Known to have existed for almost thirty centuries, Egypt’s soul has always been deeply historical. In every direction, and behind every historic building, there is a rich past of people who came from elsewhere and then settled, built and fought for this land. From the pyramids, we see the past of the ancient Egyptians, and similarly, from other iconic buildings like the Sultan Hassan mosque, there is also the past of the Mamluks who, in contrast to what many think, also perceived themselves as Egyptians.

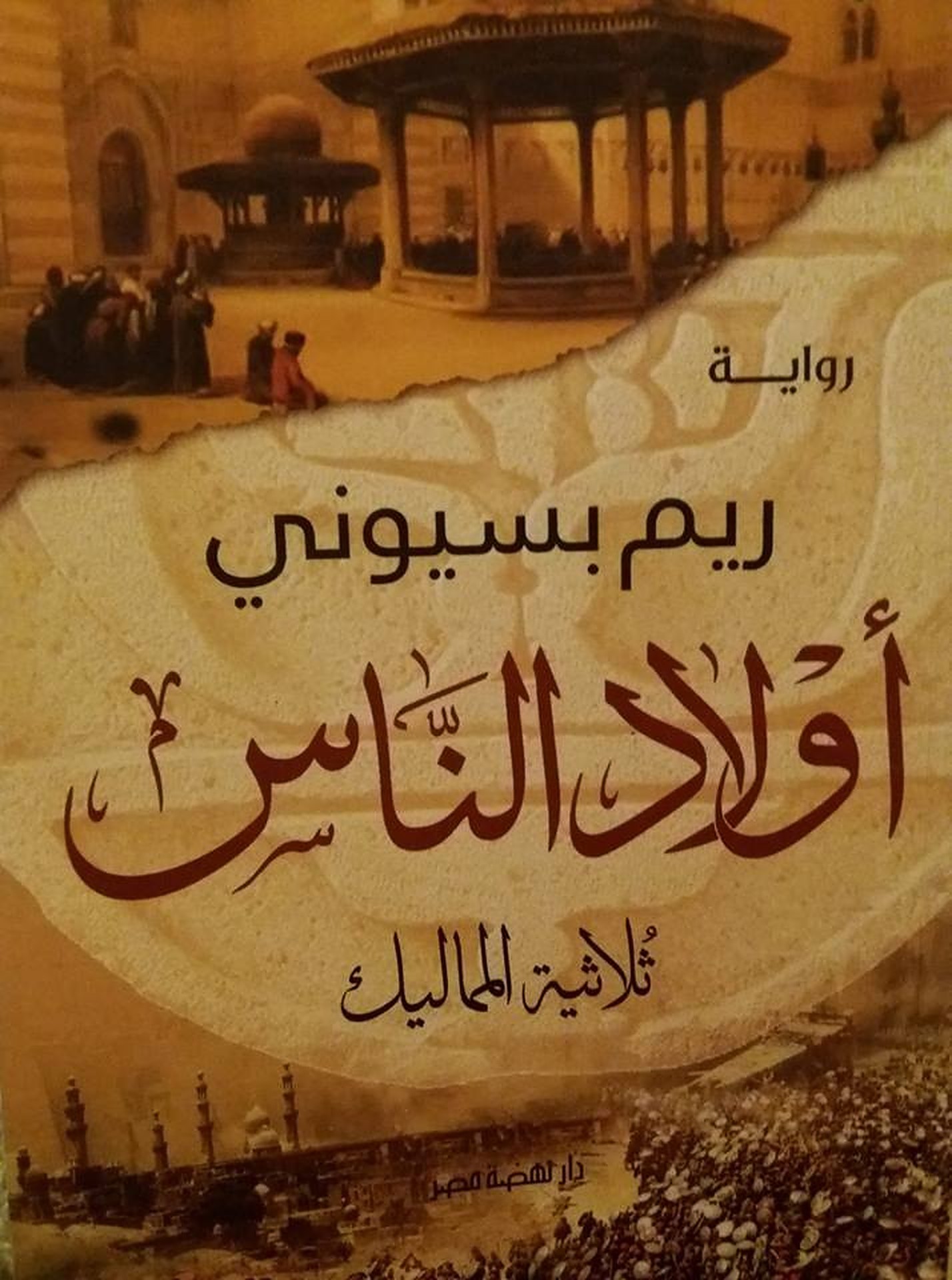

In her new 2018 fiction novel, ‘The Mamluk Trilogy’ (Awlad El Nas), renowned Egyptian writer Reem Bassiouney approaches history with a deeper outlook on the human experience of the Mamluks in Egypt, who originally came as owned slaves and then later ruled Egypt for around 267 years. With her introspective, engaging and gentle writing, Bassiouney introduces new and fresh ideas on identity, history and what it means to be Egyptian.

