As part of Cairo Photo Week, Downtown Cairo’s Access Art Space is hosting an exhibition entitled ‘The Legend: Farouk Ibrahim.’ Curated by visual artist Nadia Mounier, the exhibition celebrates the iconic photographer’s legacy with a display of over 150 photographs unboxed by his son, Karim Farouk Ibrahim.

At the gallery’s entrance, visitors are greeted by two images hanging on either side of the opposite wall.

One shows the members of the 1952 Revolutionary Command Council, who led Egypt’s uprising against the monarchy and transition into a republic. The second picture, captured in Tahrir square in February 2011, shows a middle-aged couple raising a flag in proud celebration of the downfall of Mubarak’s thirty-year rule.

The two images swiftly alert viewers to the historical value of the archive on display. Active from 1952 until his death in 2011, Ibrahim’s body of work spans sixty years and two revolutions.

As such, it provides an opportunity to reflect on the tumultuous social, political, and cultural change witnessed in those six decades, and the power of photojournalism to provide a counter narrative to dominant historical accounts.

Decolonizing Egyptian Photography

Ibrahim’s work is given particular significance when viewed in the historical context of photography in Egypt. For centuries, the only images of Egypt seen by the West were Orientalist portrayals of the country as a strange and exotic otherworld.

In the late 19th century, photography became a means to archive the remnants of ancient Egyptian civilization, but also, the daily lives of common people. Nonetheless, the images captured by Western photographers were often highly curated, staged portraits clinging to the exotic allure of Orientalist art.

It was not until Egyptians themselves began to step behind the camera in the 20th century that more truthful accounts of the country emerged. Farouk Ibrahim was a pioneer in this regard, providing candid representations of Egypt’s many facets – from the tales of the rich and powerful to the unsung stories of the ordinary.

The first room in the exhibition is an introduction to Ibrahim’s life and work as a photojournalist at Akhbar Al Youm newspaper, where he began his career as a teenage office boy before growing into one of Egypt’s most celebrated photographers.

Pages of the newspaper bearing his photographs hang over a glass case filled with relics of his career: his syndicate card; press passes for parliament meetings, presidential visits, and trips to the far corners of the world; official letters and invitations; a roll of film capturing images from the signing of the Camp David Accords.

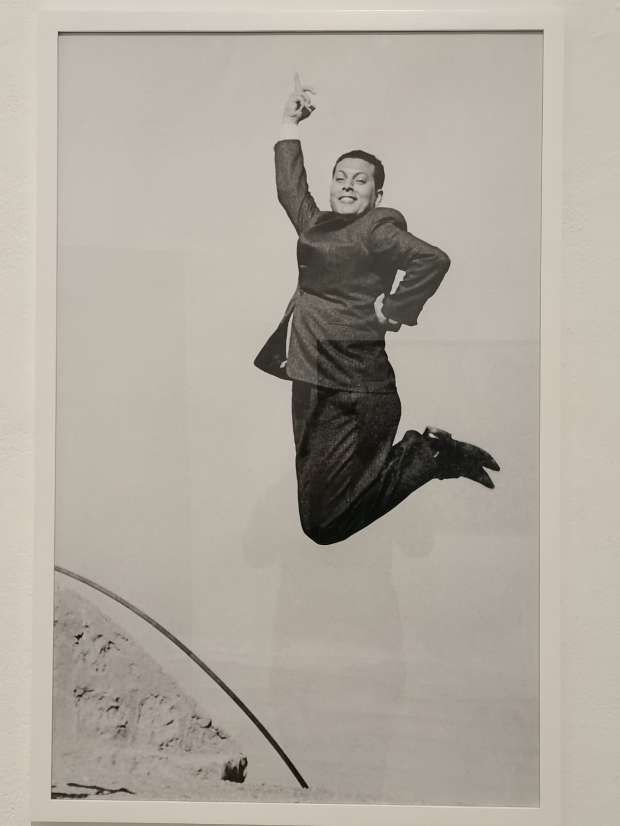

Beside them is a portrait of the artist jumping up gleefully, one hand tucked into his side, the other, raised to the sky – seeming to welcome visitors aboard the journey ahead.

Ibrahim is famous for having worked with all three presidents who ruled during his life; namely, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar El Sadat, and Hosny Mubarak. Within the exhibit, three rooms show various aspects of life during their respective presidencies.

We see Nasser greet admirers during a public speech, crowds celebrating Egypt’s victory in the 1973 war, Sadat signing the Camp David Accords, and images of Hosny Mubarak alongside his son, Gamal. Also on display are pictures of every era’s cultural icons: from Umm Kulthum, Roshdy Abaza, and Abdel-Halim Hafez, to Izzat Abo Ouf, Laila Elwi, and Amr Diab.

