On Sunday the 25th of November 1923, two months after the maestro’s death, The Manchester Guardian Weekly ran a profile on Sayed Darwish, “the national hero who brought Egyptian music into the twentieth century.” Like so many other stories about this great composer it began with a tale of generosity, heavily inspiring this article.

One cold December night, a shaggy arbagy horse carriage driver entered a café in Alexandria’s Kom El-Dika neighborhood looking for al-Sheikh Sayed Darwish. According to the cafe’s owner , the man’s long brown face and manure stench made him hard to distinguish from his horse. Gripping a slaughtered unfeathered duck, the driver loudly asked to see Sheikh Sayed. Everyone in the café burst out laughing. They were all there to see the sheikh. The café, once called something else, had been renamed the Sayed Darwish Café.

In the beginning, Darwish, a local, sang there for tips. Now the old wooden chairs and sawdust covered floor were packed with fans hoping to catch a glimpse of the star, or a handshake, or even if they were lucky, a free concert.

Darwish began to sing in this cafe – where the duck event took place- in 1906-7, when he was a teenager. He was born in Kom ad-Dika and lived nearby. His father died when he was 10 and he sang there for tips to help feed his mom and sisters. As his star rose in Alexandria (he became a well known wedding singer, which is why the other carriage driver knew him) the entire neighborhood would come listen to him.

The driver didn’t recognize Darwish in a suit, only in his traditional sheikh robes. Once Darwish began working in Cairo’s theaters (1918, age 26) he quit singing in that café, moved to Cairo and wore suits more often. But he would come home to visit.

Undeterred, the driver plopped himself down in a corner to wait. After several hours without ordering even a cup of tea the owner finally asked why the man was there with a dead duck stinking up his café. The man replied the sheikh had performed for his new baby’s Sobo‘ the night before but had refused payment. As a proper Sa’idi he couldn’t accept that, so he came with a gift for the sheikh.

Darwish arrived around two in the morning and when he saw the driver went straight to him. He hugged the man and insisted he shouldn’t have brought the gift. Only after the driver swore on his mother’s grave did the sheikh accept the bird. Apparently Darwish had ridden in the man’s carriage but dressed in a suit rather than his normal religious attire and the driver hadn’t recognized him.

As they passed another carriage, the man reminded its driver not to forget his son’s sobo‘ that night. The other driver laughed at him and said, “Why is it so important? Is Sheikh Sayed performing?” This angered Sheikh Sayed, who slyly asked his driver where he lived. He later showed up at the celebration and sang for three hours straight.

“Yes, I used to work with him,” another tale began. Its narrator, like many from the Nile Valley’s rural villages, had been forced to seek work in the city when a steep drop in cotton prices took away his livelihood.

The Americans had flooded global markets after their Civil War and prices had plunged. Alexandria was suffering from the same economic plight as the rest of the country and there were few jobs to be had, so the man took a construction job.

“We used to work for the same construction crew. He just finished his religious studies and had enrolled in a music school. He worked for a while as a wedding singer but didn’t earn enough money so he started working in construction. He used to sing labour songs to encourage us to work. He really affected us. The foreman noticed that and instead of paying him to work, paid him to sing for us instead, to cheer us up. One day as we were laying bricks in Labban two Syrians stopped to talk to him because they liked his singing. Two weeks later, he bid us farewell. They took him to Syria to learn more about music. I didn’t see him for some time after that, four years I think, and then I heard him singing in this café.”

The two “Syrians” were the Alexandria-born Lebanese Amin and Selim Atallah, two famous Egyptian artists who in 1909 hired Darwish to go on tour with them to the Levant. There he learned the basics of Middle Eastern and modern European music and blended it with Egyptian folk songs to create an unusual new style.

When he returned home he failed to impress Alexandrian audiences, however. A year later he went back and learned more, and this time when he returned his new music caught the attention of artistic circles – but not the general public. The most influential of these artists was Salama Hegazi, another legendary singing Sheikh, who heard Darwish play in Alexandria and invited him to perform at his Cairo theater during intermission. And so, it came about that Sayed’s name began to circulate in Cairo’s theatrical world.

