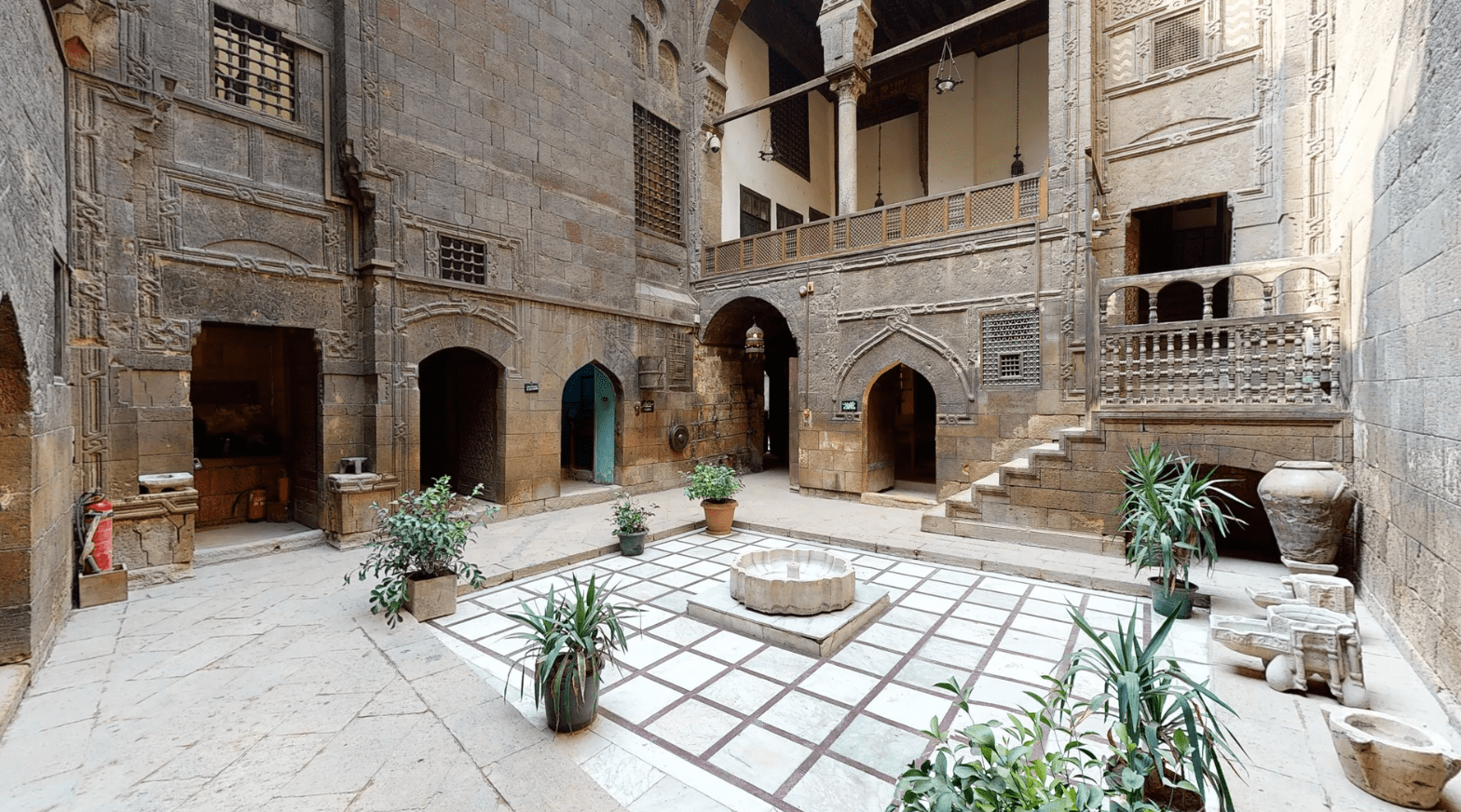

Mashrabiyas sweep light across square halls, the corridors linking each room embellished with fine detailing and glassed artifacts. A vertical staircase is the spine of the estate, branching out into a high ceiling more akin to wooden skies than canopies. A film crew sits in the courtyard, by the fountain, and they murmur Gayer-Anderson in soft, accented Arabic.