The collection is an archive of the uprisings, events, and historical personalities who shaped the country through the decades. Yet, just as prominent in Ibrahim’s repertoire of work are the legions of people whose names history did not preserve.

The Nasser room also houses pictures of National Circus performers at the Tora Prison in 1963, performing for a crowd of guards and detainees; manual workers toiling through the construction of the Aswan High Dam; and two men in jalabiyas purchasing tickets for the 1968 film Kandil Umm Hashem (Umm Hashem’s Lamp).

The Sadat room shows crowds bid the president farewell on his way to sign the Camp David Accords, their expressions ranging from glee and adoration, to simple intrigue, and even seeming discontent – a panoply of public responses to the historical peace treaty.

Umm Kulthum’s death after a battle with heart disease, a moment of nationwide grief and tragedy, is told not through her impressive public funeral, but through the image of two crying nurses outside of her hospital room.

In the Mubarak room, color has seeped its way into most photographs. Photos of the former president consist primarily of official portraits and press conferences held before massive posters of his likeness, but he is seldom seen interacting with the wider public. Visuals of ordinary citizens’ lives, meanwhile, seem divorced from these prestigious settings.

They include commuters reading books on public transit, butchers selling meat on the Nile Corniche, two pairs of hands holding up masses of winged insects during Egypt’s locust epidemic in 2004, and a family housed under a tent on the pavement after the 1992 earthquake — interestingly, the only event rendered in black and white in the room.

With each historical turn, Ibrahim’s work provides visitors with both the official record and the story of those to whom it did not give voice. Through this flurry of faces, we are reminded that while history may be written by victors, it is also built on the shoulders of ordinary citizens.

Demystifying Power and Fame

A core and widely celebrated feature of Ibrahim’s work is the intimate lens through which he captured his subjects. The late photographer did not only give weight to ordinary citizens, but also strove to shed humane light on those whom cultural memory sometimes elevates to divine status.

