The arrival of the daguerrotype in Egypt, not even a year after its invention in the 19th century, enabled a great dawn of preservation. For centuries to come, Egyptians and foreigners alike would keep Egypt, and its socio-cultural and political development, forever etched in negative films.

With the arrival of the roll-film at the turn of the century, fancy British socialites, among other European travelers, would capture their hike of the pyramids, or other momentous occasions, in negatives. Alternatively, they would slap their photographs on postcards, to send to relatives back in Europe or the USA documenting their ‘exotic’ travels.

Indeed, the camera was handled by ostentatious hands – including of artists and writers alike. For the most part, their work was carried out in the cities, with shots of Cairo and Alexandria as key attraction cities for the seasoned elites.

Upper Egypt, on the other hand, remained at the mercy of painters and illustrators, much too enthused by archaeological monuments and tombs to give the Upper Egyptians, their infrastructure, customs and garb, the time of day. As such, cameras and photography became supplements to Othering formerly colonized spaces, much less concerned with nuances of culture and peoples. A famed early photographer of Egypt was non-other than Romanticism-inspired Frenchman Maxim Du Camp, notorious for his shots of Upper Egypt, namely of temples and statues, without the inclusion of locals.

Accordingly, Upper Egypt was, and still sometimes is, a far-away and subject of poetic, impressionistic imagination.

Agitated by the focus that Lower Egypt has maintained over the year, and by the selective bias and negative portrayal of Upper Egyptians by media, power-couple Faten Abu Bakr and Mahmoud Ahmed have been seeking not only to capture familiar faces of the everyday Upper Egyptian but also bring these faces home, through photography exhibits. More importantly, they have endeavored to bring their subjects to see themselves in photographs.

In a little exhibit space tucked near the domineering Colossi of Memnon, Abu Bakr and Ahmed have printed the faces of the individuals they have spent time and effort capturing, on leather hide and set them up on the Luxor Art Gallery walls.

Only weeks prior, at the opening, had an aggregation of villagers, Upper Egyptians, Luxor-locals, and travelers come to peer at their own faces, as well as the faces of their friends and family adorned on the exhibit wall.

“We wanted to get the Upper Egyptians themselves – the ones we took photos of- to see our work and see that we are doing something real. Most of these people don’t have social media to understand who we are and what our work consists of, so we had to do something to get them to know us,” explains Abu Bakr.

It had marked a first for them in the southern territory, but not a first overall.

“We’ve already exhibited a few times, but they were always traditional exhibits where we print photos and put them up in the galleries. The audience that came was always a highly educated and cultured one, photographers or photography enthusiasts, so academically, they know the importance of the topics we address in our photographs,” she continues, bemused at the cliché archetype of exhibit visitor.

According to a 2004 MET essay by Malcon Daniel, the tradition of curating ‘elegant’ photography in Egypt to a distinct audience, namely in Paris or London, had originated with Du Camp, Félix Teynard, Louis de Clercq among others. The tradition, nonetheless, had percolated until modern times.

Social cohesion and ‘anthropology of a picture’

In a previous article with Egyptian Streets, Abu Baker and Ahmed highlighted the importance of representing Upper Egypt as a dynamic and rich part of Egypt, with its own culture, and tradition, in a bid to shear negative stereotypes stemming from television series and films.

“I started paying attention to Upper Egypt’s portrayal in television about ten years ago, and I noticed that it was all very mistaken, something like the accents, which should be relayed through time correctly, is nowhere close to what I hear on a daily basis: people don’t talk like this, and I’ve been living here for a year and a half.”

Additionally, the project and exhibition’s aim is to liase the country’s varying social groups. In a hypothetical scenario, not unlike what naturally transposes in Upper Egypt: a photography enthusiast, tourist to Luxor, an archaeologist from Spain and a Qena-born subject of one of the photos would finally be able to convene and connect in one space, and reflect over the sheer depth of Egyptian culture.

