Mass market art, in this day and age, is usually produced by the most powerful members of society: businessmen, entertainment industry executives, managers, and even politicians.

Those seen as ‘little people’ in society, who live and die quietly and lead ordinary lives, are often not deemed interesting enough to be featured in best-selling books and blockbuster movies by most directors and writers.

Yet, some writers know that beauty is not only found in the stories of the most heroic or extraordinary characters; that the magic of life does not need to be shown through sparkle, gold and greatness, but also through the lives of ordinary people.

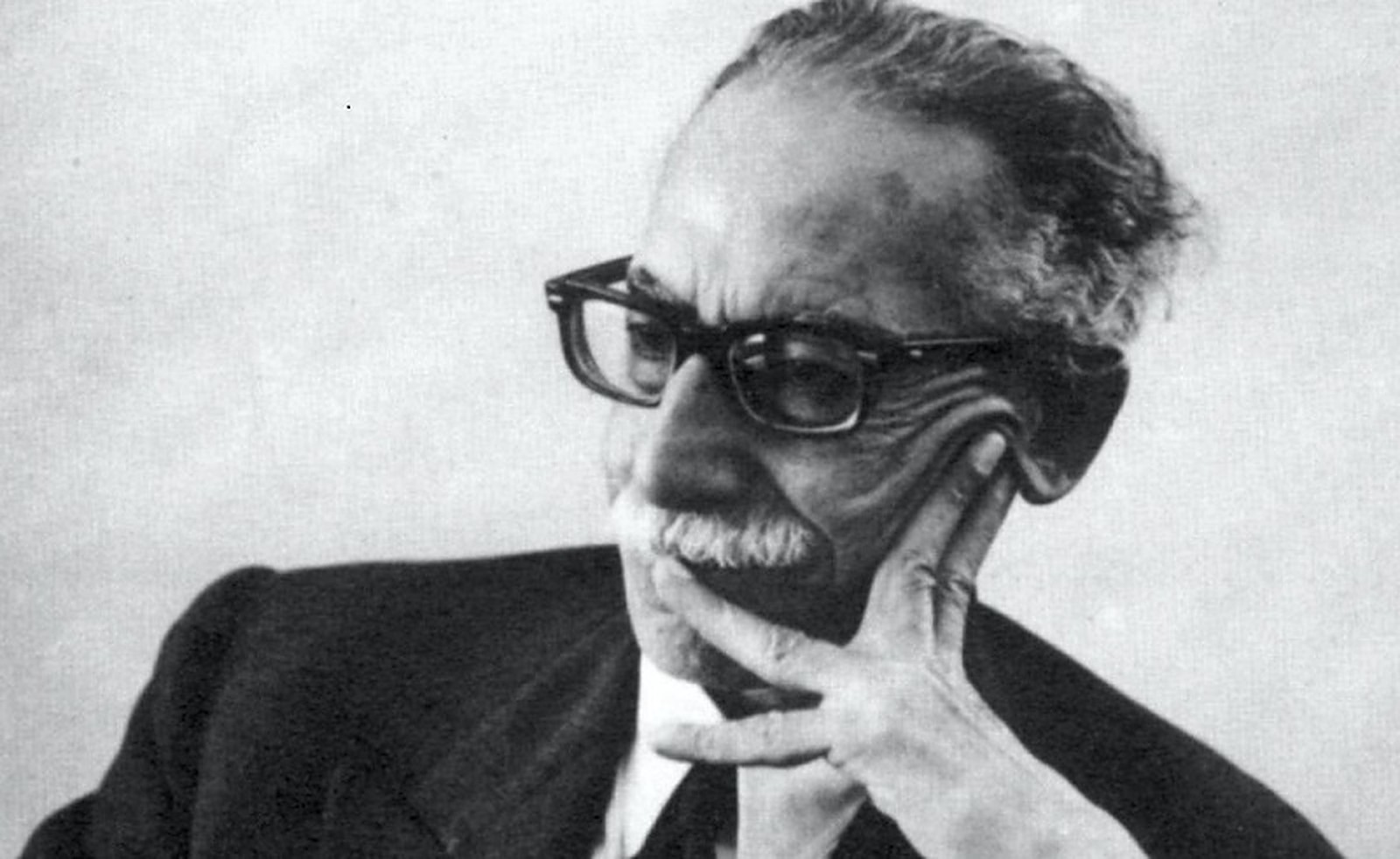

Renowned Egyptian author, Tawfiq al-Hakim, explores the quality of beauty of an Egyptian man’s life in the Maze of Justice: Diary of a Country Prosecutor (2023), which was originally published in 1937 but then translated for a new edition by Saqi Books.

