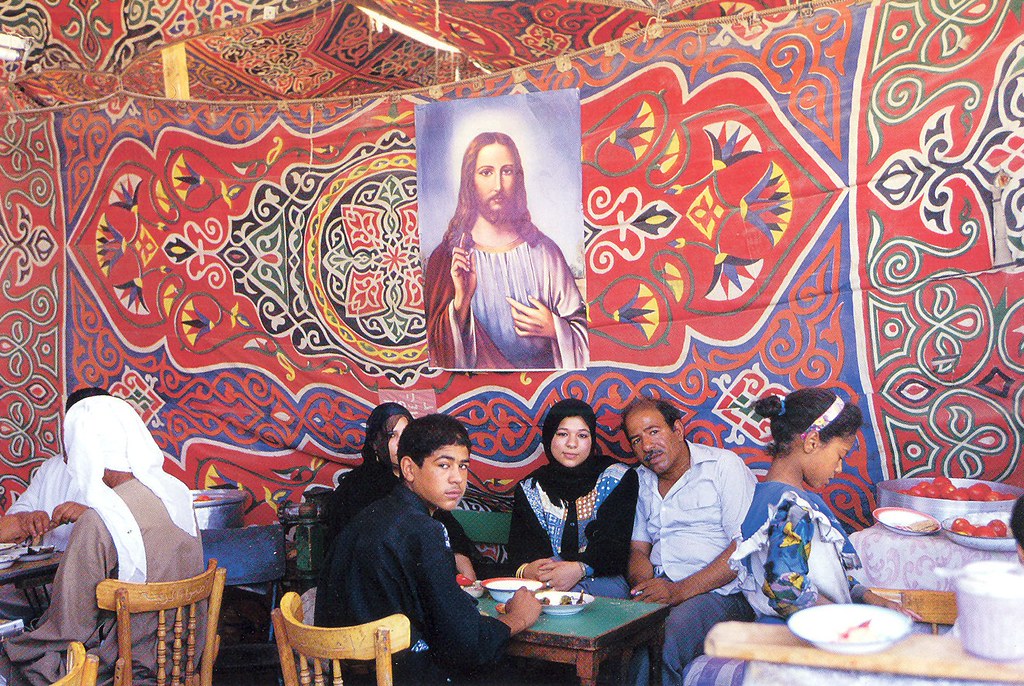

Sultry, moonless nights see the start of the mulid—the lights are vibrant and the shisha sweet, crowds swaying in trance-like prayer to tambourines and Islamic declarations of god is great, god is truth. Buildings are washed of color, draped over with carnival tapestries and graffiti. Women brush out braids and men swaddle grams of hash in newspaper triangles, knot string with their teeth; the marriage of tradition and religion sees a rebirth in one town square.

The mulid has begun.

Mulids are Egyptian saints-day festivals, characterized by a plural and dynamic character which makes defining them difficult. It has “never been possible to tell what a mulid is really about or how it is going to develop,” but despite the ambiguity surrounding the mulid, it has remained in public consciousness over the years.

Emerging alongside Islamic mysticism (Sufism) and the Muslim cult of saints, the mulid was believed to originate in the late Middle Ages. It embraced the extraordinary, and combined elements of religious pilgrimage, community carnivals, and public fairs. Ethnologist Samuli Schielke holds that a mulid is a “festival characterized by a profound ambivalence of experience;” it is a space for countless purposes.

Mulids tend to cover entire neighborhoods for several days, transforming cities into locales of cathartic celebration. Events include the reading of the fatiha at a saint’s shrine, taking rides on swing boats or ferris wheels, participating in dhikr (rhythmic, music-based meditation), and indulging in khidma (spaces for free food and lodging). Others choose to play dice and roulette on street corners, or listen to a munshid (religious singer).

The experience is a mix of cultural and religious rites that seem scattered and kaleidoscopic for the large part. While some will take the opportunity to feel more in tune with God, others treat mulids as a carnival: a loose and untamed exploration of the social self, without boundaries. Though the socio-religious aspects of the mulid are not its only features; for the majority of Egyptians, it is also an economic and political event.

