In ‘Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity,’ Egyptian film historian Viola Shafik describes Palestinian cinema as a “national cinema without homeland” – a designation owed to the fact that most of the country’s practitioners live in diaspora, rely on foreign funding, and are barred from showing their films in the Occupied Territories.

And yet, through the decades, Palestinian filmmakers have managed to reach the world with their stories and reap international recognition; both for their work and for Palestine.

The first Palestinian film is generally believed to be a short documentary directed by Ibrahim Hassan Sirhan in 1935, recording the King of Saudi Arabia’s visit to Palestine. Ten years later, Sirhan founded the Arab Film Company with producer Ahmad Hilmi Al-Kilani. It produced only one feature film, ‘Holiday Eve,’ before its operations were cut short by the Nakba in 1948.

For the next two decades, occupation, displacement, and Arab military defeat brought film production to a near-total halt. It was not until 1968 that the industry began to rise back from the ashes, becoming deeply entrenched with the broader struggle for liberation – as it has been, in varying ways, ever since.

Below are six films representing different eras and key developments in the history of Palestinian cinema, for a small first glance into this resilient body of work. All films mentioned below are available on one or more streaming platforms.

They Do Not Exist, directed by Mustafa Abu Ali (1973)

In the late 1960s, Palestinian cinema reemerged under the auspices of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and other political groups. Most of the films produced during this period were documentaries directed by filmmakers living as refugees in neighboring countries – whose works were screened internationally, but never in their homeland.

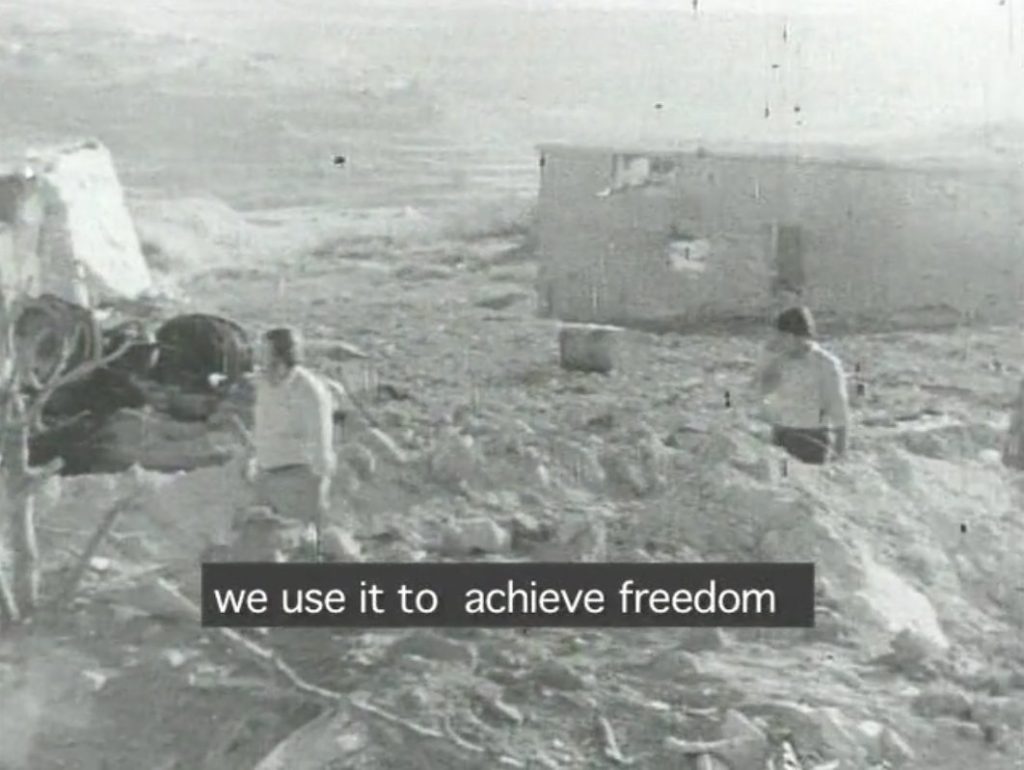

Among these exiled pioneers was Mustafa Abu Ali, who co-founded the Palestine Film Unit in Jordan in 1968. In an interview, Abu Ali explained that “the Palestinian resistance believes that action through cinema is a natural extension of armed action.”

Illustrating those words, his 1973 film, ‘They Do Not Exist,’ borrows its title from former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir’s infamous quote, “there was no such thing as Palestinians.” Shot in Lebanon’s refugee camps, the short documentary chronicles the living conditions of their inhabitants.

The film won the Diploma of Honor at the 1974 Leipzig Film Festival and the prize of the Arab Critics Union at the 1978 Carthage Film Festival; and had its Palestinian premiere in Jerusalem in 2003, during a screening hosted by filmmaker Annemarie Jacir.

‘They Do Not Exist’ is available to watch on Vimeo.

Wedding in Galilee, directed by Michel Khleifi (1987)

In 1982, the PLO’s film archive in Beirut disappeared along with the rest of its cultural heritage collections, shortly after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Meanwhile in Palestine, this tragedy partly prompted a new generation of filmmakers raised within the 1948 territories to shift their focus to local life, culture, and tradition – resisting the prospect of cultural genocide.

Among these filmmakers was world-renowned auteur Michel Khleifi, whose 1987 film ‘Wedding in Galilee’ became the first Palestinian film to receive the International Critics Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and attests to the role of cinema as a tool for cultural archivism.

In the film, the mayor of a small West Bank town (Mohamad Ali El Akili) wants to throw his son a traditional wedding. To this end, he requests a suspension of the curfew imposed by Israeli authorities. The occupying governor agrees – but on the condition that he and his fellow law enforcers be allowed to attend.