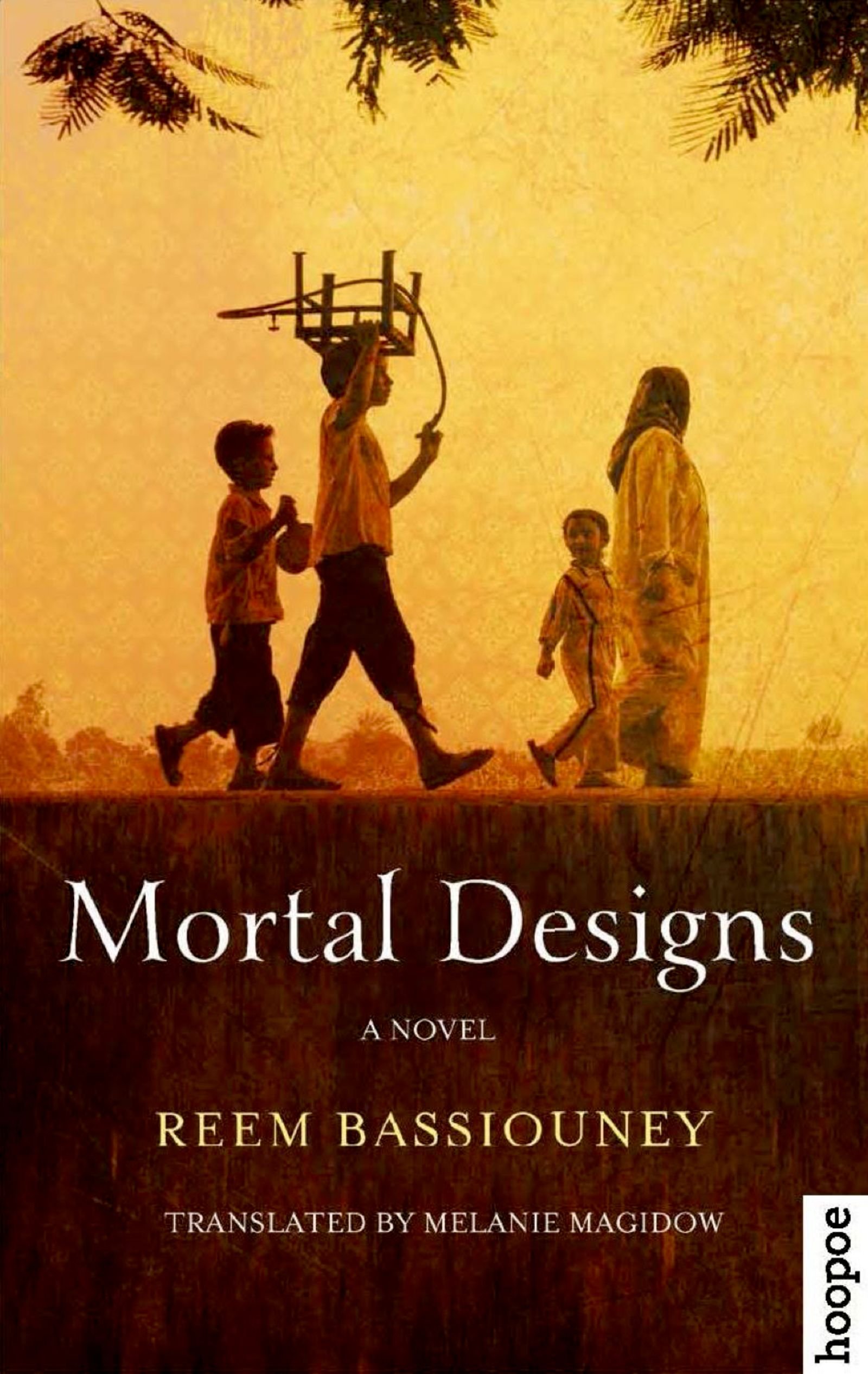

Egyptian Streets sat with Reem Bassiouney to discuss the fascinating trilogy and her views on identity. She is a professor of sociolinguistics at The American University in Cairo, and has written several novels that were translated into different languages, such as Professor Hanaa, which won the 2009 Sawiris Foundation Literary Prize for Young Writers, and Mortal Designs.

