“You’re not going to leave this wedding without a bride,” was how Mohamed Saeed was greeted upon his arrival at his best friend’s wedding.

As he danced the night away, he kept an eye out on all the single attendees, keen on soon celebrating his own wedding, and achieving the prophecy he was told.

Like any young Egyptian man, Saeed, a 32-year-old banker, entered some relationships-turned engagements in his 20s. Yet, none of these engagements led to marriage.

When he was 25, an arranged marriage had been an option many Egyptians, particularly older generations, were fond of. Nonetheless, Saeed wished to live a romantic love story that would end in a fairytale marriage, with hopes of living happily ever after.

“It was definitely not my favorite option, but I did not despise it or completely disregard it because I thought it resulted in many successful marriages. So, after multiple trials with love-based relationships, I was open to the possibility of an arrangement, and thought why not,” Saeed tells Egyptian Streets.

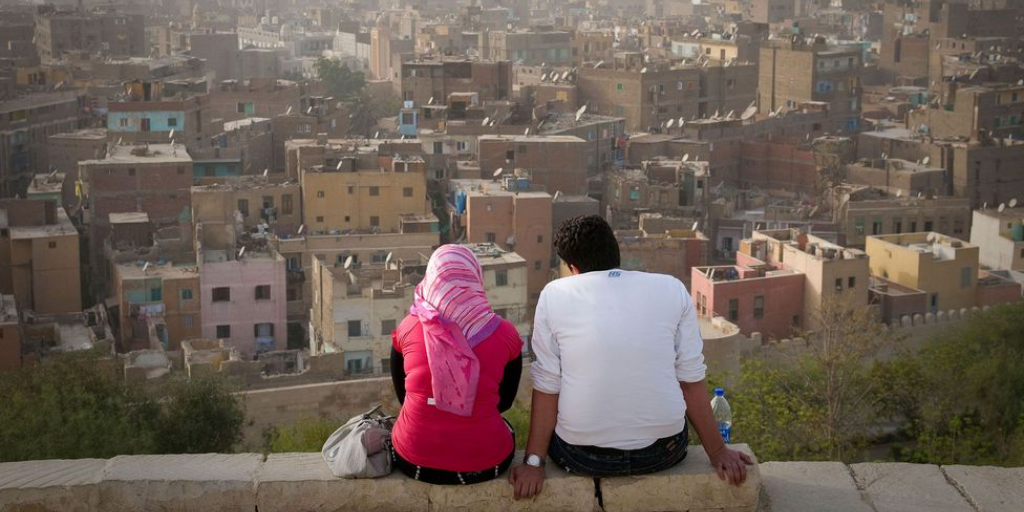

Saeed met his now-wife, Noha, at his best friend’s wedding. Upon seeing her, he felt inclined to get to know her, and after asking his best friend’s mother about her, it turned out they had been neighbors and family friends for years. They got to know each other under family supervision, and in a few months, they announced their engagement, soon to be wed.

“Gawaz salonat” (living room marriages) is the popular name for arranged marriages in Egypt. The name is derived from the tradition of couples meeting for the first time in the sitting room of the bride’s house, under the supervision of her family. The idea of arranged marriages is not fairly constructed. Long gone are days where suitors are forced to a mate for life, the ‘arrangement’ part merely implies a facilitation on behalf of external parties.

Indeed, today, arranged marriages come in different forms, sometimes facilitated through mutual friends, or even distant relatives.

It remains a popular option amongst those seeking to wed for the first time. For dating, online and offline, is still warned against by more stringent parents and families.

Eight years ago, procurement manager Marwa Ahmed was completely against arranged marriages. Today, at 36, she is nearly seven happy years into hers.

“I never wished to get married in an arranged marriage. I used to embarrass my friends and relatives when they tried to introduce me to a potential match,” Ahmed recalls.

For several years now, there has been an ongoing debate about the reason for the rising rates of divorce among Egyptian couples, and whether marriages where couples meet spontaneously and fall in love, are more successful, or arranged marriages. As it stands, one-fifth of marriages in Egypt end in divorce each year, with 40 percent within the first five years of marriage, according to a 2018 report by Egypt’s Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). The stakes are higher for Coptic Christians, who can only divorce under extremely strict conditions.

This, still, does not deter Egyptians from trying their luck to land a romantic, marriage match in a myriad of ways.

According to Ahmed, two individuals in love and in a relationship might oversee flaws and incompatibility issues, blinded by their emotions. On the other hand, arranged marriages give both sides a chance to get to know the positives and negatives of each other’s personality, deciding accordingly in the process.

“If he’s a womanizer for example, and I love him, I’ll say he’ll change after marriage. But if I see a personality trait like that in the case of an arranged marriage, why bother, it’s an immediate goodbye!” says Ahmed.

Ahmed explains that, in her experience with relationships based on spontaneous love, she had to compromise a lot. But with Khaled, her now-husband, she felt comfortable and they tied the knot three months after getting to know one another.

Arranged marriages bank on the idea of compatibility and suitability for marriage: age, professions and economic standings are often considered, along with character attributes and religious standing.

Meanwhile, Saeed, who describes marriage as chemistry between two people, believes that many young couples are more focused on “showing” that their relationship is working out, rather than actually building a strong relationship with their spouse.

“From romantic proposals to lovey-dovey social media posts, young couples are drawn towards a utopic life that does not exist in real marriage, and so with the first conflict, the relationship breaks down,” adds Saeed.

That is not to say that arranged marriages are bullet-proof. One quick glance at the plethora of social media groups making waves on Facebook reveal an avalanche of anonymized confessions and pleas for help: many, who have opted for arranged marriage, found themselves in a labyrinth of challenges. The ‘quick’ nature of arranged marriages, at times, leaves little room for properly discovering the match’s multifaceted nature: matches are revealed, post-marriage, to be stingy, abusive, or of a sexual orientation altogether.

Nonetheless, arrangements continue to be deemed safer than romantic relations.

There’s a popular Egyptian saying that many parents often reiterate, to convince their sons or daughters of a bride or groom that they chose for them: “El hob byegy ba’d el gawaz” (love comes after marriage).

Both Saeed and Ahmed, who went through the experience of an arranged marriage, agree.

“I used to think it’s a cliché sentence that is popularly used among the older generation, but I realized that it’s real. The bond that is created between a couple after marriage is stronger than anything they went through before marriage,” says Saeed.

“We never forget how we met; we always remember that wedding where we both first laid eyes on each other, and smile at those memories,” he concludes.

Comments (3)

[…] جديدة على المصريين. لقد ولت الأيام التي كان فيها فقط وسيط زواج كانت أم أو […]

[…] relationships are nothing new to Egyptians. Gone are the days when the only matchmaker was a mother or […]