Egypt has a unique and deeply rooted culinary tradition that goes back thousands of years. Sharing dishes is common courtesy; festivities are an excuse to celebrate food, and hosts don’t take no for an answer.

But food culture is not static. Years ago, for instance, the coastal city of Alexandria was known to be cosmopolitan, providing a backdrop for the mingling of Greek, Italian, French, Armenian and British culture.

Today, Egyptian cuisine is shaped by many different factors. Egyptians travel abroad and take their cooking skills to the corners of the Earth, while returning expatriates bring foreign flavours into traditional Egyptian dishes.

But what are Egyptian traditional dishes? Fuul, molokheya, and koshary – to name but a few.

Yet while each of them remains a significant part of Egyptian culture, many new culinary trends have emerged over the past decades.

David Blanks, food critic and former AUC history professor, said that even the most typical Egyptian foods are not cooked in the same way in two different households. Regional and class differences come into play, even in dishes that are popular all across Egypt.

Food in Egypt

Blanks, who now heads the history department at Arkansas Tech University, told The Caravan that changes in culinary traditions are always tied to global trends and socio-economic changes.

In recent years, many restaurants in Egyptian urban centers added home delivery to their service, a tradition which is uncommon outside of Egypt according to Blanks’ writing.

Iman Gaddoua’, long-time Cairo resident and vice-dean of the National Heart Institute, also said that the phenomenon was not at all prevalent in her youth.

“When I was in school and university in the 60s and 70s, everyone always ate at home,” Gaddoua’ told The Caravan.

In her experience, food was not only cooked and eaten at home, but many of the ingredients were grown, made and even bred there, too.

While this is still the case in rural parts of Egypt, many city residents have shed these traditions.

Gaddoua’ believes that one of the reasons eating out and ordering takeout is becoming increasingly popular in Egypt is that the social structure has changed over the years.

“Wives and mothers were expected to be at home and make the food,” Gaddoua’ said. “But nowadays every member of the family is working and too busy to cook.”

In Touch with Global Trends

Blanks also explained that, among other phenomena, regional migration has made for a larger variety in the food offered in Egypt. Syrian and Lebanese cuisine have been gaining a sure footing in Egyptian food culture for many years.

However those cuisines, like everything else that comes into Egypt, are not left unchanged.

“Everything is being Egyptianized,” said Blanks. “Even pizza is being Egyptianized. They’re catering to local style.”

While Blanks said that Egyptians by and large, even in the middle and upper classes, are often looking for traditional foods, this has not stopped them from being in touch with global trends.

Sushi is a prime example of this. A food that is very different from the culinary traditions Egyptians are used to, it still managed to find its way into elite spots some twenty years ago. Blanks said that over time, the trend began to spread among the middle class as well, “so that they become a part of the ‘in’ social group.”

But while the pricey bills at sushi restaurants often limit the variety of their clientele, other more affordable ethnic eateries such as the Uyghur Fuul El Seen El Azeem and the Sudanese Arij have also been gaining ground in Cairo.

Tucked away in less gentrified areas, they are often run by non-Egyptians bringing their own local cuisine to their new home.

Bringing Egyptian Food to the World

Egyptian restaurateurs approached the trend of ethnic eateries with a slightly different attitude: they are trying to make making local food the sought-after, hip ethnic cuisine inside Egypt itself.

“Internationally, ethnic foods became cool about 10 years ago,” Blanks told The Caravan. In cities like London, Paris and New York, food courts with ethnic eateries from around the world have become popular.

“Wealthy, westernized elite restaurateurs saw a local market,” Blanks said. “They wanted to make it cool to eat koshary. A lot of elite families would eat koshary and fuul, but they’d eat it quietly at home. It was a secret pleasure,” Blanks added.

With these new restaurants, upper and upper-middle class eaters could “pig out”, as Blanks put it, on traditional Egyptian foods – only they would do it at a trendy location.

