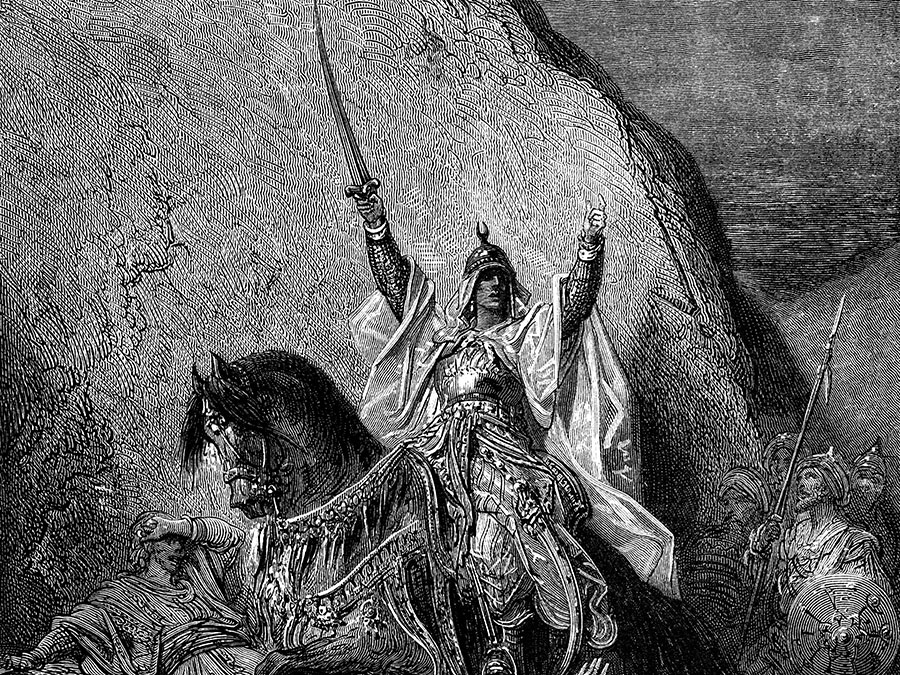

Mornings are riper in Aleppo; vibrant with the afterglow of victory. Baybars basks in it, but remains bitter; scars break the tan on his shoulders, battle-worn and time-sealed, and he thinks of how this city was meant to be his—made to be his. He approaches Sultan Quṭuz detailed in smile and courtesy, and with grace, cranes to kiss his hand. On that signal, the Mamlūks descend.

Quṭuz is speared through the neck, and Baybars—in a moment of euphoric fanaticism—seizes sovereignty.

He is now the most eminent of the Mamlūk sultans.

Born Tragic

Baybars I, also known as al-Zahir Baybars al-Bunduqdārī, is a controversial behemoth in Islamic history. Here was a man who sought to emulate Saladin, who married exalted vision with violence. There are few names more known or venerated; Baybars brought Egypt and Syria underwing, famously axed the final crusade, and time and time again fended off Mongol armies with renowned battlefield finesse.

Though the most famous Mamlūk was not Egyptian in origin.

Born in 1223 AD, north of the Black Sea in the country of the Kipchak Turks, Baybars was sold into slavery early on in his life. He was one of many Kipchak Turks who were dealt an unfortunate hand after the Mongols invaded their country circa 1242. Given that Turkish-speaking slaves had become indispensable and highly prized to Muslim armies at the time, Baybars soon found himself in the care of Egypt’s then-Sultan al-Salih Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb.

Trained militarily, Baybars demonstrated superlative skill on the field. After his graduation and emancipation, he was appointed head of the sultan’s personal guard. His first substantial victory came in February 1250 AD, as commander of the Ayyūbid army, in capturing crusader-king Louis IX of France.

Confident to the point of insolence, a group of Mamlūk soldiers headed by Baybars took it upon themselves to assassinate the newly appointed, final Ayyūbid sultan, Tūrān Shāh. At the behest of Shajarat al-Durr, supreme sultana and vicious politician, Baybars set the stage for a new era in Egypt.

The Mamlūk sultanate had begun.

An Era of Blood and Slave-Sultans

The storm would continue on into Baybars’ relationship with the first Mamlūk sultan, Aybak. After disagreement and hostility rioted between them, and with Shajarat al-Durr lying brutally executed at the base of the citadel, Baybars lost his footing in Egypt; he fled to Syria in 1260 AD, alongside countless Mamlūk leaders.

He would only return to Egypt at the pardon of the third Mamlūk sultan, al-Muzaffar Saif al-Dīn Quṭuz.

The very man he would come to kill.

Soon after, the Mamlūks would defeat the largest Mongol faction in the Levant. The battle took place near Nablus, Palestine, and throughout it, Baybars established himself at the head of the vanguard. For his victory, he expected nothing short of a grand gesture: he expected Aleppo.

Baybars was prone to dreaming, but quicker to anger—and when Quṭuz failed to fulfill this expectation, his end came swiftly after his mistake.

In his place, Baybars would take the throne as the sultan of Egypt and Syria.

Inspired, and perhaps infatuated by Saladin’s legacy, his immediate action was the fortification of Syrian citadels and the reinforcement of his military position in the region. He consolidated new factions, built new arsenals, warships, and cargo vessels—all of which had been depleted during continuous battle with the Mongols.

For decades he would simultaneously ward off the Mongols and conduct annual raids against the crusaders. In order to drive home this strategy, he united Egypt and Syria into a single, Muslim state that successfully took back the Levant from European control. ‘Atlit and Haifa were his, and soon after in the summer of 1266 AD, the Knights Templar would submit the town of Safed and Jaffa.

Though his triumph against the crusaders has gone on to be one of Baybars’ more histrionic accomplishments, his fixation on the Mongols was of equal fire: he saw them as an essence that “threatened the very heart of the Islamic East.”

Politics and Poison

Baybars legitimized his power by associating with a “fugitive descendent of the Abbasid dynasty,” and would go on to build internal, diplomatic infrastructure that would sustain the Mamlūks for centuries. Though political architecture was not the only building Baybars was prone to doing; he was keen on new projects, including harbors and canals, postal service, and mosques.

Baybars was also the first ruler of Egypt to appoint four qadis (chief justices) for the main schools of Islamic Law.

He was a devout Muslim and a generous almsgiver, even under the weight of his vicious disposition. But even kings are not immune to poison—or perhaps, they are most vulnerable to it. After drinking from a chalice intended for another man, Baybars would taste the bite of poison under his tongue.

He died in Damascus, in 1277 AD at the age of 54. Today, Baybars is buried under the dome of the al-Zahiriya Library in Damascus—a structure he himself built.

Comments (3)

[…] or El-Zaher, is a district that neighbors Abbaseya and Sakakini. Named after Al-Zahir Baybars, the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt,the term ‘Zaher’ translated to shine. The district houses Jewish […]

[…] ملك المماليك: الظاهر بيبرس […]