In a cozy apartment in Maadi, the light filters inside the room where a 46-year-old cartoonist holds a pad and a digital pen, flicking color on the wings of her newest drawing. On the walls hang multiple drawings, including one of a shark threatening to eat a man alive, perhaps a symbol of the rampant poverty Egypt is facing with prices steadily growing.

Doaa El Adl has quickly become one, if not the most known of Egypt’s cartoonists.

With her uncanny ability to blend humor, wit, and profound social commentary, she has become a force to be reckoned with, captivating audiences around the world.

Born in Damietta in 1979, El Adl honed her skills by studying Fine Arts at Alexandria University. It was during her college years that she discovered her love for cartoons and comics, drawn to the medium’s unique ability to provoke thought and critique social norms. From there, she embarked on a journey to challenge conventional narratives by employing sharp satire and creativity in her artwork.

“I’ve always had opinions and perspectives; a cartoonist, by nature, has an opinion to share,” she explains with a glint of mischief in her eyes.

Unexpected pathways: from art to storytelling

El Adl’s work is characterized by a distinct style, which balances humor and thought-provoking imagery. Using vivid colors and expressive characters, she brings to life the everyday struggles and triumphs of Egyptian society. From political corruption and social inequality to gender discrimination and human rights abuses, El Adl unapologetically confronts sensitive issues head-on, offering a fresh perspective that challenges established norms she grew up to in Egyptian society.

“My childhood was between Damietta and Libya due to my father’s work,” she recalls before explaining that she then applied to study Applied Arts, specializing in decor theater and cinema in the University of Alexandria. After a short stint in decor, she entered the field of journalism.

“My father was talented in drawing but only as a hobby; he supported me in getting into applied arts,” the cartoonist explains.

“In the past, the opinion of the mass in Damietta was that women should stay in their city, there wasn’t this idea that a woman could go to another governorate to pursue her education.”

The city of Damietta, where El Adl spent many years in, is characterized by intellectuals and artists. Despite having spent many years in other cities, between Alexandria, Cairo, and growing up in Libya, she reminisces over the port city with nostalgia.

“I can tell you that Damietta is known for its furniture makers although their trade is now suffering over there. The original carvers were artists though, and during college, we learnt foundation embroidery, so I used to go stand with carpenters as they carved the decoration into the wood.”

In Damietta, these carpenters, who opened El Adl’s eyes to art and the foundation of applied arts, are called “omyagi’’; they carve motifs of plants and french style decoration with their hands and tools. El Adl explains that the majority are known to have also traveled to Italy to practice their much-coveted trade overseas.

El Adl’s impact extends far beyond Egypt’s borders. Her artwork has been exhibited in numerous galleries and museums worldwide, receiving accolades and recognition for its boldness and relevance. She has also been honored with prestigious international awards, including the 2014 International Cartoonist Award.

