“Theatre is the heart of our community; it’s a legacy handed down from ancestors who were born with art in their blood.”

This is how Nubian artists articulated their deep-rooted passion, longing, and love for theatre during the recent screening of “Tyatro al-Nubia تياترو نوبة”, a documentary produced by Nubian Geographic —a Nubian initiative dedicated to preserving the heritage, history, art, and languages of the Nubian people — in collaboration with the Tandem Amwaj Collective Routes.

This event, held last month in Cairo, was the first screening event for Nubian Geographic’s documentary after their debut in Aswan.

The tears, the laughter, and the nostalgia for theatre were all weaved together in the documentary into a single, overarching emotion: the feeling of community. Watching it was like exploring an ancient monument that celebrated centuries of artistry, even though it was just a 30-minute film.

While the grandeur of monuments like the Abu Simbel temples define Nubia’s landscape, history is also etched into the stories and emotions of its people. Even after years of displacement and the destruction of public spaces like the Abu Simbel community theater, the stories of these spaces still live in the hearts of every village, and every community.

Filming the experiences of artists and actors across generations, the documentary explores the nature and meaning of public space and how its loss, exemplified by the destruction of the Abu Simbel theater, can have a lasting impact on a community, not just physically but also emotionally.

Theatre as a way of being

For ancient societies, artistic creativity was not merely an expression, but a way of being — it was a way of connecting with the environment just as one connects with friends, family, or loved ones.

Their relationship with their environment was as vital as their relationships with each other, and art served as one of the languages through which they communicated this connection.

This is why the Nubian language transcends mere words; it finds expression in music, dance, and theater. Art, which is a language unto itself, is inextricably linked to the Nubian language and identity. They are mutually dependent; one cannot exist without the other. Both the artistic language and the human language are interconnected.

One example of this connection is how Nubian traditions are deeply linked to the Nile. Their popular dance, Arageed, involves men, women and children moving in lines with steps to the right and left, while another dance performed by women mimics the movements of fish in the Nile.

Both dances represent the Nubians’ deep bond with the Nile River and their surrounding landscape, illustrating how their relationship with their environment encapsulates the essence of their culture.

Another example is community theatres, and their crucial role in preserving the Nubian language and unique forms of expression, particularly the comedic Nubian approach to life and community challenges. Even a simple community joke expressed in the theatre plays can help people collectively understand and address their challenges rather than individually.

Mazen Alaa El Din, a seventh-generation Nubian following the Aswan Dam displacement, is a producer of the Tyatro Al-Nubia تياترو نوبة documentary and a member of the Nubian Geographic team.

The idea for the Tyatro Al-Nubia تياترو نوبة documentary initially emerged from a casual discussion with friends. “During a casual conversation, someone brought up Nubian community theatre, and everyone was surprised, saying, ‘Wow, we didn’t know that.’ So, we decided to explore further, which led us to start working on the documentary about a year ago,” he tells Egyptian Streets.

Alaa El Din explains that Nubian theatre began in original Nubia around the 1920s before the displacement, addressing social issues through comedy. Ultimately, the theatre aimed to correct wrong behaviors by entertaining audiences, who could both laugh and reflect on their actions.

