The Arab world is rarely thought of as a hotspot for science fiction. The kinds of Arab stories that rise to international acclaim are usually social issue dramas, documentaries, or tales of refugee struggles.

Nonetheless, in recent years, the tides of genre in the region have changed. From Ahmed Saadawi’s 2013 novel Frankenstein in Baghdad and Ahmed Khaled Tawfik’s 2012 Utopia, to Meshal AlJaser’s 2020 film Arabian Alien and the animated sci-fi series Ajwan, in the past decade, Arab science fiction (ASF) has increasingly caught the attention of audiences and critics worldwide.

Contrary to popular belief, however, ASF is not a new genre. Arab countries have long been home to a rich and vibrant science fiction tradition — one which is closely intertwined with colonialism and political resistance. Some evidence even points to the possibility that the genre was invented in the Arab world. Why, then, has sci-fi historically been associated with the West?

Science Fiction and Colonialism

While the genre’s origins have been the subject of debate, modern science fiction is largely believed to have originated in 19th century Europe, during the continent’s transition into the industrial age.

These early works of sci-fi told stories of uncharted worlds, futuristic machinery, and strange species, based on the discoveries made during expeditions to the ‘new world’ three centuries prior.

For example, Jules Vernes’ 1872 novel, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, follows the Nautilus ship on its submarine adventures, during which the sea captains encounter a creature resembling a giant narwhal: a type of whale found in the arctic waters of Greenland and Canada.

A key aspect of science fiction, according to scholar Ian Campbell, is its colonial underpinnings. In fact, early examples of the genre were often replete with references to hostile natives inhabiting the faraway lands where protagonists dared to venture.

For instance, H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel, War of the Worlds, openly reflects on Victorian anxieties about race, with aliens in the story representing the people of color whom the British increasingly encountered through colonial invasion. Even Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein can be and is often read as a commentary on slavery and race.

Based on these origins, Campbell defines Western science fiction as stories of colonial encounters told from the perspective of the occupier.

For this reason, he argues that ASF is “an archetypally postcolonial literature, in that it uses the language of the colonizer—the tropes and discourse of science and of SF—to examine, critique, and even resist that colonizer’s power.”

Based on these origins, Campbell defines Western science fiction as stories of colonial encounters told from the perspective of the occupier.

For this reason, he argues that ASF is “an archetypally postcolonial literature, in that it uses the language of the colonizer—the tropes and discourse of science and of SF—to examine, critique, and even resist that colonizer’s power.”

This theory is supported by the rise of ASF in the mid-20th century, as countries of the region sought independence from their Western occupiers.

In Egypt, writer Youssef Izzeldin Issa popularized science fiction radio broadcasts in the 1940s. In the 1960s, Mustafa Mahmoud authored several landmark science fiction stories, like The Spider (1965) and A Man Under Zero (1966), often bringing science into conversation with religion.

The genre gained unprecedented traction during the presidency of Gamal Abdel Nasser, who stipulated that Pan-Arabism, non-alignment, and socialist politics would allow Middle Eastern nations to participate in the international space race — a phenomenon which occupied a special place within ASF throughout the Cold War.

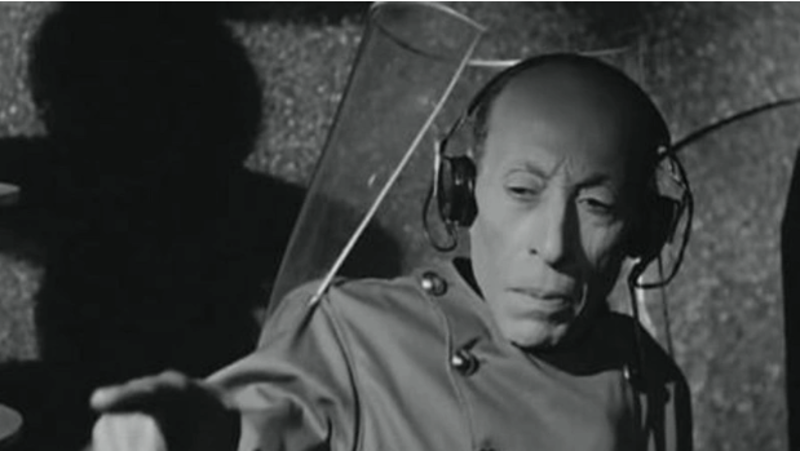

In January 1958, for instance, the Cairo-based cultural magazine Al-Hilal produced a special issue on “The Moon Epoch” in Egyptian nationalism. The following year, iconic actor Ismail Yassin starred in the film Journey to the Moon, a space travel adventure complete with cardboard robots, drinking games, and dance numbers.