The novel is a semi-autobiographical tale that tells the story of a young and ambitious prosecutor who is sent from the busy city of Cairo to a rural village in the Delta, where he is tasked to deal with major cases of crime. Though he is proudly armed with European education, the prosecutor becomes perplexed by how a foreign legal system fails to reflect and deal with the lives of the villagers, who lead a life he cannot understand. Justice, he recognizes, is seldom as straightforward as it initially appears, and is also not universal as he first thought.

Hakim zooms in on the tedious and the lustreless, the boring and the colorless. He looks at the details of an ordinary life: how the labor of a public prosecutor shaped him, how many cases he investigated, and how many reports he submitted. Each morning he woke up, each train he took, and each piece of food or clothing molded him and left its stamp on him.

Since the book is divided by chapters titled by dates, as any diary would look like, the book narrates how every single day can give or take from a character’s strength and supple grace. Even as the reader may at times feel that the chapters are too long for just one day’s worth, the intricate details of the character’s emotions and moments of complete stillness only amplifies the humanity and true beauty of his narrative.

A Complete Lack of Knowing

Although the prosecutor carries the weight of an important title, Hakim’s novel reveals that power and glory may shine from the outside, but when one looks deeper, one discovers that these powerful men can barely control the hours of their day, nor the countless paperwork and bureaucratic systems that they have to go through.

In one symbolic scene in the novel, the prosecutor argues with another official about the weight of a report, as the latter believes that it, being heavier than usual, is too long to spend on just one case.

“The murder of a human being! All in ten pages?” he exclaims, to which the prosecutor replies, “Next time, God willing, we shall be more careful about the weight!”

This scene demonstrates the mundanity and triviality of office work, and how human labor is not usually a tale of achievement and growth, as most movies portray, but of everyday struggle and shallow conflicts.

The characters in the novel are also simple-minded and frivolous, often acting in childlike ways despite the complexity of their adult lives. One character, Shaikh Asfur, depicts the mysterious persona of a highly religious figure that evokes the aura of knowing the unknown, though he is actually driven by speculation. Throughout the novel, his character juxtaposes the formality of the prosecutors and high officials, who try to analyze a murder case through reason, while he often distracts them with his theories and mantras. At one point, he warns the prosecutors against women, and tells them that women can also be ‘criminals’.

Despite Shaikh Asfur’s sense of being an all-knowing mastermind, a central theme that threads itself through the pages of this novel is the complete lack of knowing.

The phrase ‘nobody knew anything’ was repetitively mentioned, to not only symbolize the utter powerlessness of the prosecutors, but also how often bias and speculation can influence one’s decision-making. The public prosecutor becomes frustratingly confused as to why his years of education cannot explain or understand the cases he was dealing with, so much so that he begins to succumb to the speculations of Shaikh Asfur, and even speculate that there was a ‘devil’ that shot a man dead.

At the core of the novel is an important message: the limits of human endurance. No matter how many hours he works, or how much mental and physical effort he exerts, the public prosecutor mostly looks forward to tasting a morsel of food and stretching himself on bed to sleep. No matter the number of murderers, criminals, and victims, he can only truly achieve one thing: submit the report and then catch the train to go back home. Such is the greatest achievement of an ordinary person in Hakim’s novel.

Egyptian Existentialism

What intrigued me most as a reader, however, is seeing how estranged rural Egyptians were from foreign rule in the 1930s in Egypt. As Plato once argued, justice in a state can only be possible if it resides in the soul and heart of its citizens, yet for many of the prosecutor’s criminals, civil law was an alien invention, because it was deemed to be a foreign code that did not reflect cultural contexts and societal conventions.

A strong example of this is when impoverished villagers randomly come across a pool of clothes in muddy waters, and happily rush to take them and wear them. When the police officer finds them, he accuses them of thieving and takes them to the prosecution.

In the middle of a heated discussion, the public prosecutor is bewildered as to why they do not understand the illegality of their acts, to which they respond: “haven’t we suffered enough from the government? It doesn’t clothe us and doesn’t leave us free to clothe ourselves.”

In the end, Hakim’s novel brings forward an Egyptian interpretation of existentialist philosophy, and of appreciating the beauty of the ordinary. Once the prosecutor accepts the absurdity of his life and work, he learns to enjoy the little pleasures, joys and observations of daily life in rural Egypt and gives it his own meaning.

Hakim makes all other dramatic and thrilling works of the present seem insignificant by putting the prosecutor’s life under the microscope, just as a scientist examines an ant. The novel does not seek to deceive, shock, or amuse its readers; instead, Hakim portrays society’s most prevalent issues in a single narrative. It is art that genuinely investigates life the same way a scientist studies the universe.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (2)

[…] Source link […]

[…] post REVIEW l Prosecutors, Peasants, and Crime in Egypt: Tawfik al-Hakim’s Diary of a Country Prosecuto… first appeared on Egyptian […]