WHAT REALLY INSPIRED YOU TO WRITE THIS BOOK? AND WHAT WAS THE PROCESS OF WRITING IT?

It started when I visited the Sultan Hassan mosque in Egypt around six years ago, and I was very interested in knowing the history of that mosque and who built it and when, but I also felt very ashamed because I did not visit it until quite later in my life, and that it is a pity that we as Egyptians don’t know much about this awe-inspiring and spiritual place.

Out of this curiosity, I looked up history books to try to understand more about this mosque, and it took me to a journey of 3 years of research and reading about the history of the Mamluk period in Egypt. After that, I decided in my novel that I wanted to specifically look more at the human side of the Mamluks and understand them as human beings, as in most history books and novels, you will see that the Mamluks are usually portrayed as the oppressors, but their own human experience of being slaves and then becoming rulers later on is never touched upon.

So I started writing thinking it was just going to be one part, an independent novel of about 300 to 400 pages about the social and political background of the Sultan Hassan mosque, and talk about the life of the engineer who built it, who was half Egyptian and half Mamluk. But then after that, I discovered that I did not really finish what I had to say, and I wanted to continue writing not just about the history behind building the mosque, but also what happened after it was built.

So the first part is how the mosque was built, and then the second part is more about what happened during the first dynasty of the Mamluks and how it ended, and what happened to the mosque at that time and how it deteriorated. The third part of the book then looks at the end of the Mamluk period and the invasion of the Ottomans, and how the mosque was a witness to the looting that happened.

On the whole, I was exploring the history of Egypt in just that one place, and how the mosque was a witness to all these changes that happened across this time period. You will also see the change of ideas of the religious scholars throughout the three parts of the book, and the changing events that happen to the family in that area.

SINCE THIS BOOK IS HISTORICAL, DID YOU WANT TO DRAW ANY PARALLELS BETWEEN THAT PERIOD AND MODERN EGYPT?

This is a good question. I did not actually set down to write about the Mamluks thinking about modern Egypt, which a lot of writers did. A lot of other writers spoke about it as a symbol of oppression whenever they wanted to discuss oppression happening in modern Egypt.

But for me this is not the issue at all, I wanted to write more on the human experience, and in the three novels there are love stories between different people and how they somehow managed to negotiate the relationships together despite the differences. So I was interested much more in being sincere in representing both the Mamluks and the Egyptians, and how they interacted daily, married and traded from each other, and also the relationship between the Egyptian religious scholars and the Mamluks. However, I think it is possible to also find parallels, because history always has parallels.

I WANT TO TALK ABOUT THE FEMALE CHARACTER IN THE BOOK, ZEINAB, BECAUSE FOR ME SHE SEEMS TO BE THE MOST STRIKING AND POWERFUL DESPITE THE STRUGGLES SHE FACED. DID YOU INTENTIONALLY WANT HER TO SYMBOLIZE ANYTHING FOR THE EGYPTIAN WOMAN? OR WHAT WAS YOUR IDEA BEHIND CREATING THIS CHARACTER?

Yes Zeinab is a very important and impressive character in her own way. Zeinab, in my opinion, is a symbol of the strong Egyptian woman, because I always look at Egyptian women as brave and hold a lot of inner strength. So I wanted to show how this woman at the time could in fact use a situation of oppression, such as marrying a man that she thinks of as a foreigner, and turn it to make herself eventually the master – of the man, of the situation and of everything around her. Gradually, we see her grow from being a helpless and young immature girl to a mature woman, who starts to appreciate things she did not appreciate before.

