I was 18 when I legally applied to change my name in court, in the Netherlands.

I was born ‘Somayah’ daughter of a Dutch mother and an Egyptian father. They divorced when I was very young. I don’t remember much from the time they were together, apart from two fights that occurred in the Netherlands, and that one time I got stuck in an elevator in Alexandria because I couldn’t reach the buttons. I must have suppressed everything else.

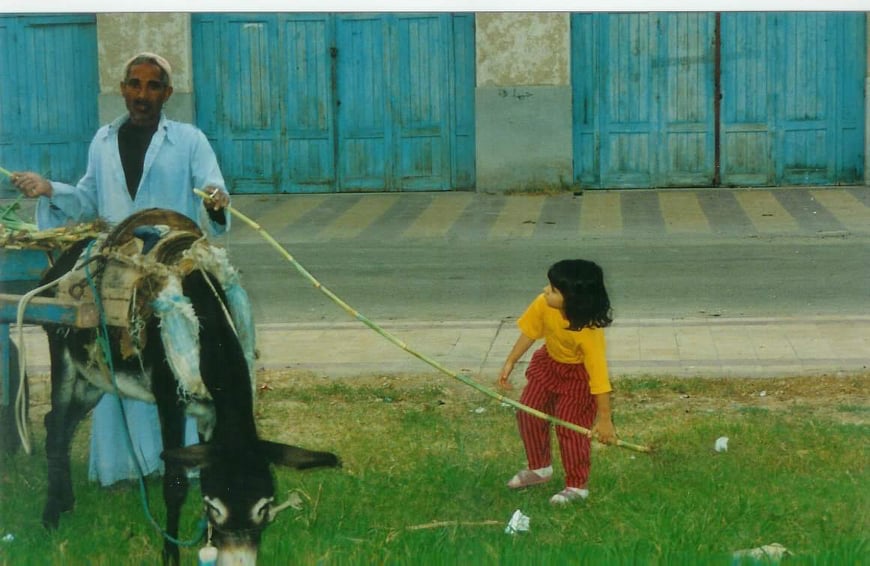

I do, however, have some vivid memories of going to Egypt when I was five or six years old. My mother would play Dutch music at my grandmother’s house in Ismailia, and my grandmother always made too much food, and bred pigeons on her own balcony. I recall her giving me some money to buy yogurt or rice pudding, which I loved, from a street vendor.

We’d also visit my dreadful aunt who made me sit on her lap and slapped my cheeks. I remember singing songs with my cousins, and standing on the hood of a stranger’s car, speaking Arabic while explaining Dutch games to kids in the neighborhood. I remember the call to prayer in the morning, the sunshine through the windows, the noise, the dust, the first supermarket that opened, the cassette stores, the mosquitos…

The last time I visited was 18 years ago; I promised that aunt that I would come back and learn Arabic. I never did, and she passed away several years ago.

I never understood that my upbringing was different. I also never saw the massive cultural and religious clash that went on between my parents. They came from distinctly different worlds, upbringing, religion, and mindset.

My life was my only point of reference, and it was normal to me since I didn’t know any better. It’s the same as when you don’t ‘see’ race until you understand what racism is. Plus, as far as I knew, I was just Dutch. Before the divorce, I may have gotten instilled with both Dutch and Egyptian values, but after my father left, Egypt left with him. And, as I grew more and more estranged from him over the years, I cared less and less about that part of me.

Surhuisterveen, the town where I grew up, is a small, Frisian town in the north of the Netherlands. There, I definitely stood out. Children would always ask if I was adopted. My name was the butt of the joke: Somayonaise, Somini, Somalia – I hated my name. In their eyes, I also had a “funny-looking nose,” and “hairy arms.”

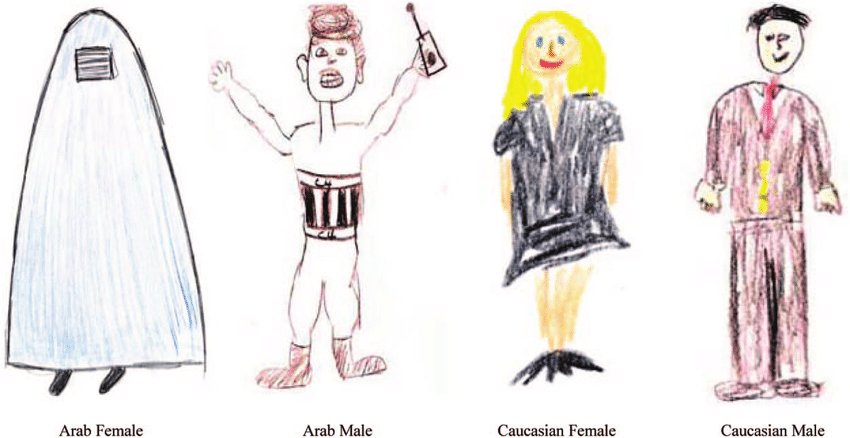

Suddenly, after 9/11, I was called “Muslim,” “Bin Laden’s daughter,” or “Arab.”

I was also called a hairy monkey, filthy Turk or Moroccan; terrorism was my “people’s fault,” and my last name sounded like “a suicide bomber…” On a more positive note, strangers would comment on the thickness of my hair, and how different it was from Dutch hair, or the “mystery” that was my race. My identity was always challenged by others. Accordingly, I persistently felt different, and confused.

