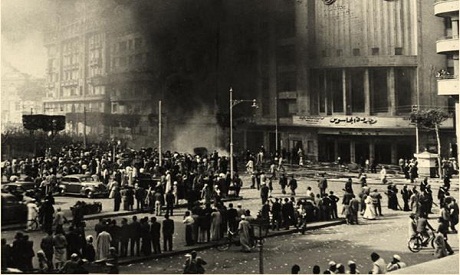

Currents of smoke rise into Cairo, and a fire that begins in the heart expands into the streets: riots smother the capital and arson overtakes the small, cobblestone streets of Wust el-Balad. Voices of opposition darken intent, and Egyptians rise from their humble homes to heed their own oppressed rage. It has been years of silence and servile dispositions; it is 1952 and the Cairo Fire is lit.

It is the beginning of the end for Egypt’s monarchy.

Described as “one of the worst acts of arson ever to hit the capital,” the Cairo Fire is shrouded in enigmatic narratives. Some chronologies blame enraged students and long-time demonstrators, others name the political forces opposed to King Farouk—who saw his confused relationship with the British as formal treason.

“We don’t know,” says renowned historian and Harvard University professor Khaled Fahmy, “and we can’t know [for sure].”

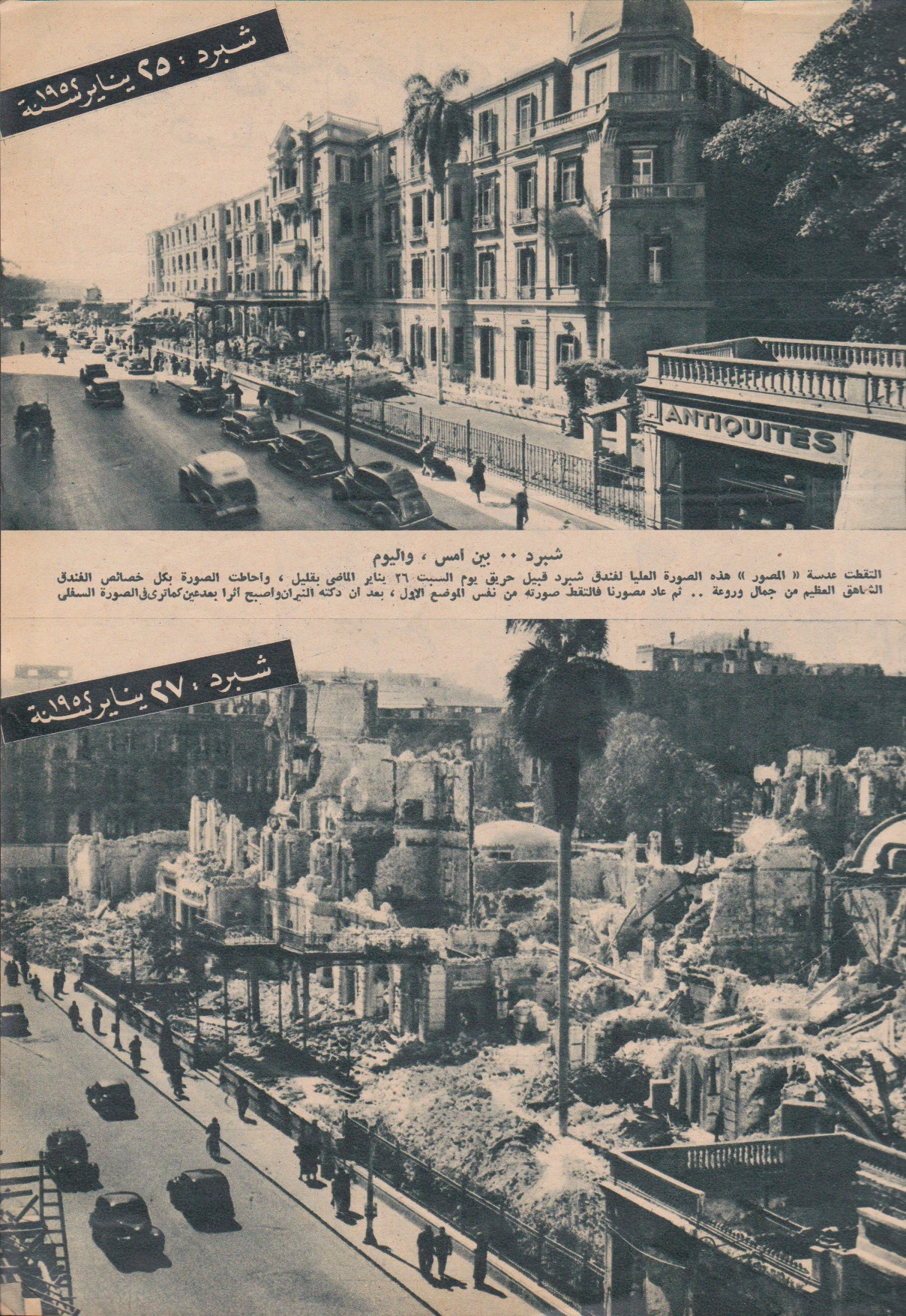

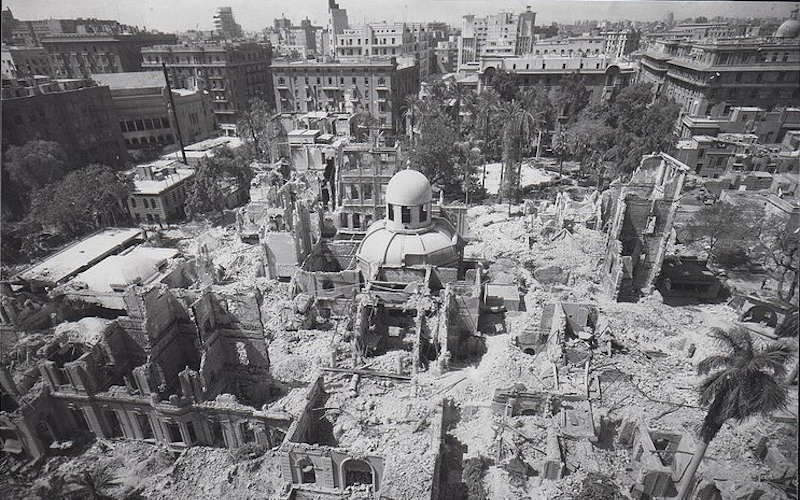

Though no known culprit has ever been identified, the source of the fire was born of a deep-rooted sentiment of colonial injustice. On what is known as Black Friday, 25 January 1952, the British occupation executed 50 Egyptian auxiliary policemen in Ismaliya, rousing an electric wave of fury. Vicious bouts of violence broke out on 26 January, with many iconic buildings burning as a result—including masterworks such as the Cairo Opera House and the 1860s Shepheard Hotel.

Riots came with dense, angry crowds and palpable, city-wide agitation. It was a “unified, uncontested popular expression of anti-colonial struggle,” a moment of “complete rapture” that saw anarchy overtake colonial ideologies; scholars argue that it was a moment of simultaneous rage and celebration, an outcry that begged for cultural, social, and economic transformation.

These were the events said to have led to the 23 July military takeover led by Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Free Officers Party, which would not only overthrow the Egyptian monarchy, but put a firm and resolute end to British colonialism in Egypt. The events of the Cairo Fire and its complementing riots would continue to influence the way in which modern and post-modern Egyptians expressed their political and social frustration for decades to come.

This one incident—a flurry of violence and wilful destruction—marked a moment in Cairo’s history wherein the past was vilified in favor of a newfound nationalism. Colonial symbols and architecture were destroyed, and privileged spheres were humbled as a result.

Despite this, it is something of a forgotten historical skid-mark: a catalyst never studied independently of the 1952 coup d’état. Documents on what truly happened that day remain in state custody, unreleased to the public, which only serves to feed into general curiosity. The day of Black Friday, and the subsequent Cairo Fire, are incomplete in the public mind and prone to romanticization.

Put best by Fahmy himself, “acts of arson do happen during moments of political upheaval, and confrontations between the police and demonstrators end up with causalities, but it is important to know what really happened—not to vindicate but to understand.”

Comments (3)

[…] A Night of Anarchy: Black Friday and the 1952 Cairo Fire Egyptian Streets […]

[…] ليلة من الفوضى: الجمعة السوداء وحريق القاهرة 1952 […]