Weeks ago, Austria novelist Peter Handke was awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize for literature “for an influential work that with linguistic ingenuity has explored the periphery and the specificity of human experience.”

The news, controversial as it was, served as a reminder that the prestigious award is not that far off from Egypt.

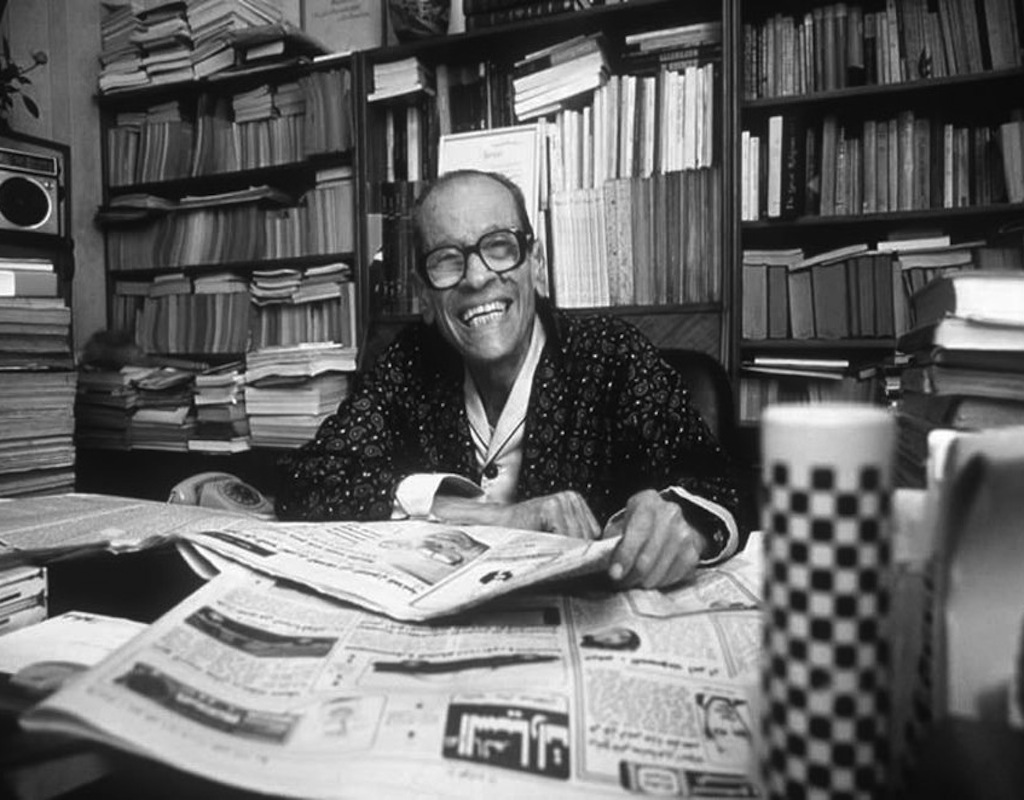

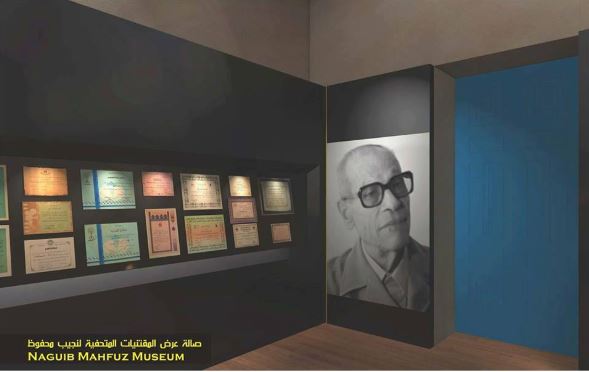

Thirty-one years ago, exactly on the 13th of October 1988, Naguib Mahfouz became the first Egyptian to win Nobel Prize in literature.