Growing up, all I wanted was to reach a feeling of belonging. I didn’t want to be different. People need a sense of belonging to feel like they’re part of something bigger, and cultural identity is a powerful aspect. Trevor Noah, in his book Born A Crime (2016), described it perfectly when he wrote “I saw myself as the people around me, and the people around me were black.”

In my case, the people around me were white. But, when no one looks like you, you’re going to be perceived as different. And, growing up in a small town in the Netherlands in the 90s, there wasn’t much cultural blending occurring. There still isn’t.

On top of that, I didn’t have a father figure, and no one to actively teach me about the other 50 percent of my racial background. I was too naïve to understand then, but I understand now how much that influenced me. It was a massive internal struggle, perpetuated by the outside world, which I tried to fight as I attempted to fit in and be normal until I gave up trying.

Nowadays, this struggle is described as having a ‘floating’ identity. So I became an outcast, which never really changed. Finding like-minded friends within an alternative subculture might have been the first time I felt like I was part of something. My high school years were filled with boyfriend drama, feuds, rebellion, puberty problems, but also music, performing, and artistic self-expression; it was the first time where part of me felt like I was accepted for just being me.

Camouflaging my Egyptian self

At 18, I had developed such strong resentment towards anything Arab, that I decided to change my name. I was also told that I’d have a higher chance of finding a job with a Dutch name.

The events of 9/11, and the immigration crisis in Europe had left a deep negative image of several minority groups, in particular those from the Middle-East.

According to conservative groups, minorities were stealing jobs, occupying precious real-estate, and instilling their culture into a European one. Islam was negatively associated with terrorism, and headscarves were a disgrace. A lot of increased discrimination and racism took place while I was growing up. Unfortunately, I was negatively influenced by it as well, and it diluted my desire for association.

At that time, my foreign name was an obstacle in the construction of my identity: the name Somayah changed into a name nobody in the Netherlands would even blink twice over.

My father, whom I had been seeing periodically from my teenage years, was furious following this decision. Our relationship was already hanging by a thread, but the change made it far worse. I didn’t see him for several years after that. Without a thought, I had caved into my desire to eradicate the name; for, in my head, he was a bad person, his culture was bad, and Egypt was bad. There was a lot of hidden resentment which had blinded me to his point of view and desire to teach me about Islam and the importance of family names in Egypt.

Two years after changing my name, I left my home town to go to Leiden, for university studies. I distanced myself from Egypt in its entirety. Even when I hid my origins, I would continue to hear Arabic slurs, terrorism jokes, and questions about Islam.

Media portrayal of the Arab world is overwhelmingly negative, perpetually being associated with aggression, violence, and xenophobic behavior. Yet, I retained memories of the rice pudding, my aunt slapping my cheek, or the lullaby my father used to sing to me, Yalla Tnam Rima. I started feeling shame, laced with an incapacity to speak up and highlight that Egypt wasn’t like its Western portrayal.

A point of gradual return

By my mid-twenties, I started to put the pieces of the identity puzzle together through self-awareness. Every act, behavior, or rising feelings of anxiety have stemmed from a source. I also started to regret not trying to understand my Egyptian side. Unlike thousands who flocked to Cairo to learn the culture and language, I had never bothered to learn Arabic, Egyptian history, or the customs. My ignorance extended to Islam as well. Knowing the link between my past and current self has helped me find a world of acceptance around my ‘floating’ identity.

By the time I realized change was needed, there was a concurrent realization that there were 20 years to catch up on without an idea on how or where to start. I started with myself and went into therapy, I took on every opportunity to push myself out of my comfort zone, and focused on overcoming personal insecurities. I also started taking Arabic lessons (currently at level toddler), reading books on contemporary Egypt, and modern history, following Egyptian media and related social media accounts. I have since made new friends with similar backgrounds and experiences.

Gradually, I gained the self-confidence to attempt rediscovering what was lost.

At the age of 30, I finally moved to Egypt, after an absence of 18 years. There was a drive in me to challenge notions on the identities that were given to me, and to eventually return to the Netherlands without the shame or fear of that part of me.

I have lived in Cairo for over a year now, and I still have a lot to discover.

It’s been an intense struggle, quite overwhelming, extremely confrontational, but also incredibly beautiful. Going from not knowing one single Egyptian to suddenly being surrounded by only Egyptians was surreal in the beginning. There is an entire community of biracial Egyptians in Cairo, which was humbling; it was eye-opening to learn that I wasn’t that different.

However, having to deal with two cultures remains a double-edged sword. In the Netherlands, due to other people’s perceptions, I never felt Dutch enough. Here in Egypt, I am mostly distinctly seen as foreign. It’s sometimes almost as if my childhood is repeating itself, albeit with an increased sense of self-awareness.

Most of the time I feel at home in Egypt, and being part of a minority in Egypt creates a feeling of community. Yet, when everyone around me speaks Arabic as if I’m part of it, or laughs at my attempts to speak the language because it sounds ‘cute’ or ‘funny,’ I still feel left out. Nothing said is ever done with malicious intent, but it always touches upon my lack of identity or belonging.

Although I may never belong to any group specifically, embracing both Dutch culture and Egyptian culture as my own has created a sense of peace and acceptance. Knowing that I have full access to engage in the missing part of me and embrace both cultures as my own, has significantly improved my seemingly never ending search for acceptance and belonging.

I am half Dutch, half Egyptian, and I am proud to be biracial.

Any opinions and viewpoints expressed in this article are exclusively those of the author. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comments (3)

[…] الرأي l ثنائية العرق في مصر: أزمة هوية لا تنتهي […]

[…] الرأي l ثنائية العرق في مصر: أزمة هوية لا تنتهي […]