Tackling the taboo

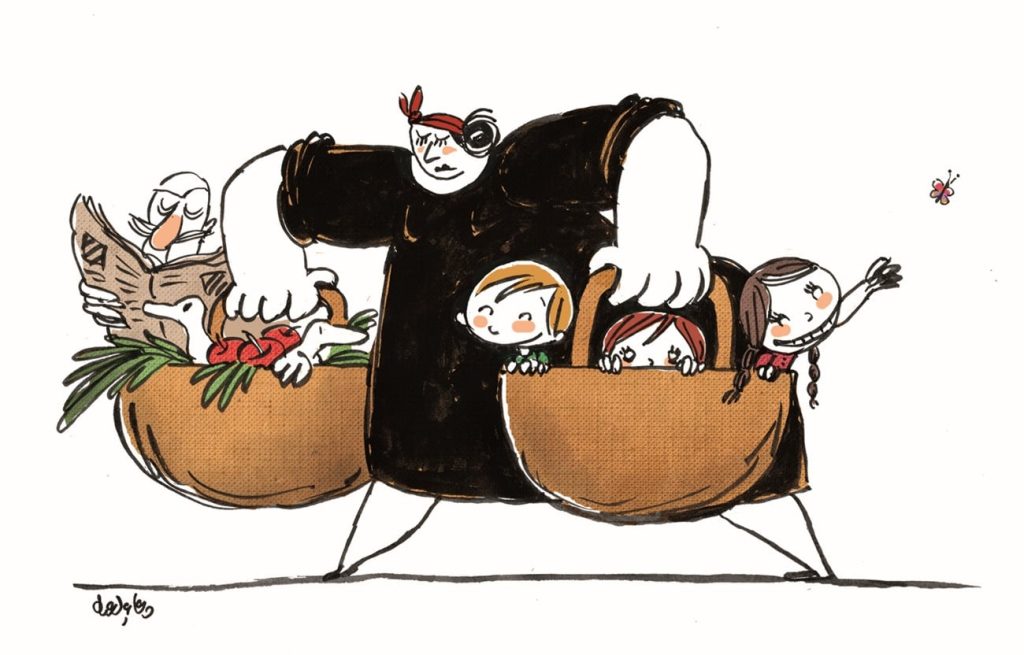

Some of El Adl’s most celebrated works feature a man’s beard silencing the mouth of a woman, a mother carrying baskets of groceries alongside her many offspring, and a man from the Gulf prancing around a trolley full of underage Arab girls, in a bid to marry them.

Through her work, El Adl tackles vulnerabilities faced by women in Egyptian society, providing a powerful symbol of resistance and empowerment.

“The topics that I like to draw are biased, some artists draw inspiration from daily events, capturing a reaction and then there are cartoonists who have their own bias and who draw topics related to their everyday work,” she says.

As for the topics she is most passionate about: “the people we don’t see on television, whom the lights are never cast on, who don’t look good or who are not too rich, the workers, the poor, those of the middle class who are slowly disappearing and who I consider myself part of, women until they get their rights – because women are no angels all the time but they deserve their rights – children, for example, as laws still don’t protect them from familial abuse.”

Besides her artistic prowess, El Adl is also a vocal advocate for freedom of expression and the role of cartoons in political discourse. Her courage to confront controversial topics and challenge established authorities has made her an icon of the resistance movement in Egypt.

Yet, her boldness does not go unchallenged.

“The first people who have criticized me for my work were my colleagues,” she says with a smile, recognizing that she depicts, in art, more women than men, and the latter often in a poor light. Nonetheless, she is proud of her capacity to spark up a debate, which she deems healthy and necessary in the modern day global context.

“I remember when I first started drawing men: I used to portray some of them with a bellydance strap, dancing. My colleagues were upset, but then they accepted this. Still, after my book ‘50 drawings’, I did an exhibition which was attended by both men and women. Some women cried because they related to the content, and sometimes men saw this as an exaggeration, not a reflection of reality.’’

The illusion of freedom of expression?

For years now, freedom of expression has been contested in Egypt.

The country, which is undergoing severe economic crises, finds itself in a sensitive socio-political context where criticism of governmental decisions can be perceived in a negative light, particularly by governmental figures. Apart from Iran, the Middle East and North Africa still have Egypt and Saudi Arabia among the top 10 countries in the world for the imprisonment of journalists, according to a 2022 report by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Doaa El Adl is no stranger to the challenges of press and freedom of artistic expression.

“Every day is a struggle: to maintain your values and stick by your judgment. You have to convey the meaning in a different way, while before we [cartoonists] used to draw in an explicit and direct manner, now you have to be more patient and exert more effort to convey the same message in a calmer way,’’ El Adl explains.

“If the artists succumb to the red lines [explicit boundaries of art] then there won’t be the art of caricature in Egypt or in the world,’’ she starts before adding that the “idea of complete freedom is an illusion.”

