Public outcry, controversy and outright mockery on the state of Egyptian street sculpture. From the ugly bust of Queen Nefertiti to an unexpressive, unimaginative replica of Nahdet Misr by Mahmoud Mukhtar, public opinion has become increasingly frustrated with the state of contemporary street sculpture.

“This is an insult to Nefertiti and to every Egyptian,” tweeted one Egyptian woman. Another wrote: “It should be named ‘ugly tasteless artless statue’… not Nefertiti.”

However, over the years the modern art movement in Egypt has had unnoticed moments of genius, triumph and innovation that have helped influence sculpture as a modern art form.

This is the untold story of contemporary Egyptian sculpture.

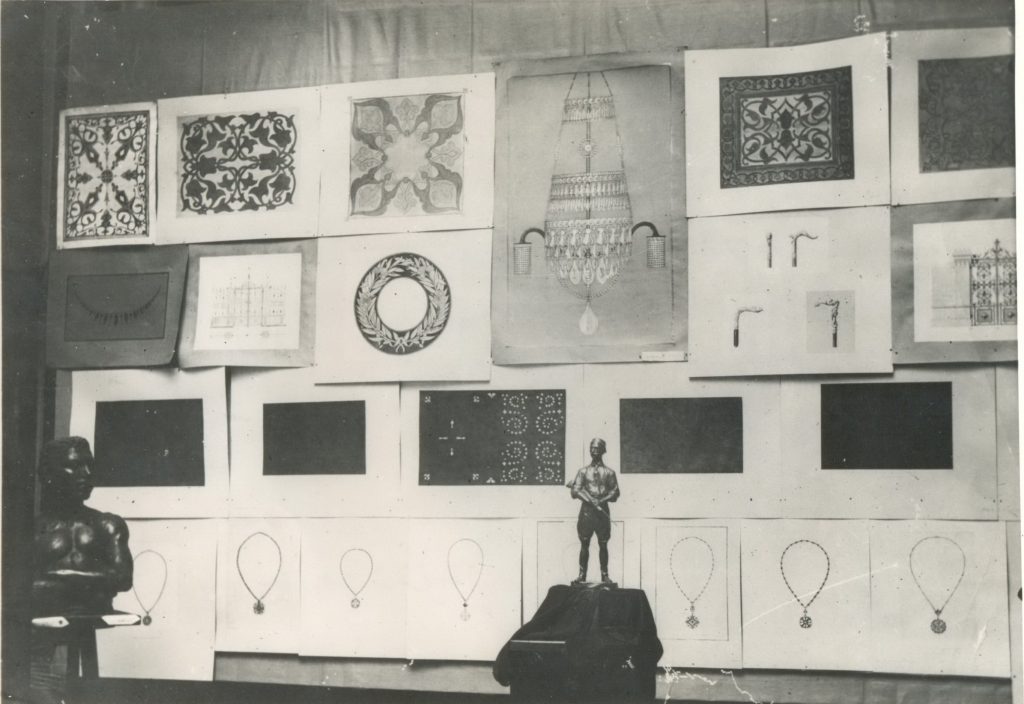

A nation on the brink of modernity and cultural upheaval, Egypt in the early 20th century was undergoing rapid socio-cultural change in the face of foreign occupation. It was 1912 when the first graduating class of the School of Fine Arts in Cairo erupted onto the artistic scene with a blend of renewed recognition for national patrimony, revolution, and a return to the ‘classical’ art traditions of ancient Egypt.

These pioneering contemporary artists and sculptors, al-Ruwaad (the pioneers), would lay the foundations for Egypt’s modern art movement. An immediate and defining form of visual expression, the art of sculpture would come to symbolise this era of burgeoning creativity.

Perhaps there is no sculpture more emblematic or illustrative of this era than Nahdet Misr (Egypt Awakened or Egypt’s Renaissance), erected in 1929 by Mahmoud Mukhtar (1891-1934), who is considered the father of modern Egyptian art and sculpture.

Mukhtar’s masterpiece was a sublime interpretation of national identity in a neo-pharaonic style that would come to define this blossoming age for Egyptian art. Elina Sairanen, a leading scholar of pan-Arab art collections and museums, recalls that “this movement combined the country’s ancient artistic traditions with contemporary techniques and teachings, reshaping them to a visual language that reflected a distinct Egyptian individuality”.

However, the second and third generations of contemporary sculptors would challenge notions of nationalism and ancient artistic tradition. No longer was the art of sculpture defined solely by the socio-cultural, economic, or political climate in Egypt.

Sculptors began to experiment with subjects and themes dominated by the surrounding natural environment. Art and sculpture began to delve deeper into the unconscious mind, and deeper into abstraction and minimalism. The focus had shifted from nationalism, politics and tradition, to a study of the self and the artist within.

Mohammed Abla, a renowned visual artist and sculptor, has been at the forefront of these thematic changes. Abla believes that Egyptian sculpture is dominated by conformity; a repetition of topical themes and subjects have, in his opinion, rendered sculptures uniform, bland, and hollow.

“It tends to represent specific direct ideas, rather than reflecting the identity of the sculptor. This makes most of the sculptures look so alike” he argues. One of his masterpieces, Sisyphus (1992), perfectly exemplifies his experimentation with self-reflective and minimalistic styles.

However, Abla’s contributions to modern Egyptian sculpture are not limited to thematic changes alone. He was quick to identify the changing role and impact of sculpture in contemporary Egyptian society. Abla realised that “there are no more street sculptures today…this culture is almost absent in our current society”.

Abla highlights the fact that Egyptian society has become less attentive and accepting to sculptures in public areas.

Another artist, Tarek Al-Koumi, is known for his sculptures of singers Umm Kalthum and Mohammed Abdel-Wahab standing at the Cairo Opera House. He believes that “street sculptures have always had a symbolic significance and are linked to the notion of visual culture. Unfortunately, a minority has this culture. And it is obvious that in such an atmosphere it is ugliness that reigns.”

Nonetheless, contemporary sculptors are adapting this art form in novel ways to ensure its continuance as an effective and representative communication tool. Artists like Naguib Moein and Nevine Farghaly, continue to push the boundaries of sculpture by altering forms, subjects and materials used.

Nevine Farghaly produces “small works that include tens of intricate pieces … she focuses on producing sculptures that include figures and animals as well as sculptures with mechanical movement.” Her unique incorporation of metal and movement, as well as various sizes, aims to increase public appreciation, associability and accessibility to contemporary sculpture.

An impactful form of artistic expression that has proven vital to the bustle of urban life; sculpture continues to play an important role in public spaces and in homes across Egypt. Continuity, innovation and tradition have coalesced to influence generations of Egyptian sculptors, and impact Egyptian society.

The history of Egyptian sculpture has been shaped by its ability to confer emotion and thought: An ever-changing, and dynamic kaleidoscope of emotion and thought.

Comments (2)

[…] دمج التقليد والتجريد: النحت المصرى المعاصر […]

[…] دمج التقليد والتجريد: النحت المصرى المعاصر […]