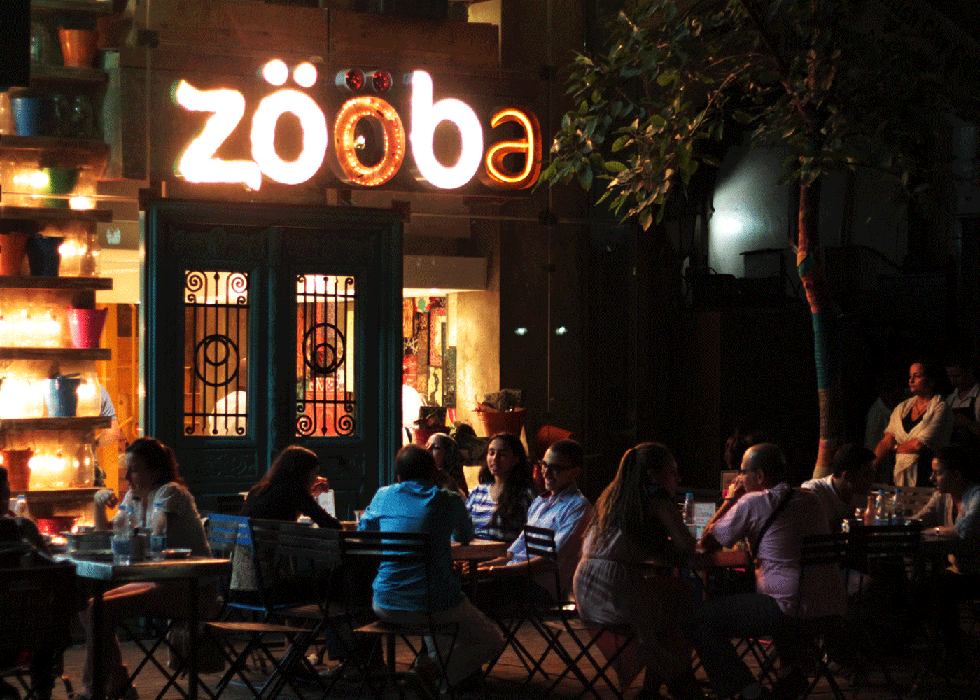

Chris Khalifa, founder of a popular Egyptian eatery named Zooba, said that the unique proposition of this restaurant lay in innovating what was already there.

“We have great street food in Egypt,” Khalifa said. “The idea behind Zooba is valuing better hygiene, and putting more emphasis on quality ingredients. No one has tried that with Egyptian food,” he added.

Street food in Egypt, like in many other societies, has long been an integral part of the daily life of millions of Egyptians, who rely on it for workday meals, rather than for indulgence.

However Khalifa told The Caravan that he does not believe that creating a brand around it takes away from its authenticity. He explained that for Zooba, street food is not about the location in which it is sold, but about the food itself.

“For us, having different options and innovation in food in general adds to the value of the food culture in the country, and adds value to the food scene in general,” Khalifa said. “The more people get creative with their national cuisine, the deeper the culture of your national cuisine becomes,” he continued.

Blanks, who is also a former restaurateur, predicted that that this trend will not be limited to Egypt; a prediction that came true when Zooba opened a branch in an upscale area of New York City.

Khalifa told The Caravan that this had indeed always been a significant part of the plan at Zooba.

“I believe very strongly that Egyptian food is exportable. There are no Egyptian restaurants lining the streets of any major city in the world, but we have a very strong food culture, a deep culture, but it really hasn’t at all been pushed past its raw form,” he said.

“It can be portrayed in the same light and with the same quality as other cuisines that are becoming very trendy. It can fit in and have its own clientele. It’s our vision of it,” Khalifa concluded.

This article was first published on The Caravan. The Caravan is the bi-lingual weekly student newspaper of the American University in Cairo, offering the community a combination of reporting and commentary on campus life, politics, popular arts and culture and the latest developments in the worlds of business, science and technology in both English and Arabic.

Comment (1)

[…] EGYPTIAN STREETS BY: AMINA […]