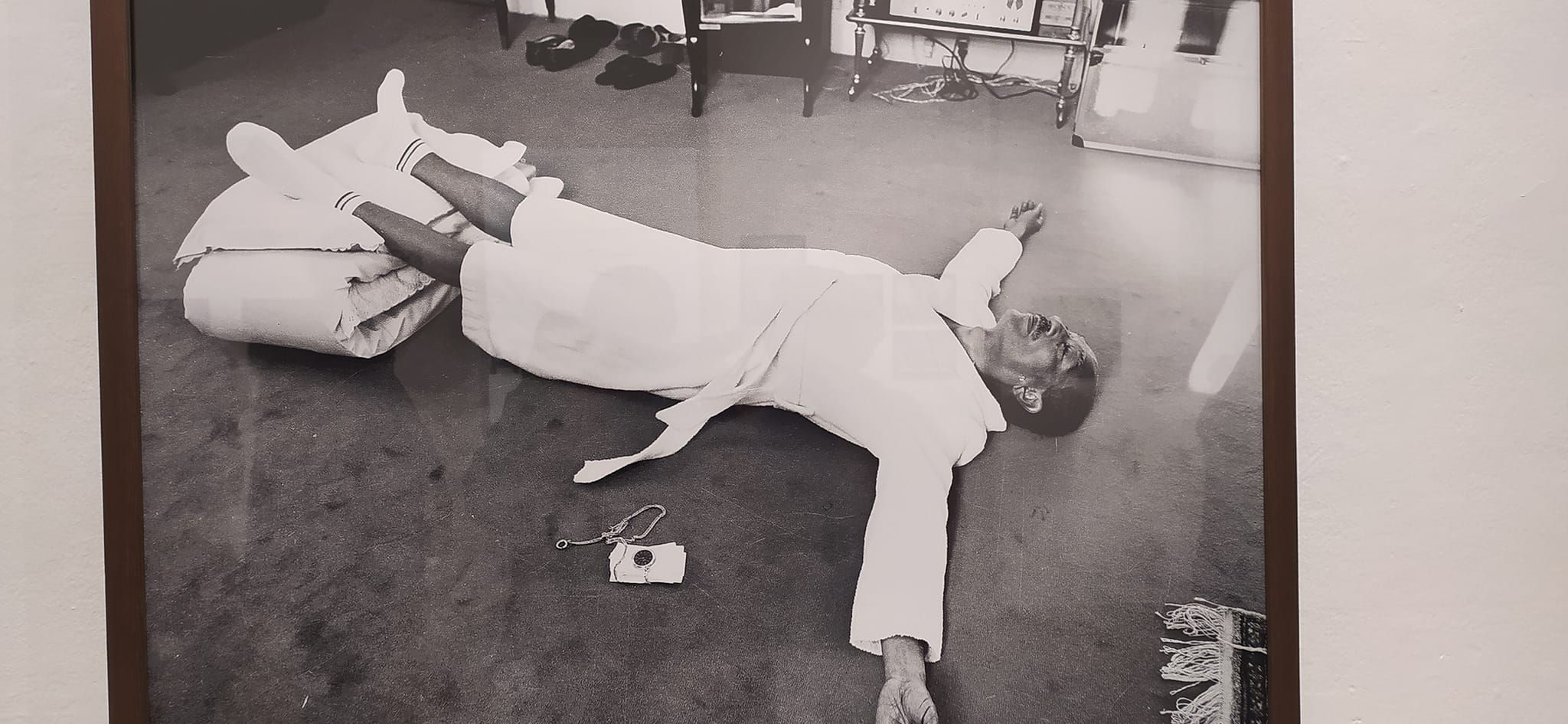

One example is his notorious photoshoot portraying a day in the life of Anwar El Sadat. The images show Sadat going about the same morning rituals as most people do: shaving in front of a bathroom mirror in his underwear, laying down in his room, and reading the newspaper.

Following their release, the pictures sparked widespread criticism. The president, whom most citizens knew only through official photographs, speeches, and public appearances – all highly curated encounters – had chosen to be seen the way one is only seen by those closest to them. To many observers, this seemed unbecoming.

Two photographs from the series are displayed at the exhibition. One is a cover of Akhbar Al Hawadeth, showing Sadat shaving in front of a mirror and bearing the caption “the pictures of Sadat that threatened the king of photography in Egypt!” – a reference to the aforementioned controversy.

The second photograph, occupying the right half of an otherwise uncrowded wall, shows Sadat in a bathrobe, lying on the floor with arms spread out at his side and feet resting atop a pile of towels.

In both pictures, Ibrahim’s own reflection can be seen in the mirror, a candid reminder of the mediated process of photography, but also of Sadat’s own agency in the shoot and in this atypical representation.

The photographer’s oldest son, Hesham Farouk Ibrahim, recounted in an interview with the DMC channel that the series was born when Ibrahim attended a press conference during which only one American photographer was allowed to step over the cordon separating the president from media attendees.

After learning that the foreign journalist had in fact been hired to create a book about Sadat, Ibrahim wrote a long letter asking the president to offer this opportunity to one of Egypt’s own local talents instead; to which he obliged.

This origin story is telling of the barriers, both physical and metaphorical, that stand between the political or cultural elite and the Egyptian public — ones which Ibrahim worked to deconstruct through his bold request and ensuing artistic project.

