Bread has a long and arduous history of being the trigger for uprisings and revolutions across the globe. It has been featured in most slogans of revolutions in the last few centuries, some of them transnational, having spread across imaginary borders.

In Egypt, when we think of bread, it is usually in reference to one of two related elements: subsidies and the 25 January Revolution of 2011. The most recent and vivid memory of bread and revolt is tied to its featuring in Egypt as part of the 25 of January revolution slogan: “eish, horeya, a’dala egtema’eya” (bread, freedom, and social justice), but in another January years before, there was an uprising that was dubbed “Intifadet Al-Khobz” (The Bread Intifada, or Riots) in 1977 that has been lost to history.

مش كفاية لبسنا خيش…جايين ياخدوا رغيف العيش

(It’s not enough for us to wear burlap… they are coming to take our loaf of bread)

This was one of the main slogans of the Intifada, but the one that is more easily recognizable nowadays is: “Sayed Marei, Sayed Beih (sir), a kilo of a meat now costs a geneih (Egyptian Pound).”

Egypt’s Lost Uprising

According to Al-Ahram, on 17 January, 1977 Deputy Prime Minister for Economic Affairs Abdel-Moneim Al-Qaisouny stood in Parliament to state a few of President Anwar Al-Sadat’s decisions for the new year. One of the decisions Al-Qaisouny stated was enacting a form of austerity the President deemed necessary, cutting EGP 500 million from the country’s budget by canceling subsidies of over 25 basic products including bread, cooking oil, sugar, and tea.

In “ Popular Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East”, historian John Chalcraft dedicates a chapter to the Egyptian Leftist movement and its return to the political arena post-1968. Chalcraft writes that there was a 50 percent cut in subsidies for necessary foodstuffs and gas. Which means that the loaf of bread that used to cost one ta’reefa became one qirsh instead. A ta’reefa is five milliemes and a qirsh is 10 milliemes, 1 EGP is 1000 milliemes. This means that there was a 100 percent increase in the price of bread. It has also been said that the one kilogram of meat increased to cost EGP 1 when it was 60 qirsh before.

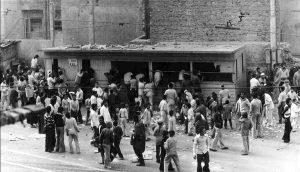

On 18 January, the morning after the news broke, thousands of people took to the streets inside and outside of Cairo.

There were no peaceful protests as people’s livelihoods were forcefully taken away and what little support they had from the government in terms of subsidies was canceled without prior notice.

According to Chalcraft, the first group who took action on the fateful morning of the 18th were the workers of the Misr Spinning and Weaving Company of Helwan. They marched around the industrial area, chanting their demands, which included canceling the cut in subsidies. Following them were the students of Ain Shams University, who marched and protested in downtown Cairo, attracting a large number of people who were shocked and then outraged at the increase in prices.

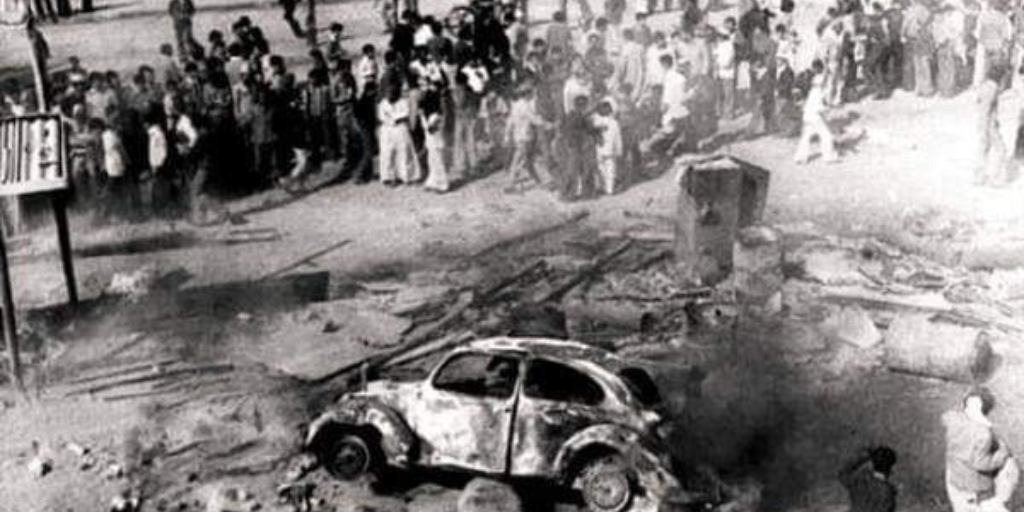

The protestors burned the police stations of Al-Azbakeya, Al-Sayyeda Zeinab, Al-Darb Al-Ahmar, Imbaba, and even Cairo’s Directory of Security. The violent resistance of the rioting population was nation-wide, from Al-Arish to Al-Salloum and Alexandria to Aswan. The riots were destructive, and they were everywhere. Being an industrial area, Shubra Al-Khayma especially was completely occupied by workers.

Rioting masses also camped in front of the houses of most governors and threatened to burn them down. Others took to the streets, burning parked private cars. University students, workers, government employees, activists, lawyers, authors, and artists were all involved on ground, protesting, rallying, and yelling various slogans:

مش كفاية لبسنا خيش…جايين ياخدوا رغيف العيش

(It’s not enough for us to wear burlap… they are coming to take our loaf of bread)

يا حاكمنا في عابدين…فين الحق وفين الدين؟

(Oh, our ruler in Abdeen… where is the truth and where is the deen (religion)?)