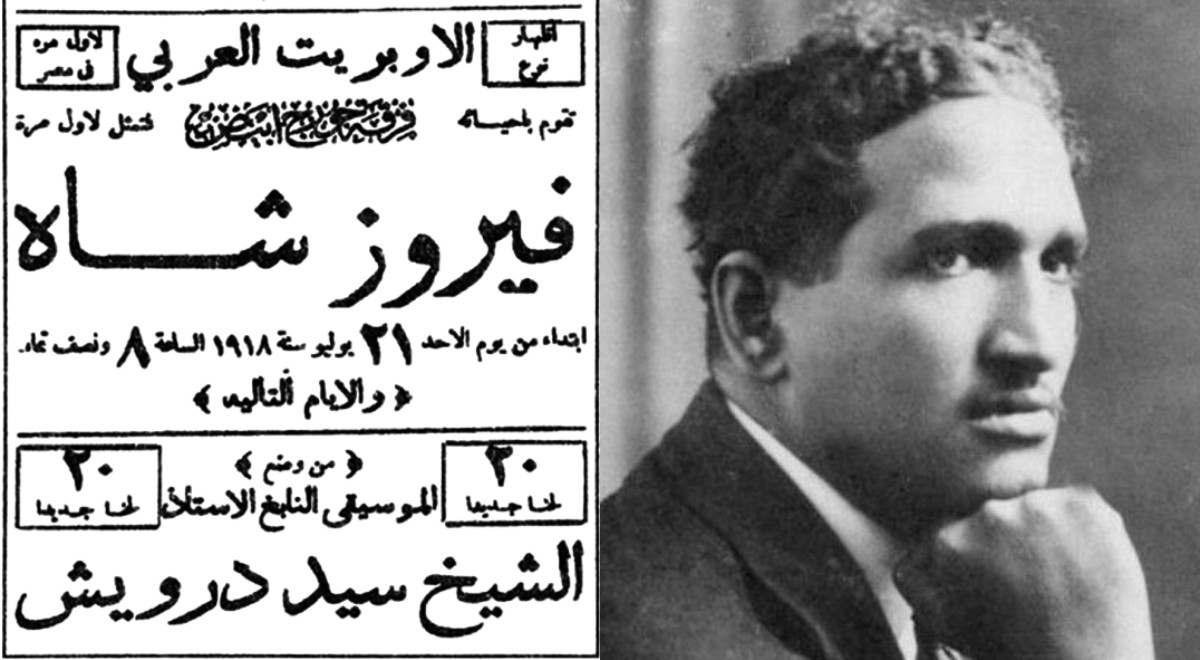

The Guardian reporter also interviewed Sayed Darwish’s closest collaborators, Badia Khayri and Naguib Al-Rihani, who transformed early Egyptian theatre in the same way that Darwish transformed Egyptian music. Before them Egypt was considered a stagnant backwater for European plays and operas. However, during World War I Al-Rihani invented the comic character Kish Kish Bey whose success enabled him to start his own theater troupe in 1917. Among his first hires was Badia Khayri, one of Egypt’s first playwrights. After Sayed Darwish joined the duo the following year, his plays almost always included musical numbers by Darwish. The two collaborated outside the theatre as well, but it was their theatrical success that propelled Sayed to stardom.

According to Al-Rihani even their first collaboration was a hit. “The play opened from here, and people’s wallets opened from the other side. You couldn’t walk anywhere without hearing one of the play’s songs, Al-Helwa Di Amet Te’gen. But the real fascination here was that me, with this same voice you hear now, this harsh deep voice of a man that before only sang as a joke, he wrote me a song that, when I performed it on stage, captivated audiences to the point where they broke their fingers clapping. I think all the famous singers in our opening night audience felt threatened by my singing because of him.”

The 1919 Egyptian Revolution the following year that established Darwish as a superstar. According to Badia Khayri, “The People’s Artist” collaborated on over 70 patriotic songs that year alone and continued to compose more until Egypt was liberated from Britain four years later. Thus the maestro’s fate came to be intertwined with that of Sa’ad Zaghloul, the former member of The Egyptian Legislative Assembly who led his country’s delegation at the Paris Peace Conference after World War I. Zaghloul petitioned for Egypt’s independence from the British but was exiled to Malta for his efforts – until the 1919 civil unrest forced his reprieve. But negotiations broke down and Zaghloul was returned to exile, this time in The Seychelles. A compromise was finally reached in 1923 and Zaghloul once again set sail back to Egypt.

To commemorate the occasion Darwish wrote Bilady Bilady (Egypt’s national anthem) which was to be sung at the grand celebration planned in Alexandria for his arrival. Tragically, he passed away days before Zaghloul’s boat docked under suspicious circumstances. He was thirty-one years old.

March 17, 2021 marks his 129th birthday.

Sources to read more:

Al-Masry Al-Youm, Naguib el-Rihani’s memoirs. October 29, 2015,

Ameba, Safa. Mohamed Sayyed Darwish to Majalla: My Grandfather Was Poisoned By the British Occupational Forces. How Sayyed Darwish Grew from Azharite to Revolutionary Icon. Majalla, Cairo. 17 January, 2020

Fathalla, Isis, Darwish, Hassan and Kamel, Mahmoud. Sayed Darwish – The Encyclopedia of Arabic Music Figures. Cairo, Dar Al-Shorouk

Gharib, Ashraf. Remembering musical pioneer Sayed Darwish. Al-Ahram, Cairo. Friday 20 Sep 2019.

Lagrange, Frédéric. Shaykh Sayed Darwish [1892-1923] : Artistes Arabes Associés AAA 096 Les Archives de la Musique Arabe – Shaykh Sayed Darwish. October 1994.

Noshokaty, Amira. Said Darwish: In the service of music. Al-Ahram, Cairo.

Slight, John. The Egyptian Revolution.

Saudi 24 Hour News. Ya Balah Zaghloul: Beyond the bounds of logic … the song “Ya Balah Zaghloul” was banned from a theatrical performance in Egypt.

The Alexandrian Minister of Culture, Sayed Darwish: Fanaan as-Sha3b. Alexandria. 1962.

The Manchester Guardian Weekly, The man who transformed Egyptian music: Sayed Darwish. 25 Nov, 1923.

Comments (4)

[…] Celebrating Egypt’s Prominent Musician: Sayed El Darwish Brands with a Nostalgic Touch: Growing Egyptian Brands that Connect and Inspire […]

[…] العشرين”، على حد وصف الملف الكامل الذي نشرته صحيفة The Manchester Guardian Weekly عن مشواره الفني يوم الأحد 25 نوفمبر 1923، أي بعد شهرين من […]