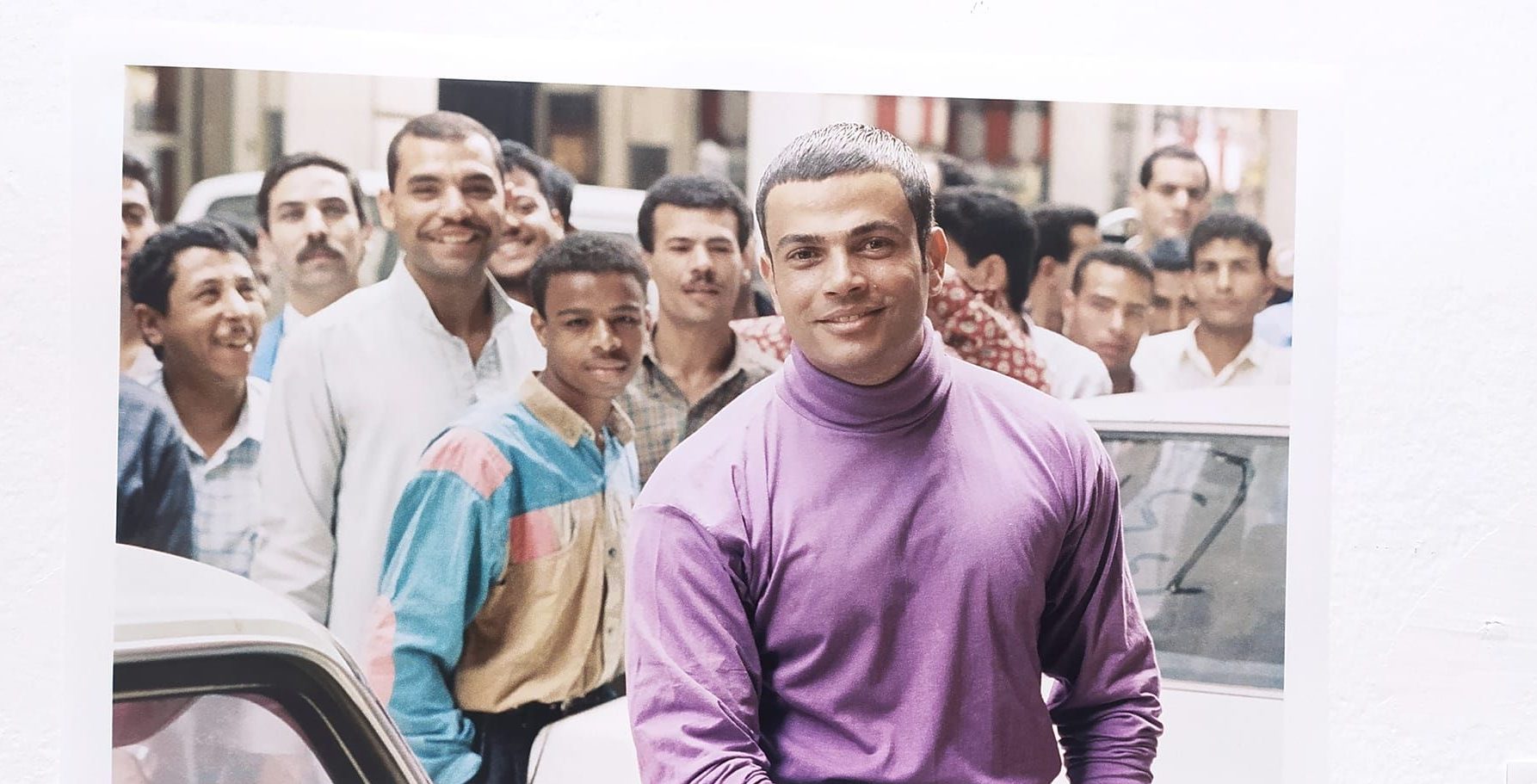

The same demystifying process permeates Ibrahim’s photographs of cultural icons and celebrities, whom he came to know both through his work as a photojournalist and his brief ventures into the world of cinema as an actor.

In the final room of the exhibition, pictures of celebrities are pinned to clotheslines against rugged yellow walls, emphasizing the contrast between the subjects’ prestigious social standing and the candor of the portraits.

Visitors see Umm Kulthum, Lady of Arabic Song, freshening up in front of a mirror; a young Sherihan practicing ballet at the dawn of her career; legendary couple Shouweikar and Fouad El Mohandes in bed; the iconic Souad Hosny on a film set, rollers still holding up her hair.

The gallery also houses numerous pictures of Abdel-Halim Hafez, a lifelong friend, whom Ibrahim captured in parks, on trips abroad, or laying on a couch in the comfort of his home, all uncanny portrayals of the legendary artist.

Through his intimate chronicling of their lives, the photographer stepped away from the ethereal glamor of celebrities to offer his viewers a portrait of mortal men and women – in many ways untouchable, and in many others, human and vulnerable.

The pictures are displayed by the dozen, side by side, collage-style. While perhaps simply owed to spatial restrictions, this curatorial decision serves to present the images not as singular odes to the artists, but rather a mosaic of Egypt’s rich cultural heritage.

Speaking to Akhbar Al Youm, where he also works as a photojournalist, Karim Farouk Ibrahim explained that the exhibition was primarily intended to share his father’s work with young photographers, offering them the chance to learn and draw technical and artistic inspiration from his legacy.

He went on to note that while the curation aimed to create a logical flow between the images on display, the scarcity of written explanations was also an intentional feature of the exhibition.

Left to wander the gallery with limited guidance, visitors are indeed free to connect the dots of Ibrahim’s decades-long career and, by extension, the historical nuances underlying each of the photographs on display.

This extensive archive speaks to the power of photojournalism as a means to preserve and recount history in all its most memorable and seemingly benign facets. The pictures are not only a reminder of the consecutive waves of change that have swept Egypt since the 1950s, but also of those responsible for them – from the grandiose to the powerfully ordinary.

Comments (4)

[…] Read More […]

[…] = 29 (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Remembering Farouk Ibrahim, Pioneer of Egyptian Photography How Many Days Do Coptic Orthodox Christians […]