Behind its comical jab at space exploration, the film hides a subtle critique of the bipolar politics of its era. Other works were more overt in their denunciation of Cold War dynamics, like Tawfik Al Hakim’s 1972 play, A Poet on the Moon, which likened the moon landing to colonial invasion and an imagined alien population to the occupied people of the Third World.

For the most part, these works adapted existing Western novels and film, infusing their storylines with sharp criticisms of imperialism and cultural hegemony. Within its futuristic settings, ASF posed the question of who and what the Arab people were outside of colonial occupation.

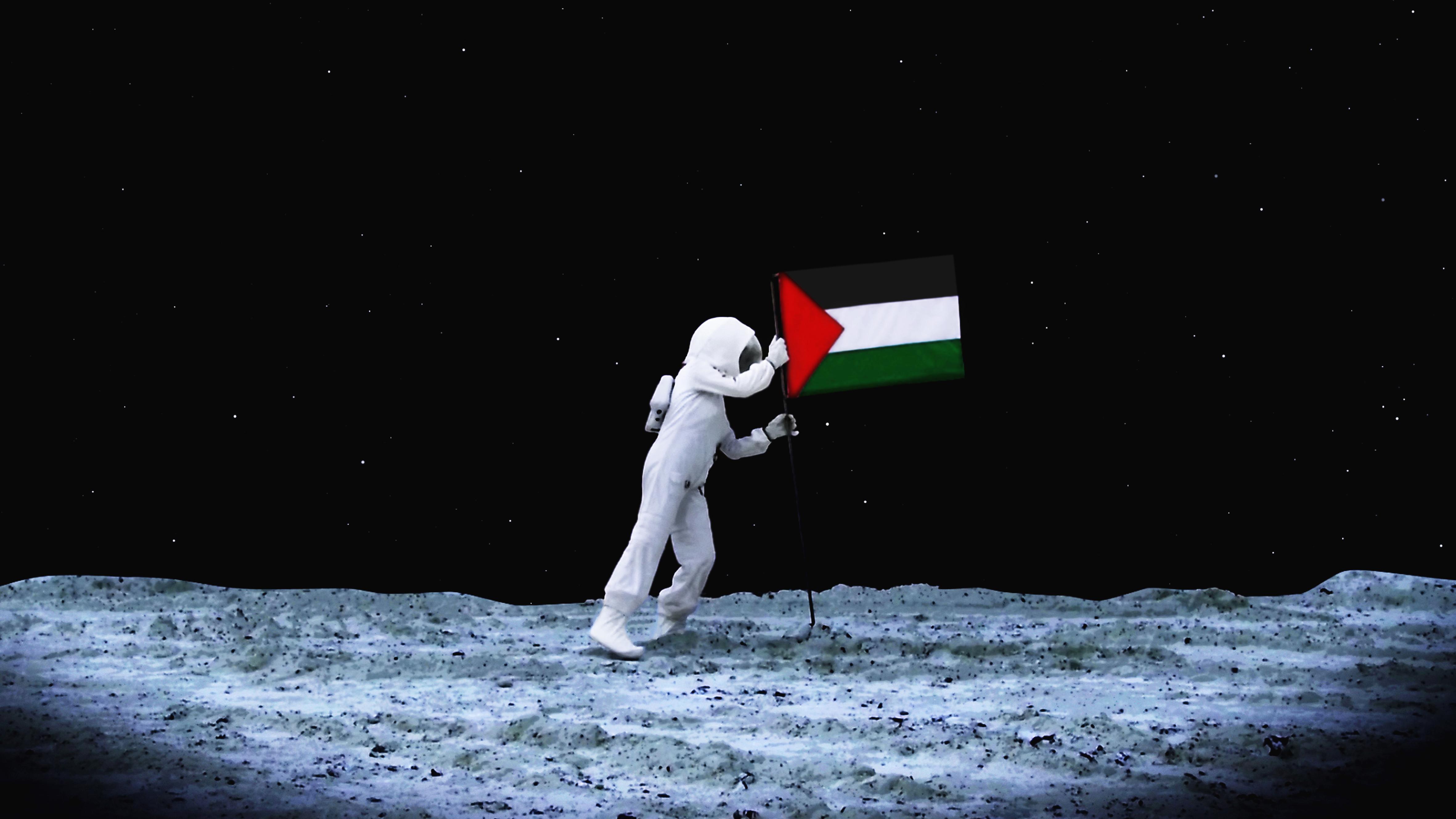

The tradition of ASF as postcolonial resistance continues today. One representative example is Palestinian filmmaker Larissa Sansour’s sci-fi trilogy, comprising A Space Exodus (2008), Nation Estate (2012), and In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain (2015).