سيد مرعي يا سيد بيه…كيلو اللحمة بقى بجنيه

(Sayed Marei, Sayed Beih (sir), a kilo of a meat now costs a geneih (Egyptian Pound))

يا حرامية الانفتاح الشعب جعان مش مرتاح

(O thieves of the infitah (Open Door Economic Policy), the people are hungry and uncomfortable)

احنا الطلبة مع العمال ضد تحالف رأس المال

(We, the students with the workers, are against the capitalist alliance)

هو بيلبس آخر موضة واحنا بنسكن عشرة في أوضة

(He wears the latest fashion, and we live ten in a room)

يا ساكنين القصور الفقرا عايشين في قبور

(O dwellers of palaces, the poor are living in graves)

The third slogan is more recognizable because Sayed Marei was the Minister of Agriculture and Land Reclamation during the presidency of Gamal Abdel Nasser. He was one of Egypt’s richest men in the Sadat era.

The historical context

Economically, two factors were important to consider for context; the involvement of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank and Sadat’s 1975 Open Door Policy.

Neoliberalism first emerged in the 1930s as one of the results of the World Wars; the IMF and the World Bank developed a recipe that they claimed would help develop any country. By the 1970s, they were enforcing the neoliberal recipe in exchange for loans. The recipe’s first ingredient is fiscal austerity, which is a set of strict economic policies enforced by a government to exert damage control on a country’s growing public debt.

President Sadat wanted to ensure that Egypt could receive yet another loan from the IMF with the backing of the World Bank. Besides the fact that austerity itself is a controversial factor in the neoliberal recipe and has been known to have detrimental effects if not properly managed on a national level, Sadat insisted on the loan. To this day Egypt continues receiving loans from the IMF.

It is important to note that austerity was not the only ‘major’ decision Sadat took to enforce neoliberal policies.

Three years earlier, in 1974, President Anwar El-Sadat enforced Al-Infitah, or an ODEP (Open Door Economic Policy). Al-Infitah was an economic program that was based on liberalization, officially marking the departure from his predecessor Gamal Abdel-Nasser’s more socialist and nationalist policies.

Essentially, the aim was to revitalize the private sector and introduce capitalism more heavily, allowing for the country’s ‘doors’ to open to foreign and Arab capital, thereby dismantling a large chunk of the public sector.

These changes began to move Egypt’s general economic policies towards a more “laissez-faire, laissez-passer” capitalist mentality. “Laissez-faire, laissez-passer” translates to “let be and let pass” but it is also used to refer to a capitalist economic policy that encourages a lack of interference by governments in private business. The decision to enforce the ODEP was one with major repercussions which the working class and the poor felt the brunt of.

President Sadat ordered the Central Security Forces to the streets armed with tear-gas to block streets across the country, and, noting failure, he ordered the army to go in as back-up, fully armed. Casualties were high and a state of emergency was enforced by the state and the army with a strict curfew, from 6 P.M. to 6 A.M., yet the Intifada continued, undeterred.

However, on that day, three major newspapers and the national TV published a statement by President Al-Sadat stating that the government was aware of a secret communist organization aiming to cause instability in the country and to eventually overthrow the government.

According to revolutionary poet Zain Alabidin Fouad, dozens of students, artists, workers, and activists were forcefully detained during that day. Some of those detained in the case of the January 1977 riots; Ahmed Fouad Negm, Hussein Abdel-Razek, Salah Eissa, Amir Salem, Zain Alabidin Fouad himself, and others. Their lead defense lawyer was Essam Al-Islambouly. The accused in this case were divided between Torah, Abu-Zaabal, and Al-Qalaa prisons.

It was actually in this particular stint in prison that Leftist revolutionary and poet Zain Alabidin Fouad wrote his famous poem “اتجمّعوا العشاق”:

“اتجمعوا العشاق في سجن القلعة

اتجمعوا العشاق في باب الخلق

والشمس غنوة من الزنازين طالعة

ومصر غنوة مفرعة في الحلق

اتجمعوا العشاق بالزنزانة

مهما يطول السجن، مهما القهر

مهما يزيد الفُجر بالسجانة

مين اللي يقدر ساعة يحبس مصر”

“The lovers were united in Al-Qalaa prison

The lovers were united at Bab Al-Khalq

And the sun is a song rising from the cells

And Egypt is the singular song ringing in the throat

The lovers were united in the cell

No matter how long the detainment, no matter the oppression

No matter the cruelty of the guards

Who can imprison Egypt for even an hour?”

This poem was one of the first Fouad wrote and he waited until they (himself and the other activists in the case of inciting the riots of 18 and 19 January) were presented in Bab Al-Khalq for their appeals and smuggled it out to the revolutionary singer and composer Sheikh Imam, who sang it to rally the people.

The protests continued until 19 January, when President Sadat appeared live on national television announcing the cancellation of his earlier decision to enforce austerity by removing subsidies on basic necessities.

For some, the Intifada was the climax of the various riots the working class and the Egyptian Left led between 1968 and 1976, others say it was a swift reaction to the neoliberal economic policies enforced by the regime.

President Anwar Al-Sadat called what is known to the people as ‘Intifadet Al-Khobz’ (The Bread Riots), ‘Intifadet Al-Harameya’ (The Uprising of Thieves).

Comments (21)

[…] بعد 45 عاما: إحياء ذكرى انتفاضة الخبز المصري […]

[…] بعد 45 عاما: إحياء ذكرى انتفاضة الخبز المصري […]