AS I WAS READING THE BOOK, I CONTEMPLATED THE IDEA OF IDENTITY AND THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A NATIONAL AND A FOREIGNER, WHY DID YOU DECIDE THIS TO BE ONE OF THE MAIN THEMES OF THE BOOK?

The issue of identity has always interested me throughout my life, as when I left to Oxford University to do my PHD and then later the US, I was always thinking about what it means to be an Egyptian. It’s always important to be away from something in order to see it better, and when I was away from Egypt for a very long time, I started to look at things differently and appreciate more things that used to anger me. I was lucky to have studied society and language, and I have another book called ‘Language and Identity in Modern Egypt’, which is all about what it means to be an Egyptian in modern times and how Egyptians define themselves.

I came to know that identity is something that is very flexible, and the Mamluks in fact saw themselves as Egyptians, and this is for me the most interesting part of the novel because no one before wanted to discuss how the Mamluks actually viewed themselves.

This idea of a person coming at the age of 10 as a slave with no other choice, then has to learn the language and then the religion, which might have not been his own religion in the beginning, and then also learn to have affiliation with this country, is the kind of identity that is acquired and not born. It is something that is extremely important for us Egyptians to understand, because being Egyptian does not mean just being born in Egypt, but it is really about having this feeling that you are ready to fight, live and build for this country. So this idea of who is building, settling and fighting, and for what, is very important.

YOU MENTION THAT YOU LEFT TO STUDY AND LIVE IN THE UK AND US BEFORE, DO YOU THINK THAT CHOOSING TO WRITE IN ARABIC CONNECTS YOU TO YOUR IDENTITY IN ANY WAY?

Yes definitely, language is very important in forming identity, and this is actually what I study. It is a very good question because I studied in English at university, but I was always extremely fond of Arabic and read a lot of Arabic literature. After that, I had seven scholarly books that were published internationally by American and European publishers, and everything that I published was in English.

If you ask me now if I can write an academic article in Arabic I think I would do a very terrible job, however, since the beginning I experimented writing fiction in English, but I felt that I couldn’t express myself in the same way. There is something in my native language that just liberated me, I felt that I could express all the feelings that I had. It took a while to experiment writing in the different languages, but for sure I can express myself in fiction only in Arabic.

AS A FEMALE EGYPTIAN WRITER, DO YOU THINK THERE IS ANYTHING THAT DIFFERENTIATES YOU FROM OTHER MALE WRITERS AND HOW YOU APPROACH FEMALE CHARACTERS?

Yes I do think in general that female writers portray female characters in a different light. I don’t think that all female writers succeed in writing about the struggles of women, but my main aim is to be objective so that the reader is never sure of whether you are a female or a male, and I think that is the main challenge. I have met a lot of people who read the novel and said that a man could have written this, and so in my opinion, the real challenge for any writer is to represent characters in a sincere way.

I do think that the problem with some male writers is that they are usually unaware of the inner struggles and conflicts that occur for women, and sometimes portray them superficially, even though a woman can in fact hold an entire novel.

For instance, the female characters in my other novels like ‘Mortal Designs’, which was translated into English, was a widow from the countryside and was the main character, and also ‘Professor Hanaa’, which won the 2009 Sawiris Foundation literary prize and got translated into several languages, looked at the struggle of an academic professor in Egypt. The struggle is not necessarily against the man, but against the overall community that created these struggles for her.

WHAT DO YOU WANT THE READER TO COME OUT WITH FROM THIS BOOK?

I want readers to understand history, and to think in a different way about historical and social issues, and how they judge and perceive others. I also want them to think deeply about the human experience, and to think from all different perspectives, and this is mainly what I want for all my novels.

Comments (2)

[…] “I wanted to specifically look more at the human side of the Mamluks and understand them as human beings, as in most history books and novels, you will see that the Mamluks are usually portrayed as the oppressors, but their own human experience of being slaves and then becoming rulers later on is never touched upon,” Bassiouney told Egyptian Streets in an exclusive interview. […]

[…] “I wanted to specifically look more at the human side of the Mamluks and understand them as human beings, as in most history books and novels, you will see that the Mamluks are usually portrayed as the oppressors, but their own human experience of being slaves and then becoming rulers later on is never touched upon,” Bassiouney told Egyptian Streets in an exclusive interview. […]