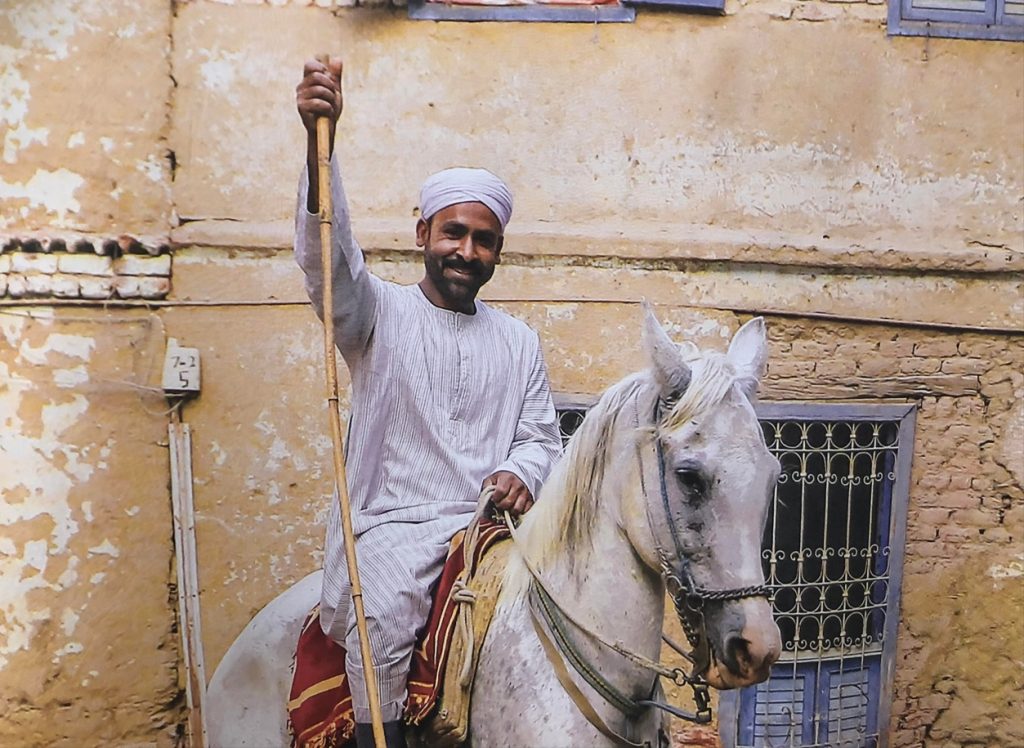

“The deepening of the connection would happen when someone from Aswan would see a photo of another from Esna whom he would be able to recognizes from his jalabeya or headdress,” explains Ahmed, who stresses identification of Upper Egyptian subcultures through garb.

He adds that, “also, the street exposition [of the portraits] would deepen that connection as people see one another. We are creating an anthropology with the photographs.”

An ephemerally tumultuous project

In the height of the 2011 revolution, transmuting into the 2013 political developments, a phobia developed in Egypt whereby the camera – and the photo it snapped – became a communal social enemy. Egyptians, plagued by the political and economic aftermath of the upheavals, lamented a haggard picture of Egypt not only transposed to the remainder of the Middle East but also to the rest of the world.

Images of destruction, poverty, and suffering were particularly worrisome, and Egypt’s government slowly enabled a crackdown on photographers and photojournalists that saw Mohammed Shawkan land five years in jail for his coverage of the dispersal of Al Rabaa El Adawiya mosque as well as clashes between protesters and security forces in 2013.

Much to the surprise of many, it is not foreigners behind a camera that Egyptians fear, but Egyptian photographers themselves.

“Being an Egyptian taking the photograph makes the situation harder,” laments Abu Bakr.

“We have the foreigner complex, and Egyptians are more willing to pose for foreigners. If he or she [a subject] sees that you’re Egyptian, they will ask you a variety of questions before you can even take the photograph: who are you? Why are you photographing me? What are you doing with these after? Why are you taking a shot of me on the farm? What if someone sees me? Are you trying to make us look bad so that people think we’re poor? But if it’s a foreigner [taking the shot], they will take their shot and leave.”

The couple admits that they have a repertoire of photographs they have accumulated through their photography trek in Upper Egyptian cities and villages that they have vowed never to post on social media or exhibit to their subjects. They nonetheless find a silver lining: individuals with whom who have formed a bond gradually warm to them and to the idea of portraiture.

“Upper Egyptians are aware of the importance of a photographer, and that the photograph has a meaning and an audience. They are a very aware segment of society that understands the implications,” explains Ahmed.

Indeed, the political implications are not the only justification behind the fear of the camera. Much like for the 19th century Malagsy people of Madagascar, some of which who were noted to have harbored a phobia of the camera as a tool of foreign etic interference, certain fears surrounding photography are more spiritual in nature.

“For the Upper Egyptians, the photo was to be refused: they used to believe that there was a ghost in the camera who would suck the person’s soul shortly after the photograph was taken,” clarifies Ahmed.

“The camera was a foreign object with flashing lights, in the past. It was scary for a lot of people. Moreover, the association with magic is strong: they [Upper Egyptians] are actually afraid of the photograph being used for witchcraft – my own sister doesn’t let me post photographs of her children online; she’s afraid that someone could take them and cast a spell,” he explains while underscoring that these are beliefs and reservations that are to be respected.

Bringing it home

In the prizewinning The Pencil of the Sun (1975) photobook, by 21st century Japanese photographer Shomatsu Tomei, the role of the photographer is defined distinctly: far from the curing of the doctor or the support of a priest, a photographer’s relentless job is to look.

“That is why photographers must continue to look things through and through. Photographers should gaze at their subjects head on, their whole form becoming an eye as they face the world. To stake their everything on looking, that is to be a photographer.”

Photography, like word and music, travels. In the age of social media and the internet, the photograph travels faster than the individual. Yet, few photographers are concerned with bringing the photo home – to its subject and origin of birth of the creation.

Abu Bakr and Ahmed are strong advocates of reaching every segment of Egyptian society to formulate a cohesive picture of the land’s inhabitants. They believe only through careful documentation, gazing, collaboration, and connection that photography of Upper Egypt can transcend the superfluous.

Comment (1)

[…] العودة إلى الوطن: معرض بشر الصعيد بالأقصر […]