Amidst this highly symbolic plot, Khleifi dedicates ample screen time to the wedding and ritual celebration itself, turning his focus to the traditions at risk of disappearance and the way that the very legal fabric of Israel is designed to eradicate them.

Wedding in Galilee is available to watch on Amazon Prime.

Divine Intervention, directed by Elia Suleiman (2002)

Elia Suleiman is arguably one of the first names that come to mind when discussing Palestinian cinema, best-known for his 2002 ‘Divine Intervention,’ which cemented his status as a master of dark comedy.

The film opens onto a distraught Santa Claus being chased by a group of children through the streets of Nazareth, while toys fall out of his satchel. Elsewhere in the city, a visitor asks an Israeli policeman for directions. Unable to answer, he asks a blindfolded Palestinian detainee for help. The story unfolds in a series of equally absurd, loosely connected vignettes – all of which are observed by E.S., Suleiman’s mute on-screen alter-ego, played by the director himself.

‘Divine Intervention’ marked an important turn in Palestinian film history, for several reasons. First, in the words of Lebanese critic Rania Samara, “Before this film, the average person in the West did not know of the existence of a Palestinian cinema at all.” Second, the film’s comedic tone proved a powerful antidote to ‘media fatigue’ around the Palestinian cause, laying the ground for a rich tradition of dark comedy to emerge from the country.

Third, while it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Palme D’Or, and reaped prizes at several international festivals, ‘Divine Intervention’ was snubbed by the Academy Awards on the basis that “Palestine is not a country” – eliciting widespread international debate.

Divine Intervention is available to watch on Netflix.

Like Twenty Impossibles, directed by Annemarie Jassir (2003)

If festivals carry political significance, so do shooting locations. Nowhere is this symbolic weight more apparent than in Palestinian activist, poet, and filmmaker Annemarie Jacir’s ‘Like Twenty Impossibles.’

Co-written by Jacir and Kamran Rastegar, the seventeen-minute autobiographical mockumentary follows a young Palestinian director who has returned to the West Bank after living in the United States for several years. While shooting outside of Jerusalem, she and her film crew are stopped at a checkpoint where even her U.S. passport is no defense against the violent scrutiny of Israeli authorities.

In outlining the geography of violence in occupied Palestine, ‘Like Twenty Impossibles’ also sheds light on the obstacles to the existence of a Palestinian film industry – and the resilience of its national cinema. The film premiered at the Cannes International Film Festival, where it became the first short film from the Arab world to be chosen in the festival’s Official Selection, while Jacir became the first Palestinian woman to walk the festival’s red carpet.

Like Twenty Impossibles is available to watch on Netflix.

Paradise Now, directed by Hany Abu-Assad (2005)

If ‘Divine Intervention’ helped popularize Palestinian cinema in the West, ‘Paradise Now’ propelled it to household notoriety. Hany Abu-Assad’s film follows 27 hours in the lives of two Palestinian childhood friends, Said (Kais Nashef) and Khaled (Ali Suliman), as they prepare to carry out a suicide bombing together in Israel.

Owing to its inherently tough subject matter, ‘Paradise Now’ prompted controversy on every end of the political spectrum. Though it was never screened in Nablus, residents of the city who were able to see it criticized the film’s depiction of the suicide bombers as “less than heroic,” claiming it did the Palestinian cause a disservice. Meanwhile, Israeli viewers and some in the United States, where the film had a standard theatrical run, accused it of being “pro-terrorist.”

For all the controversy it sparked, widespread critical acclaim for the film culminated in a key victory both for Abu Assad and for Palestine. In 2006, ‘Paradise Now’ became the first Palestinian film to be nominated for an Oscar – marking the global film industry’s symbolic acknowledgement of Palestine.

Paradise Now is available to watch on Netflix.

Larissa Sansour’s Sci-Fi trilogy, (2009 – 2015)

Like most of the Arab world, Palestine is not known for fantasy films; but in the past decade, science fiction in particular has gained growing popularity in regional literature and film. London-based visual artist, photographer, and filmmaker Larissa Sansour has been one of the leading voices in this growing body of Palestinian sci-fi.

Her ‘sci-fi trilogy’ comprises the short films ‘A Space Exodus’ (2009), ‘Nation Estate’ (2012), and ‘In The Future They Ate From The Finest Porcelain’ (2015).

The first film draws its title from Stanley Kubrick’s ‘A Space Odyssey.’ Borrowing the latter’s visuals and infusing its epic musical score with Arabesque chords, ‘A Space Exodus’ shows Sansour planting a Palestinian flag on the moon, before drifting into outer space. ‘Nation Estate,’ meanwhile, takes the two-state solution to unimagined extremes: the whole of Palestine is cramped into one massive skyscraper, where each floor comprises one city.

Drawing on real incidents of antiquities fraud carried out in Israel, the third film follows a futuristic ‘narrative resistance group’ planting elaborate porcelain artifacts, which in fact belong to an entirely fictional civilisation. Their aim is to influence history and support future claims to their vanishing lands.

Together, the three films weave a narrative of Palestinian resistance, diaspora, and the grim future ahead if ideological deafness continues to be the chosen pathway of the international community. Speaking to Ibraaz in 2014, Sansour explained her choice of sci-fi as her preferred genre, saying “I take the present political situation on the ground, with the history of Palestine as a reference to what I am working on. So even though it seems that what I am doing is surreal, this parallel imagined universe that I create is firmly based on the political situation in Palestine.”

The three films comprising the sci-fi trilogy are available to watch on Amazon Prime.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (0)