It serves as a “platform where different vendors sell their products to the people who come from different regions in Egypt and as a platform for political figures to establish their images as religious or pious by attending some of the commemorations.”

Given mulids are a venerable commemorative tradition, they often take place on the birthday of a saint or martyr, with the term itself originating from the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birth. Mulid, at its most elemental, means ‘a birth’ — and for many, it is an annual rebirth of tradition and collective celebration.

Urban mulids are almost always associated with the urban structure of old city squares across Egypt where medieval shrines still stand. But due to its city-wide, chaotic nature, not many authorities are fond of the mulid’s practices; Islamic and Egyptian state officials have been vocal and vehement about contesting the mulid and its general air.

Religious officials have discredited the majority of mulid rites, deeming them bastardized and unrelated to Islamic tradition, while others view them as exoticised tradition “rejected as backwards by the discourses and imageries of modernity.”

In an effort to curb the chaos, and in some cases illicit activity, state authorities have taken to strict laws and regulations regarding any and all mulids. In 2020, the ministry of al-Awkaf officially banned all celebrations within mosques during mulids. While happily accepted by the Salafists and urban middle-class who oppose mulids due to their lack of Islamic authenticity, Shiite and Sufi communities deemed this an unnecessary, hostile action.

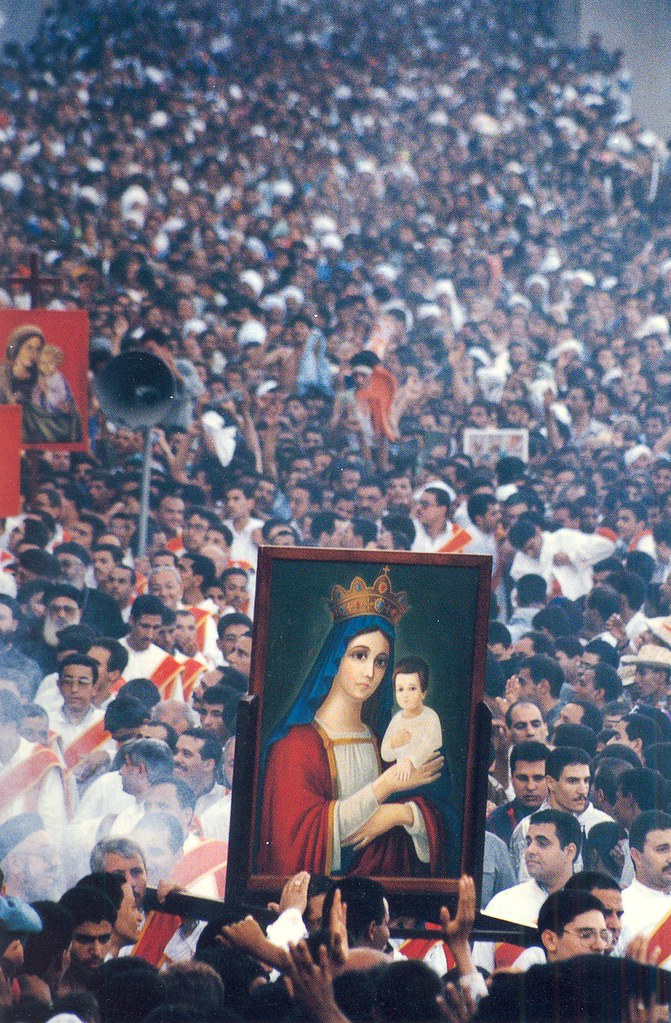

Although most famous for its Sufi origin, the mulid in Egypt has evolved to become a more adaptive, inclusive experience; many Coptic Christians celebrate their own mulids, most famously in the name of the Virgin Mary. Activities include tattoo stations, religious gift vendors, and opportunities for spiritual engagement such as religious music, sermons, and prayer shrines.

Despite being a polarizing tradition, the mulid has yet to fade: they still light up the nights with prayer and song, embellished with shisha smoke and syrupy black tea.

Comments (7)

[…] Chaos and Catharsis: Egyptian Mulids […]

[…] الفوضى والتنفس: الخلدون المصرية الحياة المأساوية لملكة مصر نازلي […]