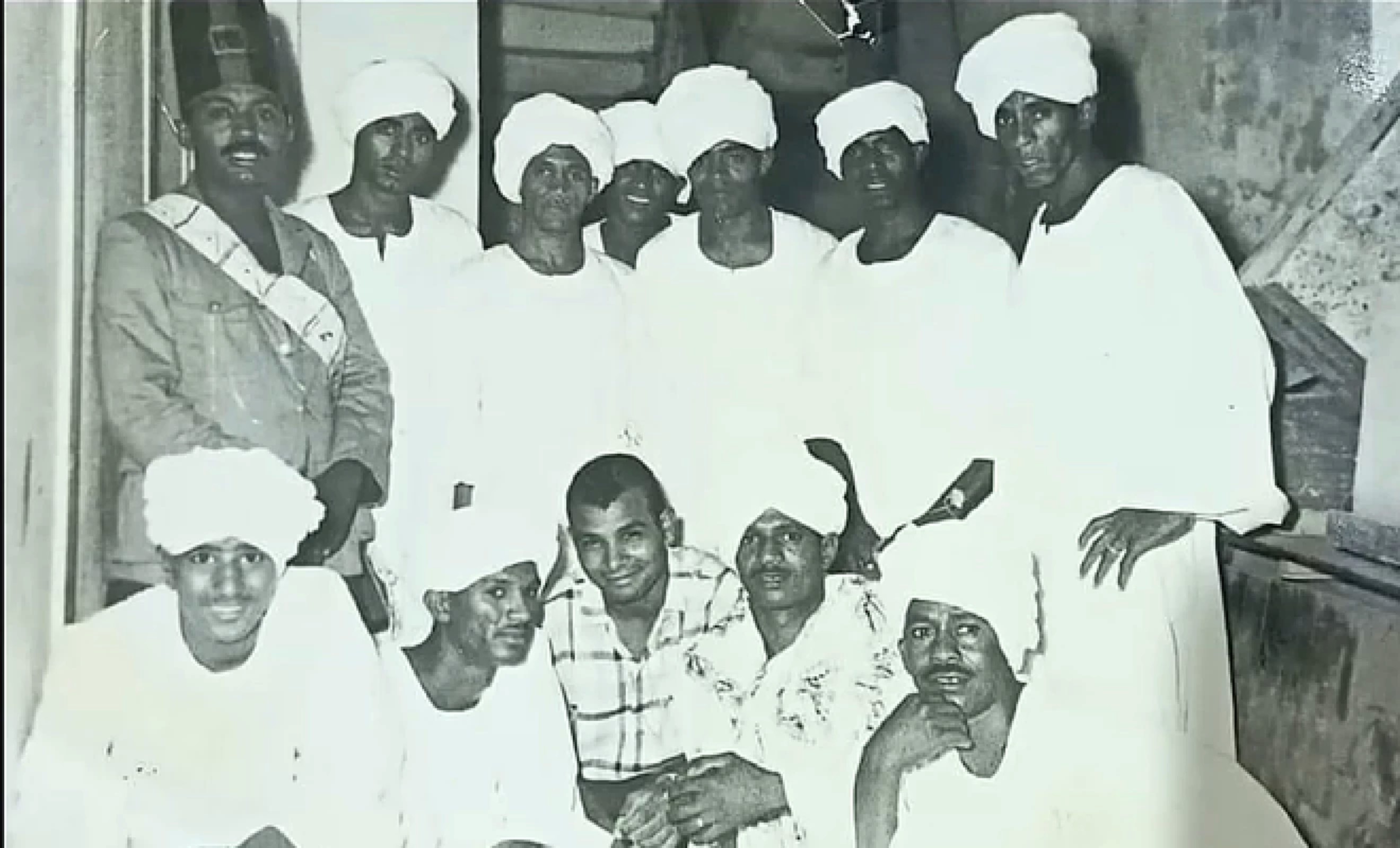

The origins of this tradition are linked to the Nubian scouts, who were regarded as the first scouts in Egypt. These scouts initiated theatrical performances in their villages, which saw audiences gathering in circles, with actors performing in the center.

“Community theater was essential in protecting the Nubian language and music. Because there isn’t any formal protection for the language, theater was used as a safeguard, allowing people to hear and explore specific words and phrases, deepening their connection to their culture,” he adds.

One of the issues addressed in their performances was corruption within the community, particularly focusing on bribery among members of parliament.

“The community theatre tackled real issues that people were hesitant to voice, using comedy to first help the audience recognize and then reflect on these problems. It usually addressed a wide range of topics, from political to social challenges,” Alaa El Din notes.

The significance of public space

The story of the Abu Simbel theatre begins and ends with the significance of public space, and the impact of public spaces in fostering community. It stands as a symbol of both cultural heritage and destruction, embodying how a single public space can encapsulate memories of both joy and sorrow.

The ancient tale begins with Ramesses II constructing the Abu Simbel temple for his wife Nefertari in her native village, as a tribute to her family and people. It was the first temple ever dedicated to a pharaoh’s wife. To adorn these grand temples, Ramesses II enlisted numerous Nubian artists, who relocated to Abu Simbel for the project and remained there.

Today, Abu Simbel is celebrated as the origin of Nubian artists, which is the central focus of the documentary.

This public space gave rise to many prominent artists, including the folklore band of Abu Simbel, and was also the site of the Abu Simbel theatre’s construction in the 1980s.

“The actors in this community may not be professionals; they are amateurs driven by a passion for acting and a desire to entertain and bring joy to others,” Alaa El Din says.

However, the destruction of this public space was not only physical but also emotional, leaving lasting wounds that continue to affect the community. In the documentary, many artists visit the public space with deep nostalgia and sorrow for what once was.

“Approximately twenty years later, the government demolished the Abu Simbel theatre to reconstruct it, but it was never rebuilt,” he notes. “Through this documentary, we aim to raise awareness about its significance and advocate for its reconstruction.”

For many, art is typically associated with large cities like Cairo, where major singers and stars achieve fame and success. Yet, in the smallest Nubian villages and throughout Egypt, numerous talented artists and singers remain unsupported and unrecognized.

“It’s time to support artists and singers from villages, not just those in big cities. These villages have a rich artistic heritage that also deserves recognition and protection.”

Comments (0)