensuality and character, and yet constraining them under the roles and imagination of their male directors. For instance, Marlene Dietrich’s entire legacy has long been attributed to the work of her so-called “creator,” director Josef von Sternberg, who directed her in eight prominent films.

The question that is often posed is: Is a femme fatale a product of the male or female imagination? Is she empowering or stereotypical? Progressive or regressive?

The truth is that there has never been a coherent answer. Though she captivates the audience with her glamour and allure, one can still sense elements of vulnerability, pain and exploitation.

From Marilyn Monroe’s tragic barbiturate overdose to Soad Hosny’s death after falling from the balcony of an apartment in London, it is clear that these women still faced the horrors of being in a patriarchal and male-dominated industry. Marilyn Monroe, for example, found it difficult to get away from the stigma of the beautiful blonde and simply be considered an object of pleasure, failing to affirm herself as a respected actress.

In fact, they – the femme fatales – represent the contradicting reality of many women today – they all hold more than what they reveal, and though they climb to great status in their professional work, they still have to confront sexism and prejudice that undermines their work and social position in society.

Hanson and O’Rawe observe that the femme fatale is both an “entrenched cultural stereotype and yet never quite fully known: She is always beyond definition” as she “evokes more than she describes”.

According to Antonio Marcio da Silva, the femme fatale can be seen beyond the single definition imposed by Hollywood, and does not need to be restricted to American and Western films. She can represent many different identities and characters, and evoke symbols of empowerment for various kinds of people and societies.

In other words, the femme fatale is ever evolving and travels across time and different continents. She does not need to be sexually dangerous, beautiful, young, or American, nor limited to one film genre, but can appear in a variety of roles and contexts.

In Egypt, Shadia played the story of Esmat, in Merati Modeer Aam (My Wife is the General Manager), who gets promoted at the same company where her husband works and becomes his manager, presenting an important role model of the hard working woman who aims to succeed in her professional woman. Lobna Abdel Aziz played Ana Horra (I am Free), a young girl who goes to college and gets involved in politics, sharing the lesson that the ultimate freedom for her is to be free as an individual. Soad Hosny played other roles in more political films such as Ala mn notlik Al-Rosas (Whom should we Shoot?) and embodied female characters struggling with poverty and war, such Ehsan in Cairo 30.

Even their sensuality was often more a result of their artistry and character rather than the vision of their male directors, evoking qualities of femininity instead of degeneracy. When Rita Hayworth plays the sensual Gilda in 1946, she looks serious, in control and cheerful, performing her character for the general audience and not just for the male gaze.

The main goal is to recognize these women as artists just as other women are recognized for their profession, and for them to still be remembered for their work. To downplay their role would mean to ignore the sexism and exploitation that they have had to face in the industry, and their attempts to climb above it. In short, it is to erase their own individuality.

For instance, despite being one of the greatest icons in the golden era of Egyptian cinema, Hind Rostom reportedly only received Egypt’s State Merit Award in Arts in 2004, which she rejected with a quote,”the award came too late, I’m not placed on the shelf for them to pick me whenever they want.”

Indeed, women in art and cinema are often placed on the shelf for society to pick and watch whenever they want, and are never truly honored for their artistic performances. Without recognizing them, and without further developing the character and definition of the ‘femme fatale’, women in art will continue to face exploitation, subjugation, and sexism in an industry that is far more impactful and influential than many would like to believe.

Comment (1)

[…] […]