When Ziad Rahbani, the legendary Lebanese composer and pianist, first tried to describe his music, he told the Los Angeles Times in 1988 that it was “something like a hamburger that tastes of falafel”, a nod to the beloved Arab street snack made from spiced chickpeas or fava beans.

What he was trying to say is that the popularity of globalized Western music during his time, symbolized by the hamburger, only scratches the surface of his music. But when you truly pause and listen, taking in each note and chorus, the depth and texture of the falafel slowly comes through, until it no longer feels like it was ever a hamburger.

The timing of the interview, and Rahbani’s choice to use the hamburger metaphor, could not have been more fitting. It is almost as if he had predicted where the global music industry was heading, which was toward a hamburger-like sound that was globalized, short, and stripped of any distinct cultural identity. It was also just a few years before the 1990s, when songs started becoming shorter and simpler, with many hits barely passing the three-minute mark.

Record labels and radio stations were hungry for hamburgers; snacks that were short and digestible. And short and digestible is exactly what he gave them, with Kifak Inta (How Are You, 1988), produced in the late ’80s and later released on cassette and CD in 1991. He had an instinct for reading the moment, sensing where things were headed. Instead of diving in headfirst, he only dipped his toes in the water, testing the trend, all while keeping his roots intact and his sound grounded in tradition.

From the very first few seconds of the song, especially with the iconic opening piano notes, heavy with the same shade of melancholy that is found in a Western jazz or blues tune, it is clear that this is a short and sweet melody. It carries that same cinematic pull one would find in a Frank Sinatra song from a classic romantic comedy, the kind that makes me imagine myself sitting down on a balcony somewhere, drink in hand, melting into the beauty of the moment.

No matter the chaos, the tears, or whatever tragedy my mind has been holding onto, the melody steps in like it has just redecorated my entire headspace with fresh and new furniture. The furniture feels vintage, almost antique, and suddenly my mind takes on the same warmth my grandmother’s house once held, an old, familiar warmth that is nearly impossible to find anymore.

And just as I find myself sinking into memories of my grandmother’s house, the song shifts, and the poetic depth of the Arabic language begins to rise to the surface. This is the moment when the hamburger takes on the full texture and flavor of the falafel. The melodic phrases of Kifak Inta are grounded in the maqam system, a system of melodic scales that defines much of Arabic music, known for its fluid, wavy sound that slips between notes in a way that most other musical traditions do not.

It almost feels as though he is speaking to a wider audience, tapping into an emotion deeply familiar across the Arab world: that lingering sense of estrangement after years spent abroad, fleeing war and chasing stability, yet always carrying the ache to return, just to check in on the people you left behind.

So many parents, so many children, so many friends and families have either been forced — or have chosen, of their own will — to leave their home countries in the Arab World, driven by the instability that has weighed on the region for years. In the process, so many people have grown apart.