The museum is silent otherwise.

The Gayer-Anderson Museum, also known as Beit al-Krittliya (House of the Cretan Lady), is a niche spot, tucked in the downtrodden avenues of the Sayeda Zeinab district. Graffiti welcomes visitors, and men in jalabiyas (traditional Egyptian dress) offer kindness with a guiding hand. On the outside, it is little more than a function of two medieval Ottoman houses: arabesque domes and sanded stone, Islamic architecture at its most domestic. On the inside, the museum becomes a world unto itself, packed with artifacts dating millennia from across the globe.

Adjacent to the medieval beauty that is the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, the whole area dates back to the Mamlūk period of Ottoman history. The twin houses, now known as the Gayer-Anderson Museum, were believed to have been built between the 16th and 17th centuries; the first house was commissioned by scholar Abd al-Qadir al-Hadad in 1545 AD, and later came into the ownership of a certain Lady Amina bint Salem. The second house was built in 1631 AD, connected by a later-added corridor, and belonged to Hajj Muhammed ibn Jilmam al-Jazar.

Different families came to own the property until it fell to a woman from Crete—hence its alternative title, Beit al-Krittliya. Its central namesake, however, was Gayer-Anderson Pasha: a man charged with intellect and curiosity, who saved the Ottoman houses from demolition in 1935. He was an Englishman who gnawed away at a medical degree in London, before being deployed to Egypt as a lieutenant in 1907. Between his life as a surgeon and soldier, and his profound interest in Egyptology, Gayer-Anderson became a “portrait of a multifaceted and enigmatic figure.”

Walking through the houses, one sees a man of many languages, a creature dedicated to knowledge in every capacity.

In the early winter of 1935, Gayer-Anderson requested to live in the houses and finance their refurbishing; the Assembly of Preserving Arab Antiques agreed, insofar that his collection—and the houses—would be returned to the Egyptian government following his death, or if he ever chose to leave Egypt. Over the years, he collected pharaonic, Islamic, and Asiatic antiques; Mamluk fort doors, Chinese tea sets, and handwritten Quranic verses—the two homes are dense with history, kaleidoscopic in nature.

Pharaonic writing tablets, Islamic paintings, medieval Asiatic dining salons: Anderson’s collection is a strange and unlikely assemblage—some would argue wholly immoral, had this not been a banal form of appreciation in the late 19th century. Anderson’s retirement gave him time to curate his own, personalized collection that catered to his personal tastes.

From Beijing artifacts to the heart of al-Sayeda Zeinab, it becomes more and more apparent how exhaustive and elaborate Anderson’s collection was. He had a “knack” for finding exceptional pieces, choosing to live among them as an homage to their richly saturated histories.

While all ornate and well-kept, halls vary in nature and name. The Indian Hall and Chinese Halls are renowned for their still-intact beauty, while Queen Anne Hall revisits Anderson’s English inclinations.

In 1945, due to failing health, Anderson left for England and handed the property over to the Egyptian government. Shortly after, it was preserved and transformed into the museum individuals visit today. Gayer-Anderson’s homemade museum attracted many visionaries over the years, and perhaps most interestingly, was the site of a James Bond movie, ‘The Spy Who Loved Me’ (1977).

Although initially promising to leave all within the houses to Egyptian authorities, pieces of Gayer-Anderson’s collection made their way to England, and today remain featured in the British Museum. This includes an antique ancient Egyptian cat sculpture, now known as the Gayer-Anderson Cat. The question remains as to how ethical this exchange was, given Anderson’s previous agreement with the Assembly of Preserving Arab Antiques.

While a colonial past cannot be commended in good faith, the small, hand-held world Anderson built in the heart of Egypt remains a fond and breathtaking reality.

The museum is located in the Sayeda Zeinab district. Adult tickets for Egyptians/Arabs are EGP 10 per person and EGP 5 for students. For foreigners, the adult fee is EGP 60, and the student fee is EGP 30.

Comments (4)

[…] […]

[…] Source link […]