Emboldened and feeling a strong sense of kinship with other cartoonists worldwide, she starts to list examples of artists in the USA, Canada, Mexico and Israel who have been let go from their jobs because of drawings that have criticized governments or public figures, such as Michael de Adder who etched a cartoon showing Trump in the face of the migrant crisis in North America, or António Moreira Antunes’s cartoon which stirred controversy for its alleged use of anti semitic tropes and depiction of Prime Minister Netanyahu.

‘’It’s delusional to say only the Middle East has issues with freedom of expression,’’ she affirms.

‘’There are many instances that prove that the world does not like cartoonists, and of course among them is the Charlie Hebdo attack.”

When asked whether cartoonists should be held accountable for their content, El Adl lets out a resounding and firm negative.

‘’It’s the nature of the art, societies that are prone to distortion are the ones that refuse a different point of view and freedom,” she explains.

In the 2003 essay “Political Cartoons: Now You See Them!” by Rhonda Walker, the author highlights the inevitable political nature of cartoons: not only are they a quick, democratic segway into the minds of the masses – no matter the ethnicity, class or gender – they also blend the ‘equalizing’ aspect of humor with ‘simple complexity.’ Cartoons can make us laugh, cry, or shock us to the core. They can elicit thoughts and reactions out of us, or tap into what we find relevant to our everyday lives. They pack a metaphorical punch.

“I think that a cartoonist who aspires to change the world through his art will suffer greatly, art alone is not capable of eliciting change, but art can document events that historians themselves can lie about and politicians would color differently, and media would manipulate, but a true cartoonist, if he or she is intent on drawing things as they are, then he or she is documenting an event or a period of time,” El Adl says “You can read the history of a country through caricatures, if the cartoonist is honest.’’

For the most part, deriving content and inspiration for cartoons relies heavily on current events and trends.

“A political cartoonist observes how the world is developing […] Everything is very connected, the issue of the dollar in the USA, won’t that bring about a world crisis in a short amount of time? Politics isn’t only looking at price changes in Egypt, it’s having a perspective on how the whole world is evolving,” El Adl says.

In and for the future

‘’I hope I never get to a point where I stop evolving in my art and in my lines,” she shares frankly.

El Adl has positioned herself as a seasoned cartoonist, with decades of experience in the industry. She is often amused when Facebook shows her a drawing from over a decade ago, as the drawings are often “full of naivety and a lack of craftsmanship.”

Nonetheless, she is refreshingly candid about her desire to evolve and grow, especially considering there are very few women in Egypt excelling in the same field. The few she knew had taken on the path but they abandoned it – not because they lacked the talent but because the journalistic environment in which they tried to carve a career for themselves was discouraging.

The artist, who has worked at Egyptian news outlet Al Masry Al Youm since 2009, is an avid consumer of cartoons herself. Her repertoire of inspiration includes cartoonists Waleed Taher, Makhlou’, Mohie El Din El Labad, and Egyptian cartoons from 1960-1970s.

These days, she has transitioned from paper to a digital pad – as most modern artists have. And along with the shift to her pad and stylus, so have her thoughts and themes undergone waves of transformation.

She bravely takes on the Sudan crisis, resistance in Palestine, as well as climate change.

“We’ve all started to feel how the summers have been getting warmer, and the winters colder. I realized countries were undergoing calamities due to the floods and so on. We are all feeling the effects of climate change worldwide, it’s not some fabrication,” she explains.

“We will never wake up to world peace,”El Adl divulges, with a hint of laughter.

But there is also hope dripping from her voice, as she enthuses about the beauty of cartoons and how they can be understood by all minds worldwide.

When asked if she feels more like a cartoonist or a journalist, she says ‘’I’m a cartoonist of course, there’s a difference between them both. Evidently, they both have to rely on research to produce an output, but a journalist writes an article of 100 words to convey a meaningful message, a cartoonist does it in one frame.”

In a region marked by political upheaval and social unrest, Doaa El Adl’s cartoons have served as a beacon of hope and catalyst for change. By amplifying the voices of the marginalized and shedding light on the plights of the oppressed, she has forever etched herself in the annals of powerful and impactful cartoonists.

Comments (0)