This prize came with full merit after a long journey replete with creativity and transmitted knowledge in the field of literature.

Hailed as Egypt’s iconic and most famous writer, Mahfouz’s craft has been highlighted in the last decade as his works carries the reputation of conveying the reality of Cairo’s streets. His work was influential as it also framed some of the struggles which plagued Egyptian society through time.

Several novels by Mahfouz gained popularity and achieved high success. One his most elegant and simple works, which is often overlooked, is undeniably his Nobel prize speech.

The latter was not delivered by Mahfouz himself. The great novelist had a well-known fear of flying, prompting Mohamed Salmawy, another Egyptian author, to receive the prize in his stead.

The first two paragraphs of the speech are significant for they narrate Mahfouz’s attachment to his city, culture and language. After conveying gratitude, he asserts that the prize he has won goes to the Arabic language, the real winner.

He also insisted on the speech being delivered in Arabic so that the language could make an international appearance in a very prestigious event, hopefully, not for the last time.

In his introduction, Mahfouz also expressed gratitude to the two cultures he was an enthusiast of and he considered himself the cultural son of: ancient Egyptian and Islamic cultures. “It was my fate, ladies and gentlemen, to be born in the lap of these two civilizations, and to absorb their milk, to feed on their literature and art,” his speech says.

As the speech proceeds, the novelist attempts to dissolve the negative stereotypes the two cultures seem to bear. He explains that, for the ancient Egyptians, justice was a principle. Hence, Mahfouz narrates a story found in an ancient papyrus; the infamous story tells of a sinful relation between one of the ‘harem women’ of the pharaoh and a court man.

Upon discovering the betrayal, it was expected that the king would execute both immediately but the ruler proceeded differently. The king asked to investigate the incident as he wanted to declare the truth instead of an execution.

Mahfouz considers this story an attempt at showing that truth is more valuable than conquering lands or building pyramids.

As for the Islamic civilization, there are famous achievements that history cannot deny. In fact, this civilization calls for the establishment of a union between all mankind, under the guardianship of the Creator, based on freedom, equality and forgiveness.

With this into consideration, Mahfouz narrats an incident which highlights the importance of acquiring and furthering knowledge in the Islamic culture: “In one victorious battle against Byzantium, it has given back its prisoners of war in return for a number of books of the ancient Greek heritage in philosophy, medicine and mathematics. This is a testimony of value for the human spirit in its demand for knowledge, even though the demander was a believer in God and the demanded a fruit of a pagan civilization.”

After presenting the two cultures, Mahfouz talks about what is known now today as the third world: a region described as suffering from the burden of debts and from an absence of human rights in an era obsessed with them.

Then, he asks “Yes, how did the man coming from the Third World find the peace of mind to write stories?”answering that it is arts that give man salvation and respite.

Mahfouz then ends his speech in an apologetic tone; he knows he drew a disturbing picture of the suffering third world country from which he originates.

Nonetheless, he asserts, that despite all severe circumstances he is still optimistic and confident that ‘pain’ will fade away .

Finally the closing sentence was quoted from the poet Abul-‘Alaa’ Al-Ma’ari showing that people remember the causes of pain rather than of happiness.

“A grief at the hour of death

is more than a hundred-fold

joy at the hour of birth.”

This speech reflects many of the miseries Egypt has been facing throughout history, not only during Mahfouz’s lifetime.

Generally, Mahfouz’s writings show his attachment to his native city and country. His writing conveys grave concern with societal problems; it also particularly draws literary caricatures of the citizens and the landscape of the country which serves to inspire critical thinking about Egyptian society.

Through his novels and articles, Mahfouz addressed certain issues plaguing his community – a key feature in his writing eliciting appreciation. Doubtlessly, Mahfouz is considered a figure perpetually enriching literacy in the Arab world.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article do not reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comment (1)

[…] had the chance to see these monuments has read about them and pondered over their forms,” his speech […]