The first film in the trilogy, A Space Exodus is a play on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, an ode to human progress and evolution from the stone age to the moon landing. In Sansour’s film, a lone astronaut embarks on a spaceship and plants her country — Palestine’s — flag on the moon. Through this act, she posits that real progress is not technological prowess, but postcolonial liberation.

The second film, Nation Estate, is perhaps the most glaring example of what Campbell describes as reclaiming the tropes of science fiction to combat colonial oppression. In the film’s dystopian world, all of Palestine has been compressed into one massive skyscraper in the West Bank, where each city occupies a floor of its own.

The protagonist (played by Sansour) rides the elevator up to her apartment in ‘Bethlehem.’ The stale studio displays a few architectural features of the city and elements of Palestinian culture: a miniature olive tree, a keffiyeh (the traditional Palestinian scarf), and local food served in self-heating cans.

The bright colors of these local staples sharply contrast with the apartment’s white walls and plain furniture. Like Sansour herself, they look out of place, uncomfortably crammed into this hyper-futuristic estate — an analogy of how Sansour imagines Palestinians would be within the proposed antidote of a two-state solution.

In the film’s final scene, the protagonist presses a button which lifts a virtual white curtain from her windows, unveiling the real West Bank. She places a hand on her stomach, revealing she is well into her pregnancy, then stares emptily out the window.

We quickly understand why she derives no joy from her impending motherhood. Under occupation, the promise of new life also brings the painful knowledge that yet another Palestinian will grow up forcibly displaced.

Through her reclamation of sci-fi elements, Sansour not only critiques Israeli colonialism, but also the international community’s superficial response to the crisis. What Sansour also denounces is the appropriation of Arab cultural symbols and traditions by the West — a phenomenon which lies at the very core of science fiction’s history.

Reclaiming an indigenous tradition

Ian Campbell’s Arab Science Fiction was among the first books to undertake a comprehensive history of ASF, but does not delve into pre colonial iterations of the genre in the Arab world – even though the genre’s history might go back much farther than colonialism.

Some have recognized Ibn Al-Nafis 13th century theological epic, Theologus Autodidactus, the dystopian tale of a feral child who is spontaneously generated in a cave and lives alone on a desert island, as the first prototypical sci-fi novel. Another contender for the title, from the same period, is Zakariya al-Qazwini’s Awaj bin Anfaq, the story of an alien’s strange encounters with humanity.

Going back even earlier, the legendary anthology comprising folk tales from the Islamic Golden Age, One Thousand and One Nights, can also be thought of as proto-science fiction, introducing stories of underwater exploration and space travel.

Why, then, did ASF wither into oblivion for so long before its resurgence in the twentieth century? Speaking to the BBC, British-Pakistani writer Ziauddin Sardar offered one explanation: In his view, when the Islamic Golden Age came to a close, the Muslim and Arab worlds escaped into their glorious past to avoid looking into an increasingly bleak future.

If Sardar’s words hold true, the revival of sci-fi at the height of independence movements in the 20th century may have been a sign of rebellious optimism.

Science fiction may or may not have originated in the Arab world, but what is undoubtedly notable about ASF’s history is that it corresponds to moments of upheaval in the region.

When sci-fi first appeared in the 13th century, the Muslim world was experiencing widespread change at the outcome of the Crusades, a defining era for both East and West. When the genre was first revived in the 1940s, the Arab people were resisting occupation and struggling to define their identity outside of Western occupation and hegemony.

It is also noteworthy that the most recent wave of ASF followed the Arab Spring, another period of regional upheaval. A now classic example from Egypt would be Ahmed Khaled Tawfik’s 2012 Utopia, a dystopian novel set in the year 2023 and providing a grim look into the growing class inequalities that have continued to plague the country ever since.

Science fiction, therefore, has long served a mirror into the anxieties, hopes, and aspirations of the region. Perhaps the genre’s resurgence today means that Arabs are once again looking to formulate pathways for resistance, redefining our identities, and dreaming of a better tomorrow.

Comments (4)

[…] window.speakol_pid = 29 (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Between Resistance and Heritage: Science Fiction in the Arab World […]

[…] Between Resistance and Heritage: Science Fiction in the Arab World An All-Woman Playlist: North African and Arab Artists to Listen to in 2023 […]