A conversation that never ends

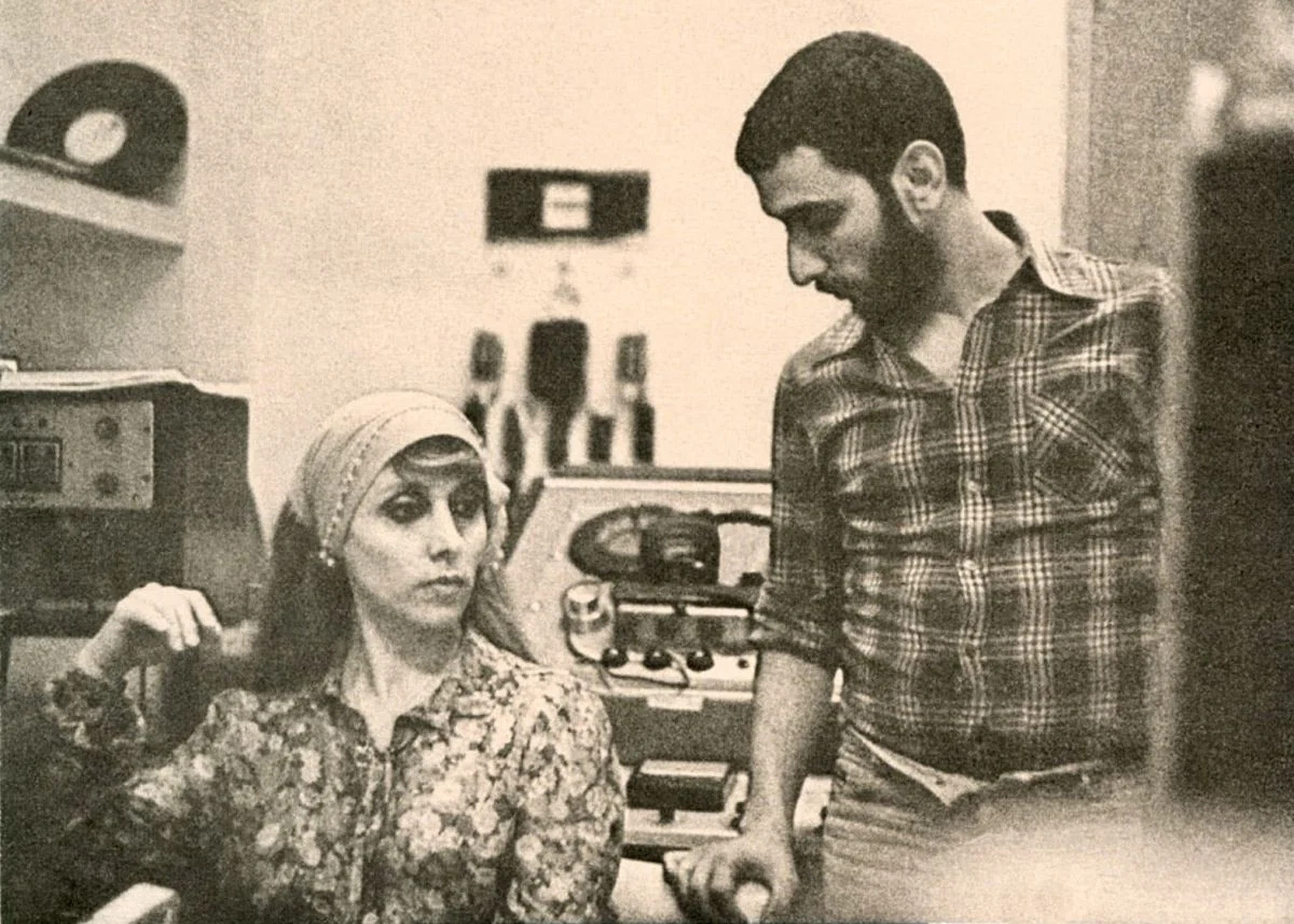

The story behind the song is one that rings true for so many Arab families living in the diaspora. As Rahbani tells it, he and his mother had not spoken in years after he moved abroad and got married. Then one day, their paths crossed. She looked at him, paused, and asked simply, “Kifak?” How are you? “They say you have kids now?” The distance grew so vast that even major life events, like having children, felt completely out of reach.

That brief moment — so simple, yet so poetic and cinematic — stayed with him. He went home, sat at his piano, and out of that memory alone, the entire song was born.

Much like a novel or a play, the song unfolds as if I am a character in a story that Rahbani is writing into existence. As Fairuz’s otherworldly, ethereal voice enters the setting, I turn around and hear her speaking, asking, almost in a whisper, “Do you remember the last time I saw you that year?” Then, after a pause, another question follows, just as tenderly: “Do you remember the last word you said?”

To listen to Fairuz is one thing, but to feel as though you are in an intimate conversation with her, where every word is imbued with warmth and emotion, is something else entirely. As a playwright himself, Rahbani was no stranger to crafting dialogue and building characters, but in this song, the dialogue feels bigger than just a conversation.

Rahbani was known for writing and composing songs that spoke to the real, lived moments everyone has felt at some point. Whether in a single line or an entire play, he had a way of capturing what so many people feel, his words unfolding like an umbrella that stretches wide enough to cover the whole world in its emotion.

For a brief moment, it feels like the entire world is living under the shelter of his thoughts, feeling and remembering the ache of missing someone so deeply, after years of distance and silence.

Conversations often begin and end, but for Arabs, we have a cultural quirk that is unique to our language and our way of speech, as even just a single question, such as “kifak inta” can hold many meanings and carry a conversation for hours. The way we understand “kifak inta” is that we are not just asking how someone is feeling or doing, but in a way, we are also asking about their entire life, and maybe even how they feel about us too.

Kifak Inta is the embodiment of how many Arabs speak and communicate, and our love for endless conversations and asking the same question over and over, always hoping for a longer, deeper answer.

Listening to this song today, especially in the wake of Rahbani’s passing last month, has never felt more relevant. In a time when people are no longer just separated by borders, but also by screens, apps, and the blur of busy lives, when friends and families rarely have a moment to truly connect, Rahbani’s song pulls us into his world of tender emotion.

It is a song that reminds us that even the simplest conversation can become the most powerful thing there is, the one thing that still feels human in a world that has grown increasingly distant, fast, and artificial.

Comments (0)